The Zax of X

It's always fun seeing the turn

Top Comment

Brad wants to be like Palantir:

Mike, what advice would you give to a public company executive if they wanted to take advantage of passive market dynamics to make their share price go up as much as possible? Is it essentially to get your stock to be included into the largest indexes like the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100 and to smash the share buyback button as much as possible? Should a company borrow as much as possible to buy back as many shares as possible? I assume that this strategy really only works when the indexes have net inflows like they do currently.

MWG responds:

The “easy” answer is to do what Palantir did. The hard answer is tied to the work of Michael Jensen (h/t Cliff Asness):

I define and analyze the agency costs of overvalued equity. They explain the dramatic increase in corporate scandals and value destruction in the last five years; costs that have totaled hundreds of billions of dollars. When a firm's equity becomes substantially overvalued it sets in motion a set of organizational forces that are extremely difficult to manage - forces that almost inevitably lead to destruction of part or all of the core value of the firm. WorldCom, Enron, Nortel, and eToys are only a few examples of what can happen when these forces go unmanaged. Because we currently have no simple solutions to the agency costs of overvalued equity this is a promising area for future research.

The first step in managing these forces lies in understanding the incongruous proposition that managers should not let their stock price get too high. By too high I mean a level at which management will be unable to deliver the performance required to support the market's valuation. Once a firm's stock price becomes substantially overvalued managers who wish to eliminate it are faced with disappointing the capital markets. This value resetting (what I call the elimination of overvaluation) is not value destruction because the overvaluation would disappear anyway. The resulting stock price decline will generate substantial pain for shareholders, board members, managers and employees, and this makes it difficult for managers and boards to short circuit the forces leading to value destruction. And when boards and managers choose to defend the overvaluation they end up destroying part or all of the core value of the firm. — Jensen 2004

Unfortunately, this is our future. When companies like NVDA, PLTR, GE, YHOO, etc, become focused on maintaining and justifying their current stock price, it inevitably leads to poor decision-making and often outright fraud. We celebrate stock buybacks even as we acknowledge they are value-destroying when done above fair value. We simultaneously acknowledge the “wasted” resources employed in DEI initiatives at various Silicon Valley behemoths while arguing “these are the greatest companies in history!” While these are great companies, they are being hollowed out by fear of taking actual actions that would generate shareholder value BECAUSE their stock prices are too high. SMCI and Enron are simply two peas of the same (not literally) pod, separated by decades.

So, to answer your question directly — “this is NOT a game companies SHOULD be playing.” But they are and Palantir and Microstrategy are the “models.” Good luck.

The Main Event

One day, making tracks in the prairie of X, came a North-Going Zax and a South-Going Zax. And it happened that both of them came to a place where they bumped. There they stood. Foot to foot. Face to face.

“Look here, now!” the North-Going Zax said, “I say! You are blocking my path. You are right in my way. I’m a North-Going Zax and I always go north. Get out of my way, now, and let me go forth!” “Who’s in whose way?” snapped the South-Going Zax. “I always go south, making south-going tracks. So you’re in MY way! And I ask you to move and let me go south in my south-going groove.” Then the North-Going Zax puffed his chest up with pride. “I never,” he said, “take a step to one side. And I’ll prove to you that I won’t change my ways if I have to keep standing here fifty-nine days!” “And I’ll prove to YOU,” yelled the South-Going Zax, “That I can stand here in the prairie of X for fifty-nine years! For I live by a rule That I learned as a boy back in South-Going School. Never budge! That’s my rule. Never budge in the least! Not an inch to the west! Not an inch to the east! I’ll stay here, not budging! I can and I will if it makes you and me and the whole world stand still!”

Well… Of course the world didn’t stand still. The world grew. In a couple of years, the new highway came through

And they built it right over those two stubborn Zax

And left them there, standing un-budged in their tracks.

But then they tried talking…

And maybe, just maybe it’s the start of good things…

My vitriolic arguments with Cliff Asness have temporarily come to an end. He was exceptionally kind in a recent podcast appearance on The Compound, and I genuinely appreciate his new interest in my work. Very few in the finance (or is it FINance?) industry carry the gravitas to get regulators to consider standing against Vanguard and the shift to passive seriously. I consider Cliff to be one of them. I certainly am not the best choice.

Cliff and I continue to disagree, although he has come MUCH closer to my point-of-view (and will eventually come the whole way). As he notes in the podcast, when we spoke in person, he said, “Dude, you’re mad that I made it one of my three reasons instead of the sole reason.” He is referring to his recent paper, “The Less Efficient Market Hypothesis” where he proposes three mechanisms for his observation that markets may have become less efficient:

Hypothesis #1 – Indexing Has Ruined the Market

Hypothesis #2 – Very Low Interest Rates for a Very Long Period

Hypothesis #3 – We Have the Effect of Technology Backwards

As I noted in my review of his paper, “The correct answer is important because we agree that inefficient markets undermine capitalism by distorting price signals that allocate resources.” We disagree precisely because the “Why?” matters for “How do we fix it?” As Cliff notes, it’s not just enough to say there’s something wrong with something — you have to say “What to do instead.” Suppose, as Cliff proposes, the answer is that the effect of social media has made the “Wisdom of Crowds” breakdown:

The idea of the wisdom of crowds is well known. In a real sense, any decently efficient market relies on it. But having a wise crowd in turn relies on the members of the crowd being largely independent of each other. For those of a certain age, think about Regis Philbin and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” Of the lifelines in the game, the best one was always “poll the crowd.” You see, the crowd was basically kept in isolation, and even if only a small fraction of them knew the answer, the errors cancelled out and the right answer bubbled up. But what if the crowd isn’t independent, but acts in unison? Well, this has the potential not just to destroy the magical crowd wisdom but to turn it into a negative — Asness 2024

I put it back to Cliff, “What do you do about it?” Cliff’s answer (in the paper), unfortunately, is “nothing — just learn harder.” Once again, to his credit, he acknowledges that this is weakest section of the paper:

I am aware that this is the weakest section of this piece. The task is not easy and the advice is straightforward not any new genius! But perfection is never the goal and one can get better, perhaps much better, and hopefully these ideas help.

As I point out, Cliff’s mechanism for the “Wisdom of the Crowds” breaking is actually why I believe passive investing is the cause:

“The missing mechanism for Cliff’s proposal is “endowment” — it would not be enough for social media to have steered everyone except for Cliff wrong, they would need enough money (capital) to affect prices in this universal way. For some odd reason, Cliff ignores the obvious mechanism of retirement assets directed into passive indexing, specifically target date funds, in favor of near-penniless hoi polloi:”

The failure to appreciate the “coordination” that occurs when “uninformed” investors direct their assets to “passive” funds is unsurprising. The academic literature perpetuates this misunderstanding when they construct models in which there is a “single risky asset.” This is the mistake made by Davidson Heath, whose 2017 paper is often cited as a counter to my work:

It’s remarkable to make that conclusion given the same authors find (in the same paper):

“We then examine whether index investing affects investor behavior and stock price dynamics. We find that it does: more index investing causes stocks to have (i) higher share turnover, (ii) higher short interest, and (iii) higher correlation with index price movements. We also find that more index investing is associated with higher volatility”

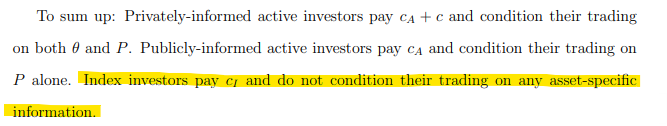

But the reason why they find this is because their model is flawed:

Key insight? “Single risky asset” — because that then allows the following statement:

This is simply wrong. “Index investors” don’t exist except as holders of PORTFOLIOS of multiple risky assets HELD IN PROPORTION TO THEIR MARKET CAPITALIZATIONS. Market capitalizations, by definition, are asset-specific information.

I was fortunate to connect with Davidson this week. I’ll spoil the surprise — after reviewing my critiques of his methodology and my work on passive, Davidson has flipped his view and acknowledges that he and his co-authors are wrong. Another small victory.

Back to The Compound podcast, Cliff did a reasonable job of summarizing my position on “what to do,” but I’ll add a few clarifying points.