Taking a Step Back to Step Forward

Reintroducing a little bit of market, and reframing the overly dense part three with the help of AI

We are “officially” done with my three-part screed on precarity in America. As expected, the think tankers are attempting to weasel out of the debates they so eagerly sought. They won’t get fooled again, so it’s up to us to press forward. I’m going to continue to put the paywall at the end of the piece so that it is available for all to read. This will cease in January with few exceptions. If you’re paying to be here, you deserve to be compensated with proprietary information.

The past few weeks have been among the most brutally exhausting of my career. I woke in my own bed Friday morning for the first time in two weeks after bouncing across seven time zones and 26 degrees of latitude. In a recent interview, I was asked what keeps me awake at night. My answer was honest: “The fear of disappointing people.”

I am going to prepare you in advance—I cannot carry this alone. I have a fiduciary duty to my clients and a moral duty to my family. I cannot maintain this pace as a solo operator. Consider yourself deputized.

Some “professionals” have risen to the challenge. Peter McCormack is bringing English hooliganism to the fight, and I gladly flew across the pond to speak with him. His analysis of the Nick Fuentes phenomenon is spectacular. I may add my thoughts on this phenomenon in future writings. Kevin Erdmann, a housing specialist at the Mercator Institute (where Tyler Cowen holds court), has joined the cause, sharing his very personal interpretation of my work and pushing back against his colleagues. FWIW, I think Kevin’s take on housing is spot on, but note that we have substituted a time-based shortage of housing we need NOW with high real prices that lower fertility and create a longer-term demographic disaster that will ultimately lower real home prices. This has been demonstrated empirically in both China and the United States.

In the last week, many of you took my advice and ran the LLM prompts, sharing the results with friends, colleagues, and politicians. This IS having an impact. I have received inquiries from the highest echelons of the US government. We have a window of opportunity.

The current administration has both genius and madness. The madness is obvious. The genius is being slowly architected under the surface, but it must fight its way through corruption, venality, and cynicism.

To win that fight, we first have to understand the battlefield. We have to understand why the game is rigged. With the help of LLMs, and the benefit of thoughts from Kevin Erdmann, Ole Peters, Peter McCormack, and many others, I have rewritten Part 3, by far the most dense segment, into its own three-part essay. We’ll get some market commentary out of the way and then press ahead.

Giving Credit Where Credit is Due — What the Heck is Keeping Spreads so Tight?

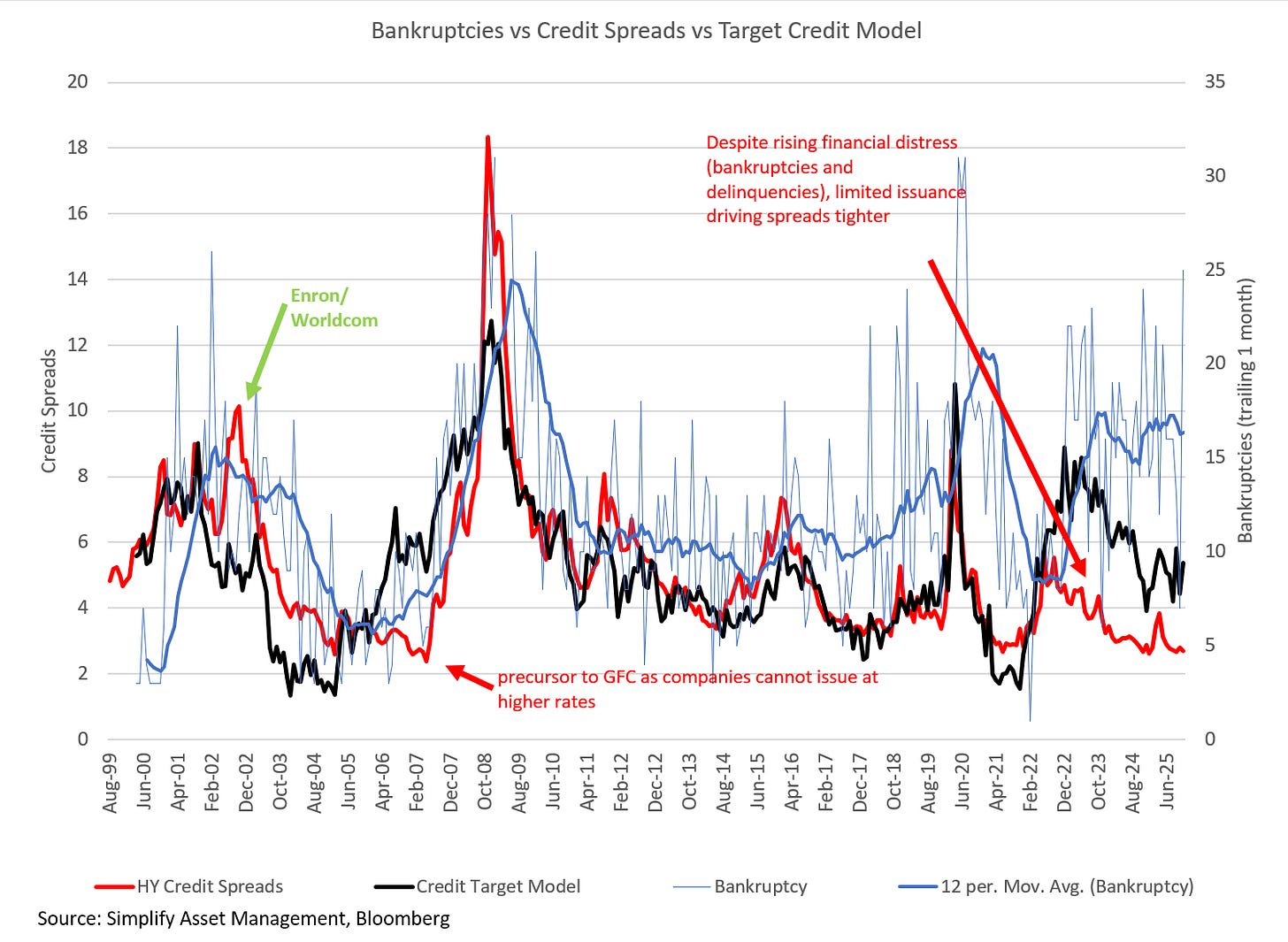

After the briefest of interludes in October and November, credit spreads for cash high yield bonds have again returned to their tightest levels in history. This is occurring despite a surge in realized bankruptcies in the month of November (thin blue line) to the highest non-recessionary levels in history. My models of credit spreads suggest they should be approaching 600bps versus the current levels of 275bps (6%ile versus all history).

Cash spreads are very tight as issuance in high yield has been weak while demand for cash high yield (actual bonds) has been strong. Higher interest rates combined with the growth of private credit and limited interest deductibility for highly levered companies (2017 tax reform limited deductibility of interest expense to 30% of EBIT [operating profit]) has resulted in companies both unwilling and unable to raise their interest expense by refinancing 2020-2021 era low coupon paper. Meanwhile, the higher secondary market yields have resulted in increased cash flow to high yield funds, driving additional demand. Similar to the lead-in to the GFC, spreads are artificially tight while economic conditions are increasingly precarious.

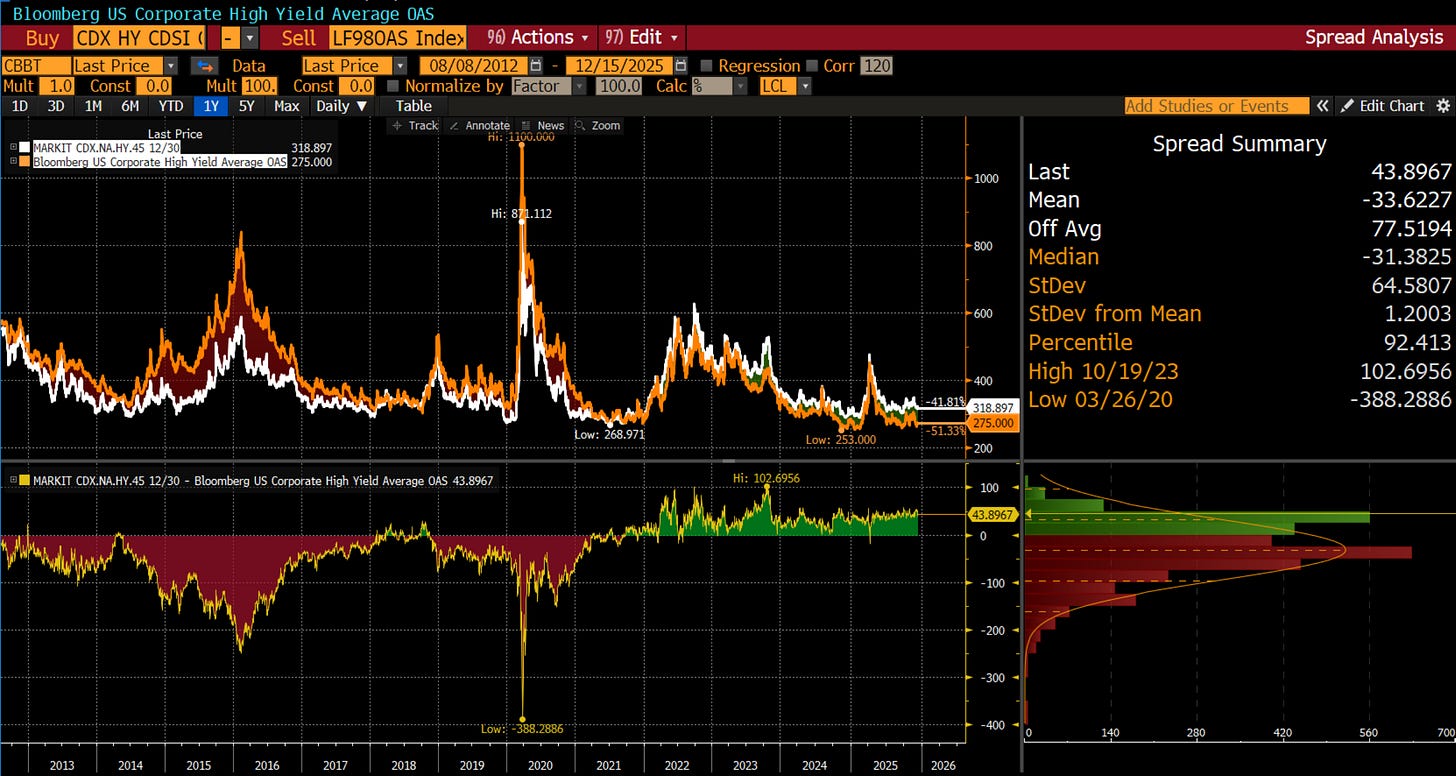

Of course, there’s more to the story. My visit to New York last week included a chat with David Meneret, one of the smartest credit investors I know. David shared with me his analysis of the high yield CDS (credit default swaps) market which has been running with a consistent positive basis to high yield cash. This means “long high yield” synthetically via short high yield CDS delivers significant excess returns:

The basis for high yield CDS is traditionally negative because (1), unlike high yield cash bonds, financing the purchase of CDS as protection is easily levered, and (2) insurance trades at a premium. It has turned positive as the shortage of secondary market paper (also occurred in Q4-2018), combined with strong cash flows to high yield, and competition from private credit has pushed cash bonds tighter.

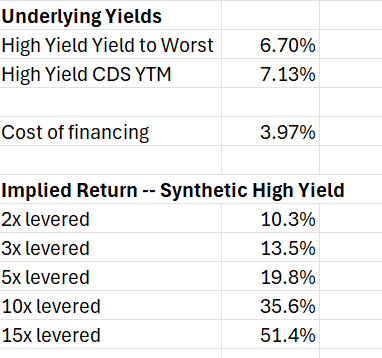

A fund that chooses to leverage exposure to high yield by SELLING high yield CDS can generate extraordinary returns:

Eye-popping indeed. And David points out that this trade is absolutely in play. He identified a single high-yield hedge fund, launched in 2021, with roughly $12B in AUM, that has taken this to the extreme. On his estimates, this fund is levered between 10-15x into a synthetic high yield position, suggesting they represent between 12-20% of the entire high yield market. At that degree of leverage, a 200bps widening of high yield spreads would wipe out the fund. As a reminder, Ralph Cioffi’s Bear Stearns High Grade Credit Opportunities Fund was 10x levered in 2007. Got popcorn?

Back to the coal mines for the rewrite of Part 3 into its own three-part series:

The Rule of 65: Part 1

The Physics of the Trap

“I’m not an economist… my eyes are glazing over. Just tell me what’s wrong.” — Douglas Goldhirsch, Subscriber

The reason you feel like you are running on a treadmill that keeps speeding up isn’t because you are lazy. It isn’t because you buy too much avocado toast. And it isn’t even because of “inflation” in the traditional sense.

It is because we are playing a game that concentrates wealth and income UNLESS we actively choose to redistribute it.

The “Capitalism” Paradox

Let’s say the quiet part out loud: Karl Marx’s analysis that capitalism sows the seeds of its own destruction is “correct.” But his prescriptions were far worse.

Capitalism is unique in harnessing the power of prices to convey information. Shortages are identified by rising prices; excess supply or deficient demand by falling prices. The profit incentive harnesses our desire for leisure and novelty to introduce innovation in a manner that cannot be replicated by central planning.

But because success compounds, capitalism naturally concentrates resources in a manner that is caustic to opportunity for future participants—our children, both born and unborn. To keep the game going, it requires a degree of redistribution from winners to BOTH losers (social insurance) and new players (opportunity).

The Trap: We have flipped that redistribution requirement into a concentration impulse. Instead of recycling wealth to fund new players, we are extracting wealth to protect old winners.

The Equation of Life (The Physics of Concentration)

This isn’t just philosophy; it is physics. In 2011, physicist Ole Peters at the London Mathematical Laboratory proved this mathematically.

He ran a simulation of a “pure” free market using Geometric Brownian Motion—what he calls the “Equation of Life.” The result? In a system where wealth creates more wealth, stability is not the natural state. If you let the clock run long enough without intervention, one person ends up with all the money, and everyone else ends up with zero. (For those who have followed my critiques of Bitcoin, you will recognize this).

It doesn’t matter how “good” or hardworking the other players are. The math of compounding luck ensures that eventually, one player owns the board. We used to call this Feudalism. Today, we just call it “The Economy.”

The Magic Number: Tau (τ)

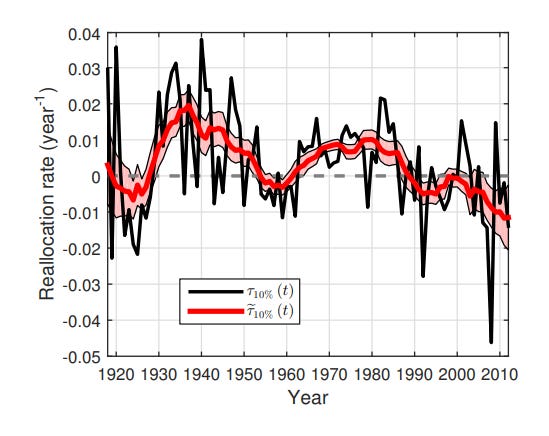

To stop the game from ending in total collapse, healthy societies invent “re-allocation”—mechanisms like taxes, antitrust laws (which force economic winners back into competition), and public investment. Peters calls this force τ (Tau).

When τ is Positive (τ > 0): The system stabilizes. Wealth is naturally pushed back toward the average, creating a broad, robust middle class. This was the physics of the American Dream from 1945–1980.

When τ is Negative (τ < 0): The physics reverse. Instead of the rich stabilizing the system, the system extracts from the poor to pay the rich. The middle class is mathematically repelled from the center, pushed either into the elite or (mostly) into the precariat.

The Diagnosis: For the last 40 years, America has been running a Negative τ experiment. We flipped the switch from “Recirculate” to “Concentrate.”

The “Scarcity Tax” (How Extraction Works)

How does “Negative Tau” work in real life? It usually doesn’t look like a tax bill. It looks like Scarcity.

Housing expert Kevin Erdmann has documented the perfect example in his contribution to the debate. In a healthy economy, if people want homes, we build them. But in our “Negative Tau” economy, we effectively made building illegal through zoning and regulation. This forces prices (and property taxes) higher.

The Shortage: We are currently short about 15 million homes.

The Transfer: Because homes are scarce, the price explodes. Every month, a renter pays a “Scarcity Tax” to a landlord.

This isn’t paying for the value of the structure; it is paying for the privilege of not being homeless. As Erdmann notes, this creates “mass transfers of income from the unhedged (renters) to the hedged (owners)” .

The “Thriving” Trap (The Technocratic Illusion)

This is why a family earning $100,000 feels poor. They aren’t buying luxury; they are paying a “Vampire Tax” just to exist.

Technocrats like Scott Winship at AEI will tell you that you are richer than you think because the quality of goods has improved (a “Hedonic Adjustment”). As we have discussed ad nauseaum, he is technically correct: your TV is better than a 1970s TV. You cannot pay your rent with “better.”

We actually have research that evaluates the inflation rate for the poor versus the rich. Xavier Jaravel of Stanford illustrates the mechanics we have described at length using the brilliant example of organic foods:

Quantity, price and innovation dynamics in the food industry in recent years illustrate particularly well the core ideas developed in this paper. Organic food sales have grown at an average annualized rate of 11.2% between 2004 and 2013, compared with 2.8% for total food sales, in the context of increasing demand from higher-income households. The price premium for organic products shrunk significantly: for instance, organic spinach cost 60% more than nonorganic spinach in 2004, compared with only 7% more today [2015] (Appendix Figure A1). Low inflation for organic products brought down the food CPI, implying that it reduced the rate of increase in food stamps through indexation, although most food-stamp recipients do not purchase organic products. Bell et al. (2015) show how innovations and increased competition led to the fall in organic food prices.

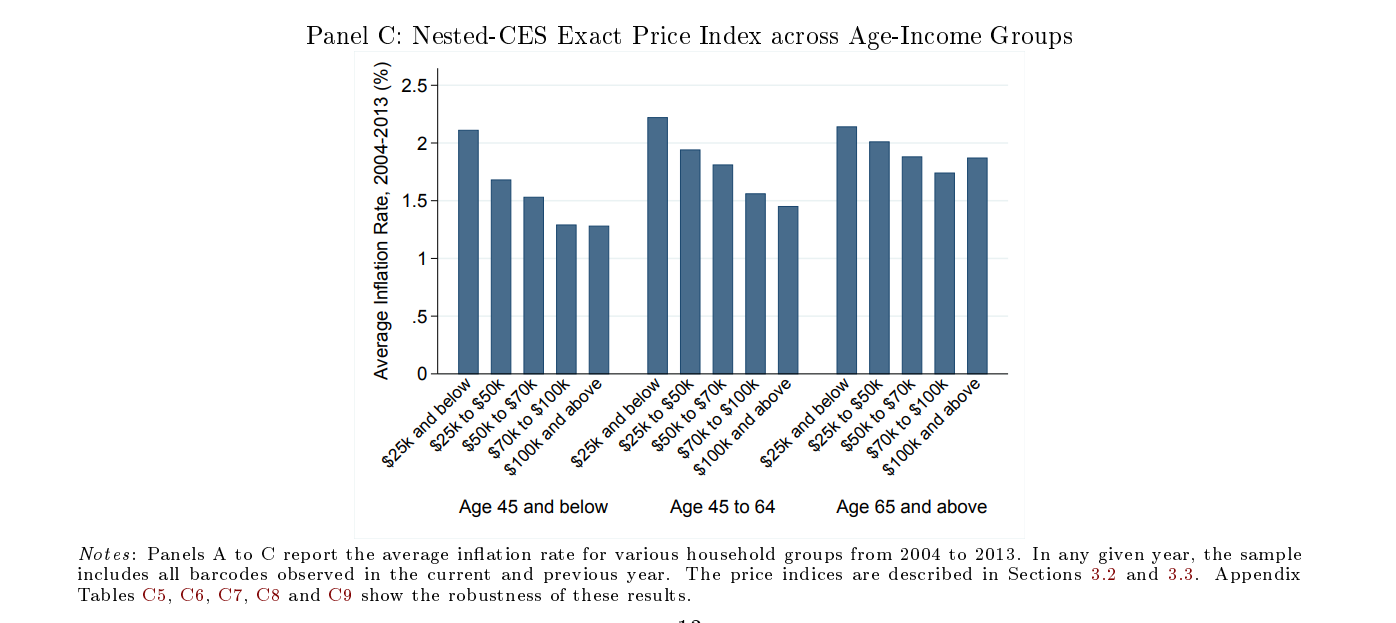

His work, which precedes the inflation surge of Covid, summarizes to a very simple observation — the inflation rate for the poor and the middle class is significantly higher (roughly 0.63% per year) than for higher incomes who dominate the aggregate CPI:

To put this in context, the average CPI for equivalent products over the study period was 1.3%, roughly in line with the levels observed among the highest-income earners. So over 10 years, prices rose (1+1.3%)^10 = 13.7%. For those below $100K in income, prices rose 21%. Cumulatively, since 2003, the equivalent CPI components are up roughly 25%. A similar spread over the period from 2013-2025 would suggest the “cost of being poor” has risen by 43% for these items. Given that post-2020 inflation concentrated in rent, food, insurance, and energy—categories with high expenditure shares among lower-income households—it is almost certain that this divergence widened after 2019. Add 0.63% per year to CPI from 1963, and your poverty line for a family of four shifts to $46,550. Add a similar SCALING to CPI (because the 0.63% was during a period of low inflation), and the poverty line is $97,500 — almost exactly our calculation for Lynchburg, VA. I’m sorry, team, but all roads lead to the same destination. If the CPI understates inflation for the bottom income deciles, then any policy indexed to CPI—including SNAP, poverty thresholds, and eligibility cutoffs—systematically drifts out of alignment with reality.

I am partnering with Truflation to create a “Cost of Being Poor” index and look forward to sharing the results in 2026.

The Conclusion

The economy isn’t broken because of bad luck. It is broken because we switched the setting from “Stabilize” (tau > 0) to “Extract” (tau < 0). We used a not-fit-for-purpose CPI to evaluate benefit levels and demolished the progressivity of the tax code under false trickle-down theories.

We built an economy that mathematically prohibits the middle class from thriving. And, as we’ll discuss next week, we traded Lost Einsteins for Protected Incumbents. Why, as Peter Thiel observed a decade ago, were we promised flying cars but got 140 characters? Because we abandoned productive capitalism for monopoly extraction.

In Part 2, we will look at the Crime Scene—the specific dates and decisions where we flipped the switch and turned the American Dream into an unsolvable math problem.

Upcoming Feature

Starting next week, I will be releasing one interview a week with a political voice I believe deserves amplification. To be absolutely clear, I am receiving no compensation for these discussions. The first interview, Phil Andrew, who is running for the 9th Congressional District in Illinois as a Democrat, has been completed. Phil is literally a hostage negotiator. I can’t think of a better person to send to Congress. And while I can’t claim to have read everything he has written, I find it notable that his campaign website has exactly one mention of Donald Trump — and it’s on a subject I very much agree with: “This work begins by restoring inspector generals to positions that Donald Trump dismantled to shield him and his allies from accountability for fraud and misconduct.” While I don’t agree with Phil on everything (and I won’t agree with anyone on everything), he’s a voice I want amplified.

Next on the table, another Congressional candidate and a candidate for governor of California, where a uniquely discordant Democratic Party transition is opening the path to an outsider.

END