Shaken, not stirred...

Thank you Mr. Fleming

This week I had hoped to expand on my thoughts on passive investing and market structure… and I promise that is coming. But what I expected to be a quietly productive week with my wife visiting two of our college-aged children on the East Coast took an unexpected turn.

I’ve spent the past ten days or so fighting some unknown illness that appeared after a trip to Florida. Conditions deteriorated on Thursday, and by Friday, I found myself in the ER at Marin General with a preliminary diagnosis of pneumonia. Released the same day with a prescription for antibiotics, my intellectual curiosity kicked in, and I’ve spent the last two days ruminating on the feedback loops of human innovation. And writing… slowly… my apologies for the delayed release!

The mid-20th century discovery of antibiotics was the second great health discovery that changed the course of human history in less than 100 years. The first discovery, the germ theory of disease, removed limits on the density of human populations by offering a solution to the inevitable increase in exposure to bacteria and viruses that generate the pandemics and diseases that occur when humans and domesticated animals crowd together with high density. This second discovery removed a significant fraction of the randomness of death by infections that prevented humans from reaching the normal potential lifespan. To put it bluntly, had Alexander Fleming not discovered penicillin, there’s a reasonable chance you’d never read this letter. If you want to read a thrilling tale of human ingenuity in the face of need, I strongly encourage reading the American Chemical Society’s timeline of penicillin. It was far from a smooth path:

Fleming found that his "mold juice" was capable of killing a wide range of harmful bacteria, such as streptococcus, meningococcus, and the diphtheria bacillus. He then set his assistants, Stuart Craddock and Frederick Ridley, the difficult task of isolating pure penicillin from the mold juice. It proved to be very unstable, and they were only able to prepare solutions of crude material to work with. Fleming published his findings in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology in June 1929, with only a passing reference to penicillin's potential therapeutic benefits. At this stage it looked as if its main application would be in isolating penicillin-insensitive bacteria from penicillin-sensitive bacteria in a mixed culture. This at least was of practical benefit to bacteriologists, and kept interest in penicillin going. Others, including Harold Raistrick, Professor of Biochemistry at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, tried to purify penicillin but failed.

“Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence only in an arithmetical ratio”, Thomas Malthus, 1798

It has become de rigueur in our current environment to belittle human advancement in a manner that feels distinctly Malthusian. Our “climate emergency” suggests we must reduce our standard of living by reducing our energy consumption, and many openly celebrate the idea of a reduced human population. Make no mistake, any individual writing that the Earth's carrying capacity is less than current levels is effectively arguing for genocide. There is no alternative interpretation. These arguments are often cloaked in pseudo-scientific “realities,” as Dr. Christopher Tucker has done with his ridiculous polemic, “A Planet of 3 Billion: Mapping Humanity's Long History of Ecological Destruction and Finding Our Way to a Resilient Future A Global Citizen's Guide to Saving the Planet.” To save you the effort of reading it, I’ve attached an Earth Day 2020 video of the smiling Dr. Tucker discussing his book:

You can jump to the most relevant points at minute 29:48 where he discusses the “scientific” approaches to the question, “How many people can the Earth support?” He highlights that there are five separate approaches to this question, ranging from energy limits to his favorite, “geographically-explicit biocapacity thesis” (unsurprising for a geographer), which plays into his “P3B” thesis.

As you might guess, Dr. Tucker suggests that those disagreeing are simply innumerate:

“I just want to see their data, and I want to see their math.” — Dr. Christopher Tucker, Chairman, American Geographical Society

In other words, “follow the science!”

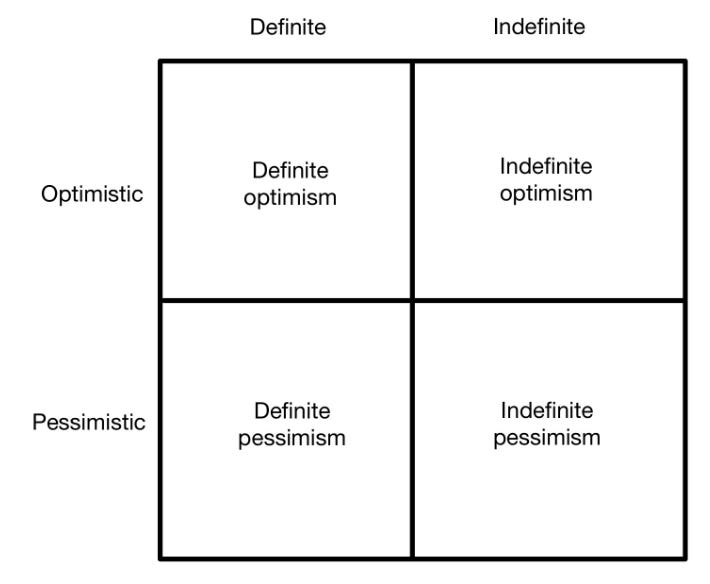

These too often repeated words have taken on a religious dimension in our post-Covid era, but they alternately mean “Don’t question the experts” or, in a perversion of the scientific method, “be skeptical of claims that require future innovation.” The first largely takes care of itself. The second plays well into a matrix of Peter Thiel’s from his book, Zero to One, where Dr. Tucker has embraced “definite pessimism.”

“A definite pessimist believes the future can be known, but since it will be bleak, he must prepare for it.” — Peter Thiel, Zero to One

Peter, writing post-GFC, goes further, noting that this matrix does a good job of describing the political realities of our world and notes that the US has cycled from “Determined Optimism” in the 1950s & 60s to “Indeterminate Optimism” and is now, like Dr. Tucker, possibly shifting towards China in determined pessimism:

Peter is an exceptionally thoughtful individual, and time has certainly favored his interpretation of the direction that the US was heading. Certainly, in 2014 we might have debated whether the future appeared uncertainly optimistic for the United States, but even prior to Covid, that debate seems settled — “Majorities predict a weaker economy, a growing income divide, a degraded environment and a broken political system” (Pew Research Center, 2019). I don’t agree we’ve moved into “determinate pessimism” because we still have no idea how to solve our “unsolvable” problems. During Covid, I would suggest we’ve clearly veered into “indeterminate pessimism”, effectively a nihilism that says, “Nothing really matters; we’re all f’d”:

“And then there is the pessimistic indeterminate quadrant. This is probably the worst of all worlds; the future isn’t that great and you have no idea what to do.” — Peter Thiel, notes from Stanford CS183 by Blake Masters

The pessimism is increasingly real. Note the record divergence between consumer confidence (inverted in white) and unemployment rates. This divergence cannot be explained by gasoline prices, inflation, etc. It appears to coincide with the invasion of Ukraine, which suggests that global events are playing a larger role in our outlook than historically, but even before then, we saw notable divergences around the Trump election.

In my view, this is simultaneously increasingly self-fulfilling and untrue, born of the perceived helplessness in the face of scarcity and lack of self-agency that emerged in the post-Covid era. How can we feel hopeful when our political leaders suggest the solution to shelter in place is to stock our freezers with ice cream we can get in the mail?

“I don’t know what I’d have done if ice cream had not been invented” — Nancy Pelosi, April 2020

I spend my time talking about penicillin and energy efficiency while our elected officials celebrate ice cream. Is it any wonder I will never be a world leader? But the reality is that we have faced scarcity before and triumphed. Witness the 1981 diatribe, “The Politics of Scarcity.”

“Although the Reagan administration has advocated drastic changes in national energy policy, the nature of the problem remains basically the same. The scarcity of petroleum is unique both because of its importance to the American economy and because of the impact of OPEC” - The Politics of Scarcity, Robert C. Weaver, 1981

We know how that worked out — in real terms, oil prices have fallen roughly 50% from 1981. In nominal terms, they have risen 50% in 41 years (less than 1% per year). Relative to median family income, they have fallen 53% even after recent jumps (and declines since I questioned the demand narrative):

And this ignores the fact that we get more useful products per barrel of oil than in 1981 (refinery efficiency and increased recycling) and more output (e.g. miles per gallon) per unit of refined product. As a percentage of GDP, oil is now less than 3% globally, down from nearly 10% in 1980. Realistically, scarcity of energy supplies is simply not credible when compared to any period of history except the most immediate past, as oil intensity has continued an almost uninterrupted decline since the peak in 1973:

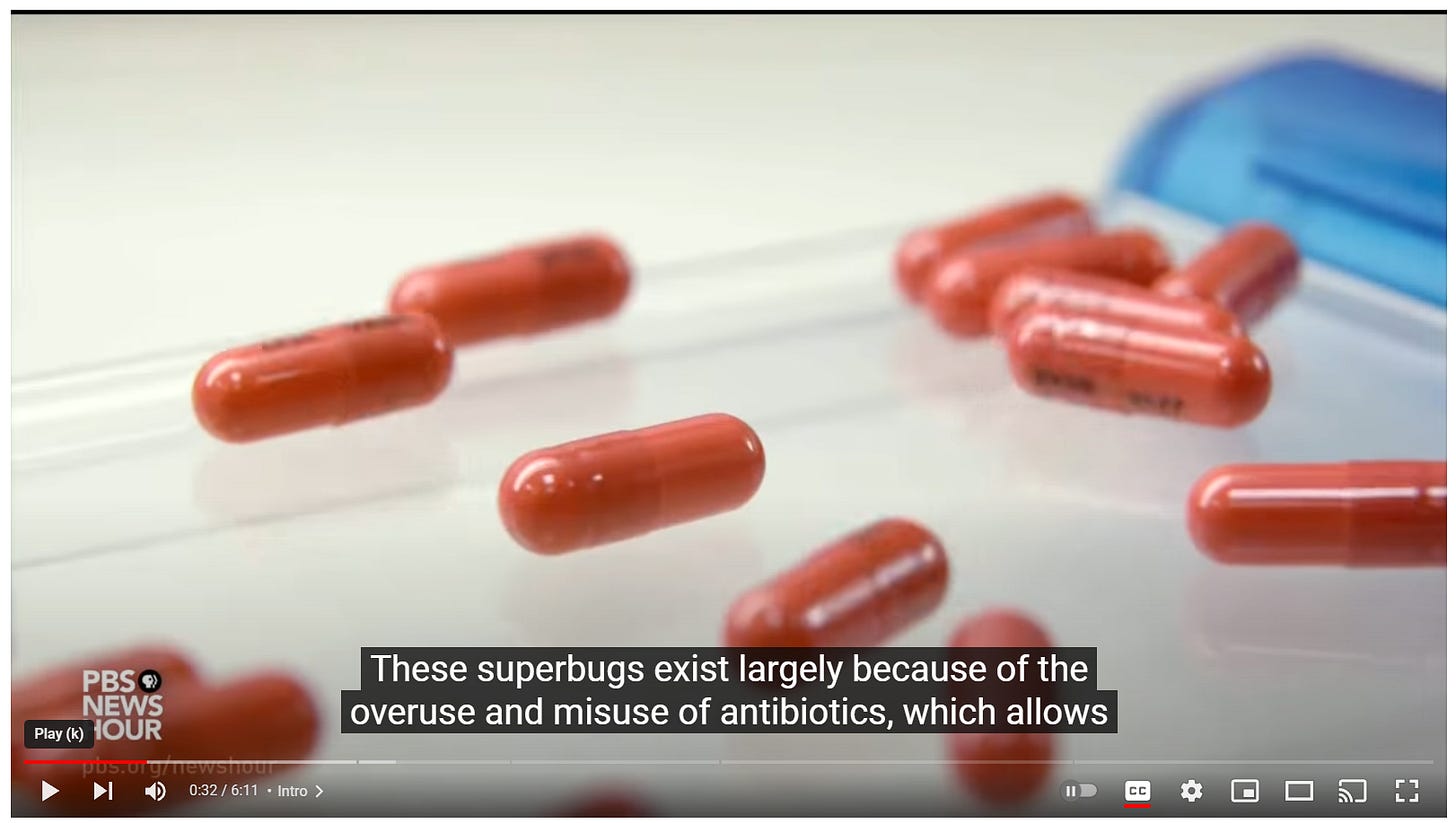

Likewise, scarcity of the new innovation of penicillin required rationing in 1943, and yet today, our concerns largely focus on overuse:

1943: A newspaper account in the New York Herald Tribune for October 17, 1943, stated: "Many laymen - husbands, wives, parents, brothers, sisters, friends - beg Dr. Keefer for penicillin. In every case the petitioner is told to arrange that a full dossier on the patient's condition be sent by the doctor in charge. When this is received, the decision is made on a medical, not an emotional basis."

2019:

Imagine the difference in lived experience between 1943, when hope appeared but needed to be rationed, and two years later:

Production of the drug in the United States jumped from 21 billion units in 1943, to 1,663 billion units in 1944, to more than 6.8 trillion units in 1945, and manufacturing techniques had changed in scale and sophistication from one-liter flasks with less than 1% yield to 10,000-gallon tanks at 80-90% yield. The American government was eventually able to remove all restrictions on its availability, and as of March 15, 1945, penicillin was distributed through the usual channels and was available to the consumer in his or her corner pharmacy.

The astonishing declines in mortality from the introduction of modern antibiotics (first sulfonamides [notation S]) and then penicillin (notation P) on septicemia (bacterial blood poisoning) mortality rates are almost unfathomable:

And these declines were in addition to the roughly 80% declines experienced in the 19th century due to the introduction of (relatively) modern sanitation techniques. In 1800, a woman had a roughly 47% chance of dying during childbirth due to a ~8% probability per childbirth and ~7.5 deliveries per woman. By 1900, that had fallen to 8.2%. By 1960, it had fallen to less than 1%. Today it is roughly 0.02% in the United States.

To put it in extremely straightforward terms, the economics of women change radically when the incidence of fatality from a nearly universal experience (childbirth) falls from ~50% to 0.02%. Society grows on surplus, and the net present value of women as educated, productive members of society explodes when we largely eliminate the risks that they, or their children, will die without the opportunity to return economic value to society over and above our initial investment of resources. Which is the great irony of Dr. Tucker’s views:

“growth for growth’s sake — I think that’s the big problem that we have to grapple with” — Dr. Christopher Tucker

“There are strategies for bending the population curve” — Dr. Chris Tucker

The ability of our society to bend the population curve in the manner he suggests is contingent on “growth for growth’s sake.” Nobody planned the discovery of penicillin or sulfonamides, but it is not a coincidence that both discoveries emerged as men and women were lifted from the daily drudgery of scraping out a subsistence existence to an existence in which basic necessities were largely met before you rolled out of bed.

There is one point of agreement between Dr. Tucker and myself:

“The longer we wait, the harder it gets and the more energy that will have to be expended to do it.”

We know the solution — more energy. Increased energy creates the capacity for more work and more surplus. It addresses shortages and pollution. The application of energy is the solution to the problems that Dr. Tucker pessimistically identifies, as he himself admits:

“We’ll need 40 terawatts to remove plastics from the oceans.” — Dr. Christopher Tucker

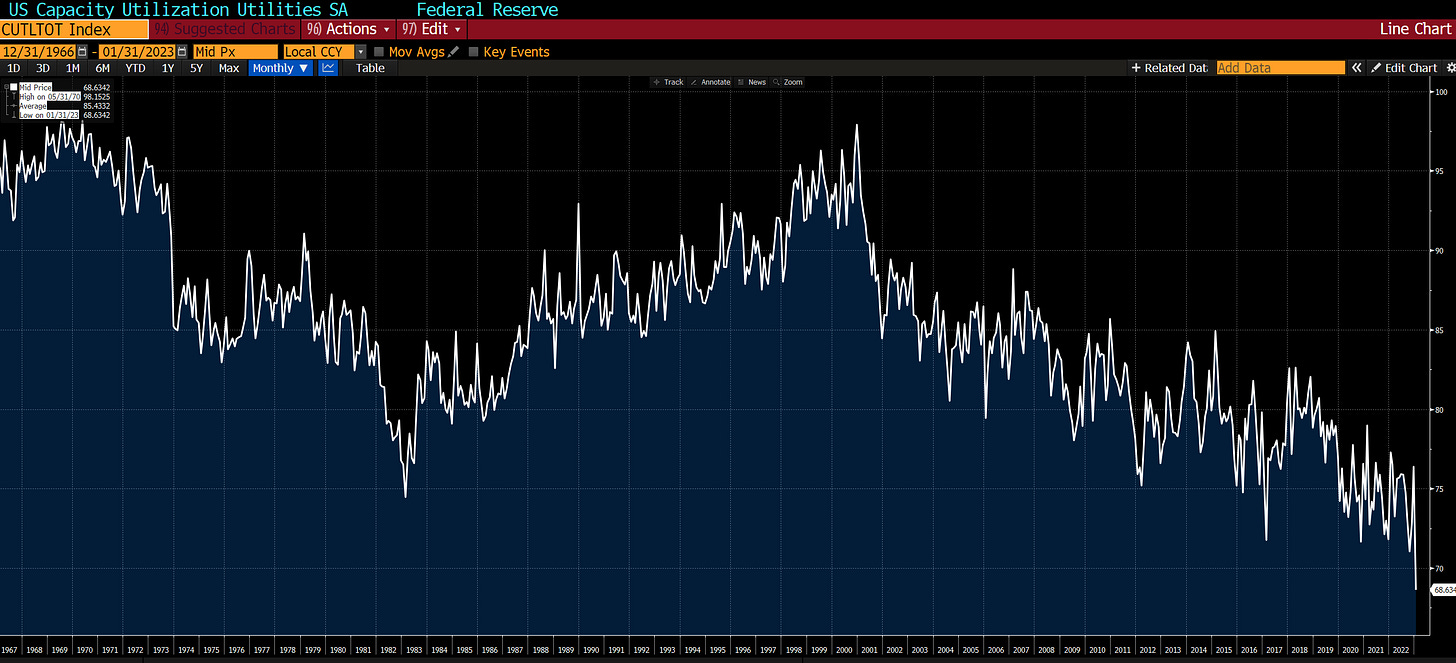

This does not necessarily mean more oil & gas, although we may experience aggregate demand increases for fossil fuels during the transition period. Nor, for that matter, more intermittent “renewable” sources. Notice the collapsing utilization of US utilities as we’ve transitioned from largely baseload power to intermittent sources (including natural gas “peakers”), which necessitate large quantities of spare capacity to offset episodic unexpected demand due to intermittent solar, wind, or hydro (in drought-stricken areas).

As I put it in a tweet earlier this week (as I lay in bed):

With the US growing increasingly pessimistic about future opportunities, we have to recognize that these expectations can become self-fulfilling, as the Richmond Fed identified in January 2021 (right before the divergence, btw):

Expectations about the future are important drivers of the economy. For instance, a more pessimistic outlook can lead households to save more and firms to hire less. These individual decisions can lead to aggregate fluctuations in output, employment, and prices. Survey data allow us to measure how the expectations of different economic agents fluctuate over time, providing evidence to test theories of expectation formation and allowing us to quantify their effects. — Richmond Fed, Jan 2021

But I am not yet, ready to declare defeat. In fact, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, I am increasingly energized by the incredible innovations directly ahead of us. To reintroduce Peter’s matrix:

We’ve been here before, but I can’t help but wonder if the data are concealing our reality. Yes, unemployment is low, but people are miserable in their employment!

And while asset markets (including equity, credit, and housing) are closer to peak valuations than trough valuations, many of you know I have an alternate explanation for why the equity risk premium is near a record low despite rising rates. This provides us with a convenient jumping-off point to return to the passive story next week.

Once again, thank you for reading, and I look forward to your comments.

Sorry you had to write it while sick, but this was one of your best yet

Consider me a definitive optimist, reading voices like you, Doomberg and others confirms my faith and trust in human intelligence to find the way forward.