Hot Shots Part Deux

A subchapter on "What Bogle Got Right"

OK, we’re starting to cook with gas now… the book's flow is really taking shape and my readers have been providing excellent feedback. With that, the Top Comment:

Top Comment

Jim Brown comes out of the backfield with a crushing attack: It seems a broad theme is emerging. The "science" of finance (diversification, efficient markets, deferring to experts) seems to have been adopted and encoded into laws and regulations governing large pools of investment dollars. But in so doing, the laws and regulations changed the nature of markets, rendering the original "science" obsolete. If I have stated that correctly, I suggest you offer as many concrete examples as possible to illustrate this point.

I am looking forward to the next installment.

MWG Response: Jim, you are 100% on point and inspired me to write a “subchapter” on what Bogle got right and how, using the most dangerous words in finance, “it’s different this time.” The concrete examples are a criticism my editor offered, noting that the “stories” and “people” make a book sing. I will be rewriting chapters 1, 2a (included today as first draft), and 6 to incorporate more examples. Please bear with me on this. But I figured a section on “What Bogle Got Right” was an appropriate segue to this point, steelmanning the arguments FOR passive while noting that the real problem is not “passive” per see (it’s just one of many possible strategies), but instead the regulatory advantage conferred on passive in the 1990s and 2000s. Hope you enjoy!

The Main Event

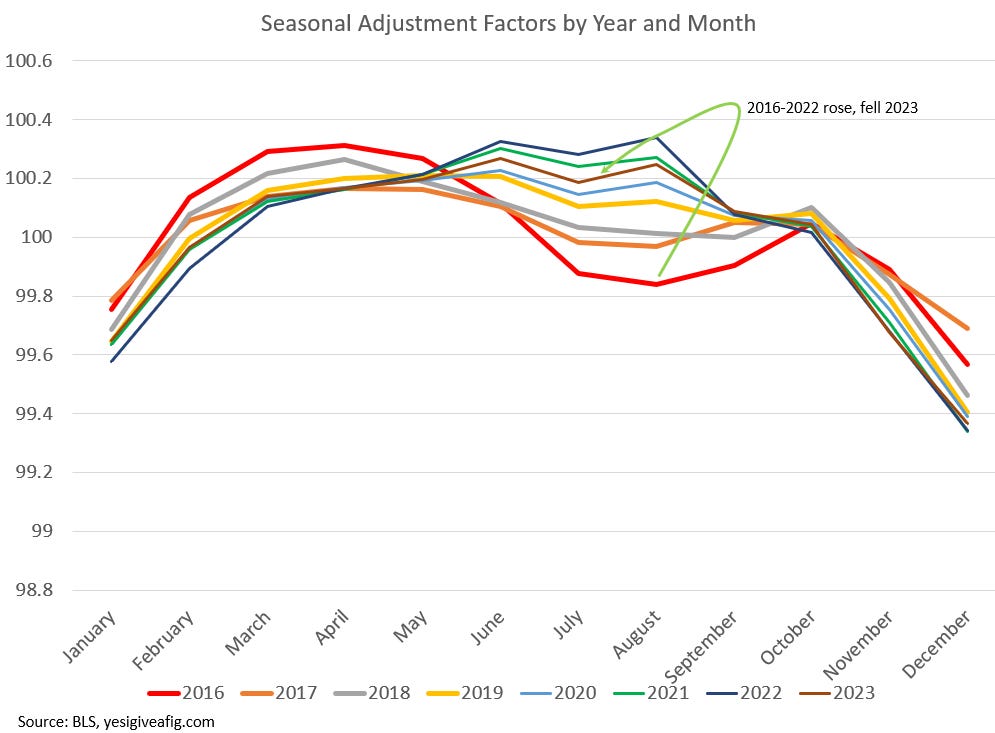

As I have indicated, the next few weeks are dominated by the book. But this week’s “hot” inflation report requires acknowledgment that my hypothesis from last September that residual seasonality in inflation would lead to Powell’s hesitation to cut rates has proven correct.

My analysis suggests Powell has created a trap for himself—cutting interest rates modestly from these levels will not help the indebted and will harm the wealthy. A seasonal resurgence of inflation (which has HELPED the transitory case over the summer, but will reverse into Q4) will lead him to be less aggressive in cutting rates, further increasing the risks of the “phase change” of credit defaults.

This has, unfortunately, come to pass and you will note that the popular press has finally begun to recognize the default cycle that is emerging:

The great irony is that the lax underwriting standards of the last decade that led to a surge in “cov-light” debt documents have forced debtholders into accepting “out-of-court” restructuring that is concealing the magnitude of this cycle. Perhaps extend and pretend will again carry the day, but a strategy that worked well in a falling rate and recovering growth environment is a dubious one with today’s higher rates and weakening economies. I remain unconvinced.

Meanwhile, I encourage you to take a look at Truflation’s SUB-indices. Yes, egg prices are up sharply on bird flu driven shortages, but MARKET-BASED prices across the rest of the universe are not accelerating — they are falling:

And with that, let’s look at what Bogle got right. For Jim Brown, I’d note that the final version of this section will likely include a discussion of the transition from Max Heine to Michael Price at Mutual Series Funds in 1988 and the subsequent sale to Franklin Templeton in 1996. Gotta include the stories!

Subchapter 2: The Demutualization of Asset Management—How the Industry Lost Its Way

John Bogle, the late founder of The Vanguard Group, was a tireless advocate for investors, often warning that large segments of the asset management industry had drifted from their original mission. He believed the shift from mutually owned organizations to for-profit, shareholder-owned entities—demutualization—changed asset managers' incentives and harmed investor interests. Yet, to fully understand this transformation, we must look back to the Great Depression, when a very different crisis spurred another round of structural reforms, culminating in the Investment Company Act of 1940 and the rise of the mutualized model.

The Legacy of the Great Depression and the 1940 Act

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression devastated public confidence in financial institutions. Widespread abuses— from insider trading to opaque fund management — contributed to the crisis, prompting lawmakers to enact sweeping reforms. Among them was the Investment Company Act of 1940, which mandated stricter regulation of investment companies, including mutual funds.

Why Mutualize the Industry?

In the wake of the 1930s debacles, policymakers wanted to ensure that fund managers were held accountable to investors, rather than operating as self-serving entities. Under the Act, mutual funds faced rigorous disclosure requirements, governance standards, and fiduciary duties, reinforcing the idea that investor interests should come first. This environment led to the growth of mutually owned fund companies, where fund shareholders were effectively the owners of the management firm. The goal was to prevent a repeat of the 1920s excesses by aligning managers' profitability with investor success.

By the 1940s and 1950s, these mutualized structures gained traction as investors gradually returned to the stock market. Fees were relatively low, transparency improved, and the model emphasized a fiduciary culture—precisely what the architects of the 1940 Act had intended.

Cycle of Abuses and Reforms

In the early 20th century, unscrupulous practices led to the Great Depression-era reforms, which yielded mutualized asset management. For all its benefits, this mutualized era had its own downsides — allegations of expense-padding and unprofessional management within some mutual organizations. Critics said the mutual model lacked the disciplinary force of external shareholders and had insufficient capital-raising capabilities to modernize swiftly.

That criticism paved the way for demutualization—a conversion to corporate ownership models that, in theory, would curb inefficiencies and "professionalize" asset management. But as we'll see, these reforms set the stage for another wave of abuses.