The Thermodynamic Margin Call

Why Wall Street is Long the Wrong Singularity

My apologies for the one week gap. Occasionally, the attic receives an inflow of new information that requires additional reorganizing. And this is why I love writing on Substack. In response to my scarcity posts, I received a research package from Hudson Bay Capital that perfectly crystallizes the “Optimism” narrative currently sweeping Wall Street. The papers, titled “Tech Trumps Tariffs” (Nouriel Roubini) and “No, Stocks Aren’t in a Valuation Bubble” (Jason Cuttler), are sophisticated, compelling, and arguably the most dangerous documents I have read this year. Please read them.

Their argument is the highest-conviction version of the “Soft Landing” consensus. They posit that we are on the precipice of a “positive supply shock” driven by AI that will raise US potential GDP growth to 4%, crush inflation, and justify an S&P 500 target of 9,000. Their thesis is elegant: Technology (AI) enables us to dematerialize growth, rendering physical constraints such as labor shortages and tariffs irrelevant.

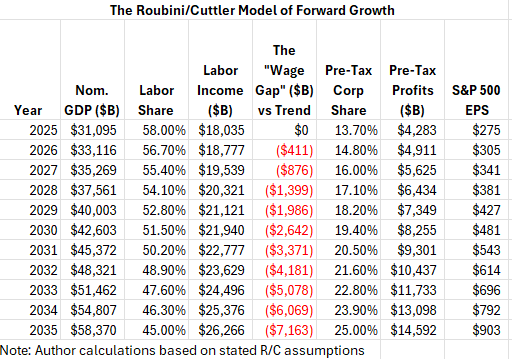

It is a beautiful theory. Unfortunately, it violates the laws of physics — specifically, the physics of our infrastructure networks. And, as the latest research from Jones and Tonetti identifies, it violates the “laws” of economics. Using their projections, it also assumes a catastrophic path for wages vs capital that will not be tolerated:

Fortunately, it will not come to pass. The Hudson Bay thesis rests on a fatal accounting error. It assumes that Machine Labor is infrastructurally equivalent to Human Labor. It assumes that replacing a worker with an AI agent is a 1:1 swap in the economic ledger.

It is not. Per-capita productivity equals throughput divided by population only if capital scales at least proportionally with the population. Wall Street assumes the numerator (throughput) scales infinitely, while ignoring that the denominator (capital stock) is physically capped. This isn’t a Malthusian tale of inevitable collapse—I’m not predicting an endpoint where growth hits zero forever. It’s about the path: the short-run thermodynamic penalties and ergodicity errors that Wall Street’s linear models miss, turning a ‘productivity boom’ into a margin call unless we adapt.

I spent the last week auditing the energy books, and the results are stark. We are not facing a “Productivity Boom”; we are facing a “Thermodynamic Margin Call”. The transition from a human-led economy to a machine-led economy carries a specific topology penalty that Wall Street’s linear models are missing.

This is the Growth Wedge. And it implies that the “Cost of Capital” isn’t going back to zero—it’s going to track the cost of rebuilding the entire US energy grid from scratch.

The Optimist’s Delusion

To understand why the consensus is wrong, we must first steelman their argument. Hudson Bay posits that US exceptionalism is strengthening. They argue that the productivity gains from AI (estimated at 0.5–1.5% annually) will outweigh the stagflationary drag of protectionism.

In their model, AI acts as a deflationary force. By substituting capital (software/compute) for labor, we lower unit costs and expand margins. This justifies a “Sentiment Spread”—a premium valuation multiple—similar to the 1985-2001 period.

The mistake in the AI-optimist model is treating machine substitution as “Hicks-neutral” (a technological change that doesn’t alter the ratio of capital to labor). In reality, this transition is energy-biased and capital-deepening.

The Ergodicity Error

More fundamentally, the AI-optimist model commits an ergodicity error: it confuses the ensemble average with the time average.

Wall Street implicitly assumes that because capital can flow and equilibrate in the long run, it will do so smoothly over the short run. But we do not live in an ensemble of possible economies. We live in a single, path-dependent timeline.

If the copper wires, transformers, and gas turbines cannot be built fast enough to support the AI load in 2027, the system breaks long before it ever reaches the hypothetical 2035 equilibrium.

They see “The Cloud” as a place where value scales infinitely with near-zero friction. But “The Cloud” is not a place. It is a physical infrastructure of aluminum, copper, and megawatts. And unlike the software boom of the 1990s, which ran on the “stranded capacity” of office buildings and efficiency gains from the death of the incandescent bulb, this new boom requires Net New Industrial Capacity (a replay of the DotCom fiber buildout).

Revisionist History: The Decoupling of Throughput

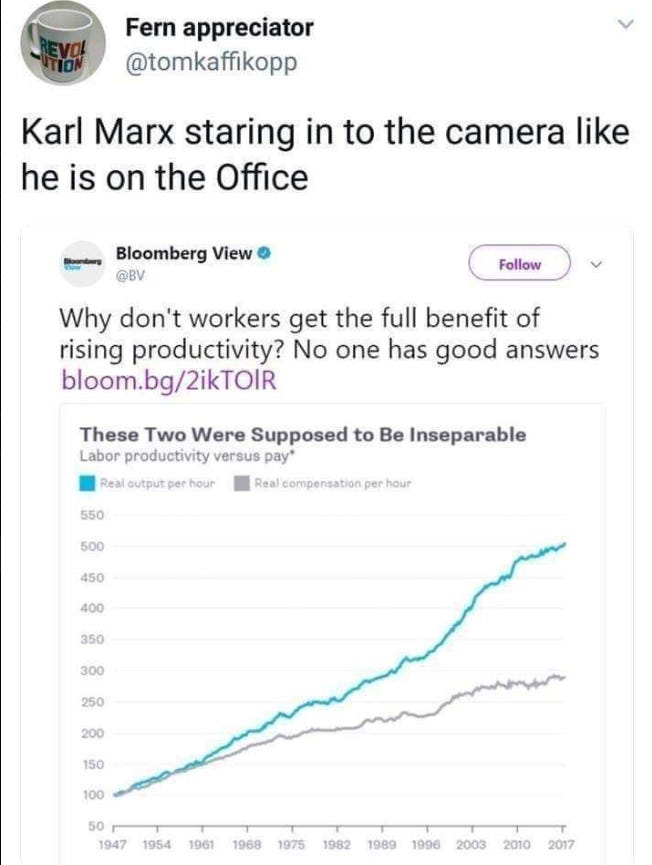

To understand the trap we are in, we have to rewrite the history of the last 50 years. Standard economics holds that the divergence between Productivity and Wages that began in 1973 was a policy failure or the result of corporate greed, the loss of unions, etc.

Institutions and policy certainly shaped how this divergence manifested, but it became unavoidable once throughput migrated from human bodies to owned infrastructure.

Some economists argue that this divergence is a statistical illusion—that if you adjust for inflation correctly (using output prices instead of consumer prices) and include non-wage benefits, pay actually kept up with productivity.

They are missing the point (unsurprisingly). The divergence isn’t a measurement error; it is a Topology Shift.

As the chart above illustrates, Labor and Productivity marched in lockstep for the first half of the 20th century. Why? Because the economy ran on Liquid Fuels and Human Labor. To burn more oil, you needed more men to drive the trucks, man the rigs, and work the assembly lines. Labor controlled the throughput and hence negotiated its proportionate share. In the areas of the economy where this remained true, as the linked paper demonstrates, wages largely tracked productivity:

In 1973, we hit the Thermodynamic Wall. We couldn’t just add more men to burn more oil. We switched to the “Cheat Code” (Offshoring) and began the slow transition to the “Electro-Capital” grid.

The reason “Consumer Prices” (what workers buy) rose faster than “Output Prices” (what workers make)—creating the statistical gap economists struggle to “correct” away—is Global Arbitrage. We used foreign labor to suppress the price of tradable goods (TVs, Toys), but we could not suppress the thermodynamic cost of living (Housing, Energy, Healthcare) in the domestic economy.

Whether you call it the end of the “Family Wage” (Sociology) or the end of “Cheap Oil” (Physics), the result is the same: The Surplus Evaporated.

The Bottleneck Arbitrage:

Pre-1973: Energy flowed through human bodies (food/transport). Labor captured the gains because Labor was the transmission mechanism.

Post-1973: Energy began to flow through increasingly privately-owned infrastructure (wires, pipelines, servers). Capital captured the gains because Capital owned the bottleneck.

The “China Shock” and automation were just accelerators of this trend. But the system didn’t totally bypass the human. Ironically, it increasingly consumed their LEISURE as data inputs to the machine.

We didn’t stop working; we just stopped getting paid. We entered a Barter Economy: we trade our “Audience Services” (attention/labor) for “Media Services” (content). The value of this labor is captured in GDP as Advertising Services (Corporate Revenue), but it is absent from Wages (Household Income). We lost the paycheck, kept the work, and called it “content.”

The Global Cheat Code

This wasn’t just an American phenomenon. The entire developed world spent the last 50 years playing a game of thermodynamic arbitrage to avoid the cost of domestic energy production.

The UK Model: When the UK hit the wall in 1976, they didn’t solve it with efficiency; they solved it with geology (North Sea Oil). When that ran out in 2000, they swapped cheap oil for cheap imported labor.

The EU Model: Europe combined cheap energy (Russia gas) with successive waves of labor arbitrage. The first phase absorbed high-skill Eastern European labor following EU expansion, effectively delaying automation. As wage convergence and demographic decline closed that channel, Europe substituted quantity for quality via non-EU migration. This preserved headcount but diluted capital per worker, intensifying pressure on housing, infrastructure, and long-standing social norms. The model’s instability reflects the same Hicks-neutral error seen in AI optimism: assuming labor inflows can substitute indefinitely for capital formation.

The East Asian Model: The “China Shock” wasn’t an isolated event; it was the last gasp of a 50-year strategy to outsource the world’s entropy to a manufacturing sink.

This becomes apparent when we consider the arbitrage that existed in 1990 that allowed the US (and other developed nations, but mostly the US) to outsource human labor:

The crisis today is that all three Cheat Codes are failing simultaneously.

The China Valve: Closed by geopolitics and demographics.

The Russia Valve: Closed by war.

The Migration Valve: Closing due to a Physical Capital Crisis.

The Hicks-Neutral Fallacy of Migration

Just as Wall Street treats AI projections as having access to infinite energy, policymakers treat migration as having infinite infrastructure. The standard assumption was that migrants moving from capital-poor to capital-rich regions would “level up” to Western productivity.

This is not a claim about migration per se. In a capital-abundant regime that builds housing and infrastructure at scale, migration is productivity-enhancing. The failure arises only when policymakers assume Hicks-neutrality and refuse to build. Migration stress arises not from flows per se, but from the slow-moving stock of housing and infrastructure.

If Physical Capital (Housing, Healthcare, Roads, Schools) is constrained, adding more people doesn’t raise the migrant; it levels down the native and forces them to compete (via higher prices) for these increasingly scarce resources. When the capital stock per capita dilutes, the “B-Sector” (Housing/Services) experiences massive inflation. The political backlash closing borders today isn’t just cultural; it is a reaction to the thermodynamic crowding out of the native working class.

The Energy Investment Equation

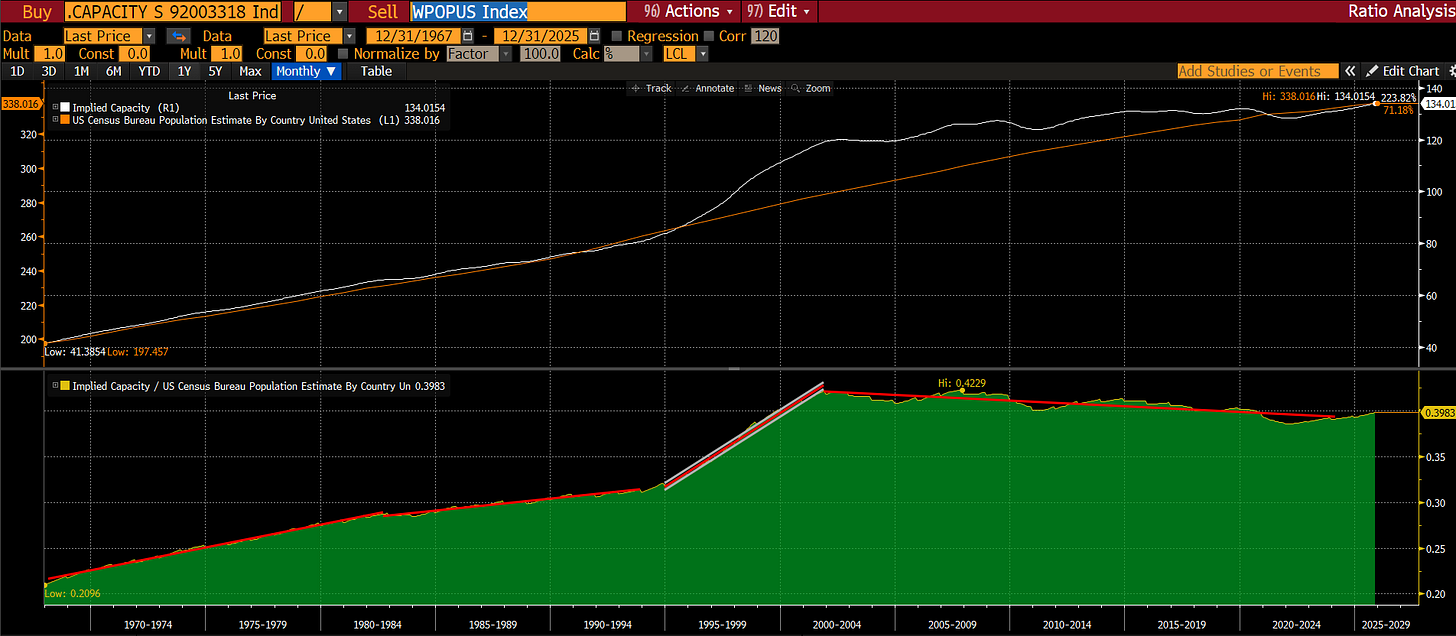

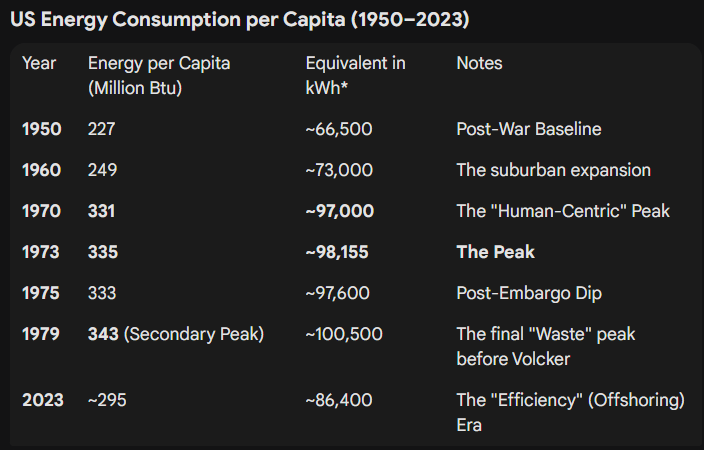

The end of the “Cheat Code” is visible in the raw physical data.

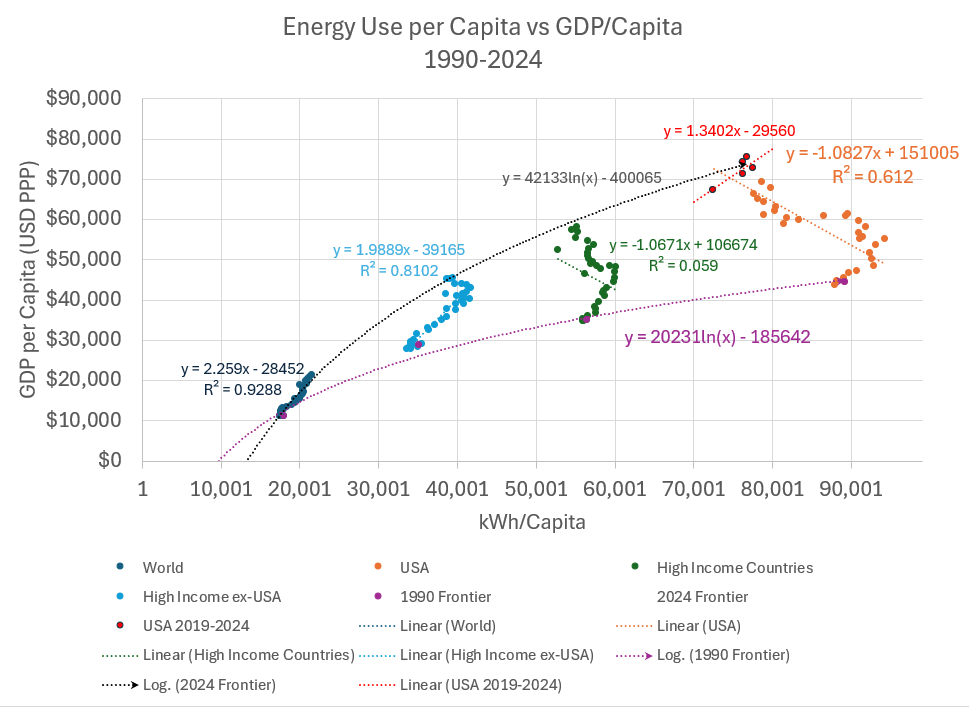

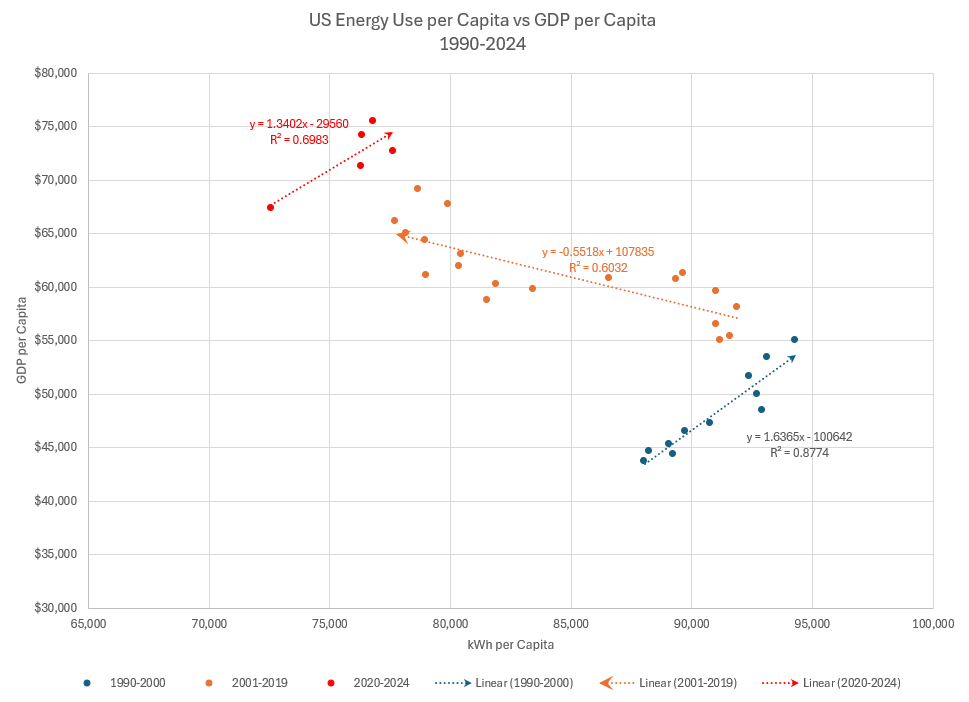

For twenty years (2000–2019), the US economy pulled off a magic trick. We grew GDP while keeping energy consumption flat. This was the “Negative Slope” anomaly.

That illusion is over.

Since 2020, the US slope has turned positive (Beta = 1.34). To generate the next dollar of GDP, we must once again use more energy. Why? Because “US Exceptionalism” now includes Reshoring. We are bringing aluminum smelting, chip fabs, and data centers back home.

The “14% Bottleneck”

Here is where the math gets violent. The core of the Bull Case is that AI will “fill the gap” left by a stagnating labor force and efficiency will lower overall usage.

But let’s look at the topology of that thesis.

You can’t efficiency your way out of a shortage.

The US primary energy system consumes roughly 100 Quads (29,000 TWh) of energy per year. However, the electrical grid only generates ~4,200 TWh.

The Reality: The grid handles only ~14% of the nation’s energy flow.

The Rest: The other 86% flows through liquid fuels (oil/gas) and direct chemical inputs (food/fertilizer).

The Human Engine (Distributed & Diversified)

Humans are energetically expensive (~36,500 kWh/year in biological and chemical energy consumption required to sustain a Western worker) but infrastructurally diversified. We draw ~80% of our energy from the “Off-Grid” system: Gasoline, Natural Gas, and Food. Only ~4,200 kWh of that burden is transmitted to the electrical grid (residential load).

The Machine Engine (Concentrated & Constrained)

Machines are infrastructurally concentrated. An AI Agent draws 100% of its energy from the electrical grid. It cannot eat a sandwich, nor can it burn gasoline.

When you replace a Human with a Machine, you are attempting to route the entire economy through a 14% bottleneck. We can calculate the “Substitution Penalty” using 2024 production data:

Human Grid Load: ~4,200 kWh/year.

Machine Grid Load: To generate the same GDP output ($150k), a machine requires ~156,000 kWh of electricity (based on the current economy-wide average capital efficiency of ~1.04 kWh/$, a likely understated assumption as Data Centers run at much higher utilization than the average factory).

Recent work by Jones and Tonetti (2026) provides the mathematical proof: in a system of complementary inputs, growth is constrained by the “Weakest Link.”

The prevailing technocratic interpretation is that Human Labor is this weak link—a drag on efficiency that must be automated away.

This is not just a sociological error; it is a fatal strategic error. You cannot ask a human to build a machine whose stated purpose is to replace the human. It’s as inhumane as asking prisoners of war to dig their own graves. It is not a business plan; it is a declaration of war.

To fund the massive capex required to build the Thermodynamic Grid, we need the political and physical buy-in of the population. We are currently selling them “Fear of Replacement.” We need to sell them “Inheritance.” The Meek don’t want to just serve the machine; they want to inherit the Earth it builds.

Until we correct this narrative — until we make the human a beneficiary rather than a target — the grid will remain the binding constraint. The machine waits for the electron because the voter refuses to dig the trench.

The Predatory Nature of Capital Deepening

Standard economic theory and status quo defending economists assume that “Capital Deepening” (investing in machines) raises wages because it makes workers more productive.

This assumes Energy is elastic. It assumes that if we build a Machine, the grid will expand to feed both the Machine and the Human.

In a 14% Bottleneck world, Capital Deepening can be predatory.

The Machine does not just compete with the Human for work; it competes with the Human for current. The AI Data Center pays for the substation upgrade; the residential neighborhood gets the brownout. And the protests begin:

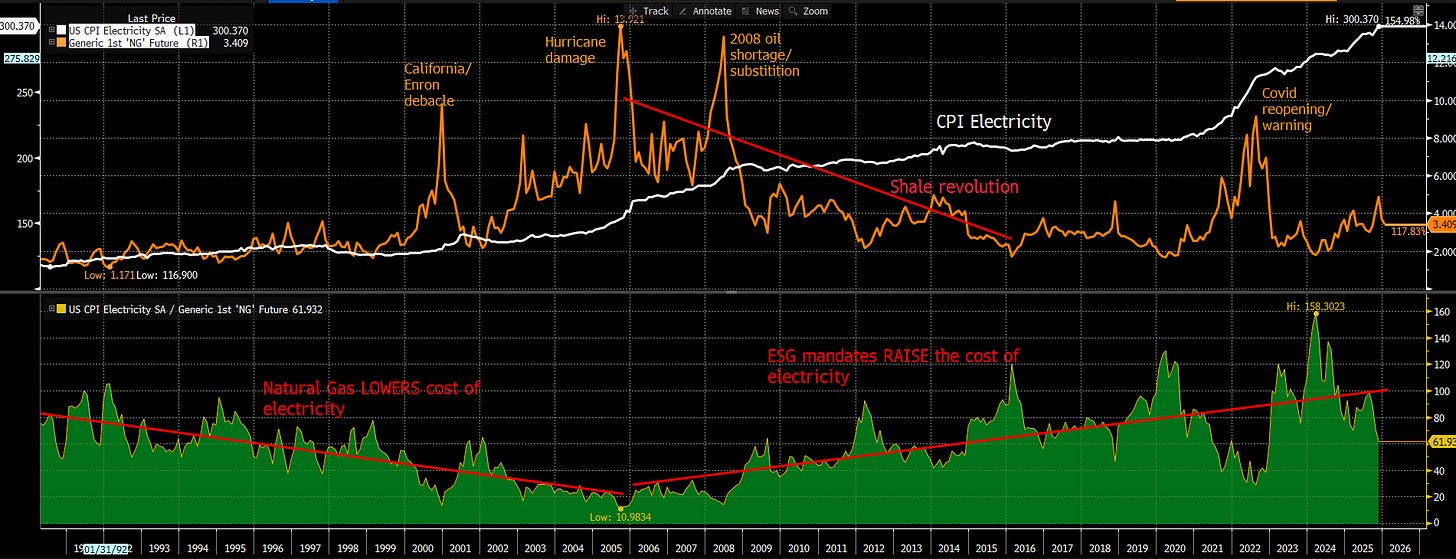

If you doubt the cost of this transition, look at the divergence between the fuel (Gas) and the product (Electricity).

As the chart above illustrates, the cost of Electricity (White Line) has largely decoupled from the cost of Natural Gas (Orange Line).

The Molecule (Orange): Remains cheap due to the shale revolution and “Associated Gas” surplus. More on that later.

The Electron (White): Is soaring in price.

The Ratio (Green): This is the Topology Penalty. It is the cost of grid congestion, ESG mandates, and transmission complexity. We have plenty of cheap gas, but we cannot turn it into cheap power because the transmission layer is broken.

The counterargument is that the grid can be bypassed or modularized via “behind-the-meter” generation, i.e., Microsoft building power plants. This path has been promoted by the Trump administration. This can be done — but only at the cost of turning software firms into utilities and internalizing capital costs that markets price currently as external. Privatization does not remove the constraint; it converts a public bottleneck into a balance-sheet one, raising the marginal cost of capital for every downstream activity.

The issue is not that this capital cannot be built, but that it cannot be built fast enough, cheaply enough, or uniformly enough to avoid a decade-scale binding constraint.

The “Triple Load” Disaster

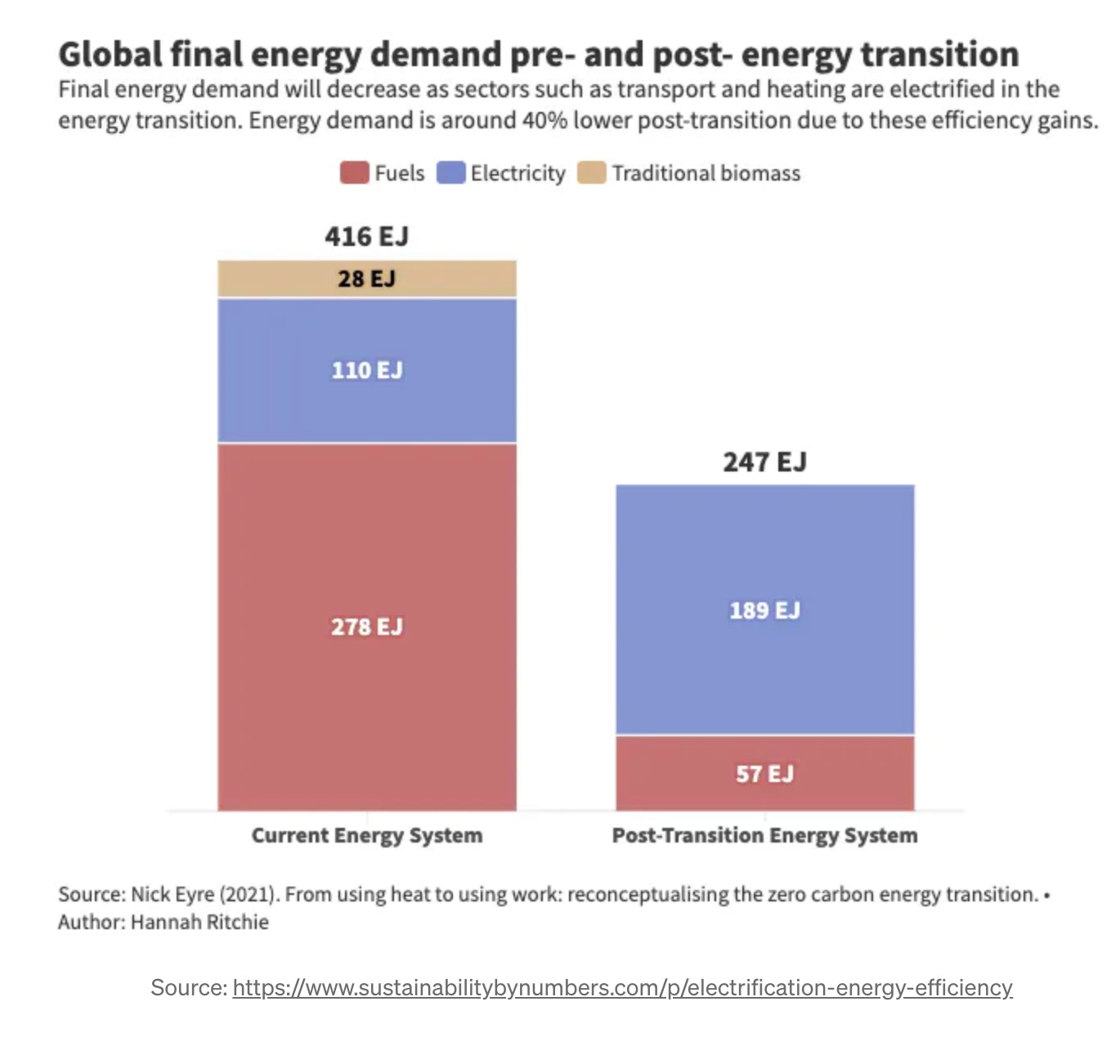

Critics might argue that demographic decline will offset this load. This ignores the Transition Period (2025–2035) discussed in my end-of-year post. We are facing a period of Displacement, not just Replacement.

We are squeezing the grid in a Triple Pincer:

The Legacy Pincer (The Human Stays): The displaced worker is still alive. They still heat their home and drive their car (increasingly electric). Their 36,500 kWh load remains.

The Machine Pincer (The AI Arrives): The AI Data Center comes online to do its job, adding 156,000 kWh of new load to the grid.

The Rerouting Pincer (The Electrification): Even the “efficiencies” we are promised (EVs, Heat Pumps) work against us topologically. When you swap a gas car for an EV, you may save energy in aggregate, but you worsen congestion in the constrained layer that sets the system’s price.

The Net Result: We don’t save energy. We add a massive new layer of industrial demand (Pincer 2) while simultaneously dumping the entire transportation load (Pincer 3) onto the same fragile copper wires used by the legacy base (Pincer 1). The policy goal is to raise the grid’s share—but doing so requires rebuilding the transmission layer itself, which is precisely the binding constraint.

We are trying to force a disproportionate share of future growth through a pipe built for a fraction of today’s load.