You're Gonna Need Another Drink

With Inflation Debate Back in the Headlines, Let's Revisit the Beveridge Curve

Summary:

Inflation rates are falling rapidly, but the Fed continues to emphasize their fight against inflation. This is an error.

The primary trend of real interest rates remains lower. Slowing population growth will reduce the demand for borrowing and therefore the trend level of interest rates in the long run.

The narrative of secular inflation driven by forces such as aging demographics and de-globalization is a fundamental misreading of source documents and a projection of lazy analysis. These explanations are oversimplifications based on recent events.

The strong labor market data continues to mislead, with job openings data obviously suspect. More likely, we are experiencing a labor mismatch, particularly between skilled and unskilled workers and this suggests a very different interpretation of current conditions.

Top Comment:

Brian Nurick: Excellent information (referring to last week’s Bitcoin post). Thank you for writing this, very helpful and great mining cost information to share with my fascinated kids, they can understand this.

MWG: Brian, glad you found it helpful. The data has always been out there. The question is “Why weren’t you being shown it?”

The Main Event:

The headline for the week was better than expected inflation with both core and headline CPI modestly beating expectations. There have been a few excellent posts on the topic. The first, from Barry Knapp at Ironsides Macro, was the genesis of much of today’s post. Barry and I had an extended conversation in Twitter DMs and I’m thankful for his thoughts as a seriously smart guy and former Barclay’s strategist. I have relied on his insights for years. He’s also generously offered a 50% off discount to YIGAF subscribers. I encourage checking out his work.

The second piece was from Mike Konzcal, whose work I’m less familiar with. But he had an excellent post that I encourage reading.

Of course, the immediate reaction to the CPI beat was a rally in bonds, for which I’m grateful; unfortunately, the Fed is likely to be unphased with Fed Governor’s Waller, Goolsbee and even Kashkari announcing they would persist in their inflation fight. Kashkari managed to suggest that a new stress test should be introduced to test banks for risks of exposure to inflation:

"Central banks' fight to bring inflation back to target and preserve anchored expectations must succeed," Kashkari said in an essay, adding that policy rates may need to rise further. "One way supervisors could ensure banks are prepared is to run new high-inflation stress tests to identify at-risk banks and size individual capital shortfalls." — Neel Kashkari

This reminded me of the “Fed Uncertainty Principle” introduced back in 2008 by Mike “Mish” Shedlock:

The Fed, in conjunction with all the players watching the Fed, distorts the economic picture. I liken this to Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle where observation of a subatomic particle changes the ability to measure it accurately…

The Fed, by its very existence, alters the economic horizon. Compounding the problem are all the eyes on the Fed attempting to game the system.

The Fed cannot change the primary trend in interest rates. However, the Fed can exaggerate the trend, temporarily slow it, or hold the trend for an unreasonably long period of time after the market (without Fed distractions) would have acted. This leads to various distortions, primarily in the direction of the existing trend.

Now I happen to disagree with Mike (and many, many others) on the primary trend of interest rates. In my view, the logic is simple and inescapable, offset by nonsense which we’ll discuss in a moment. Rather than take my word for it, this excellent post by Jesse Edgerton, formerly of J.P. Morgan and now head of quant economics at TwoSigma, does a great job of laying out the logic as most were willing to accept it in 2021:

Economic theory suggests that the supply of savings and the demand for borrowing combine to determine real interest rates. Many economic models posit that much of the flow of funds from savers to borrowers is effectively a flow from older generations to younger generations. Savings from wealthier older generations fund consumption, education, and home buying by younger generations, as well as the accumulation of business capital for younger generations to work with. If population growth slows permanently, future younger generations will be smaller relative to older generations, and the demand for borrowing will fall relative to the supply of saving, reducing the trend level of interest rates in the long run.

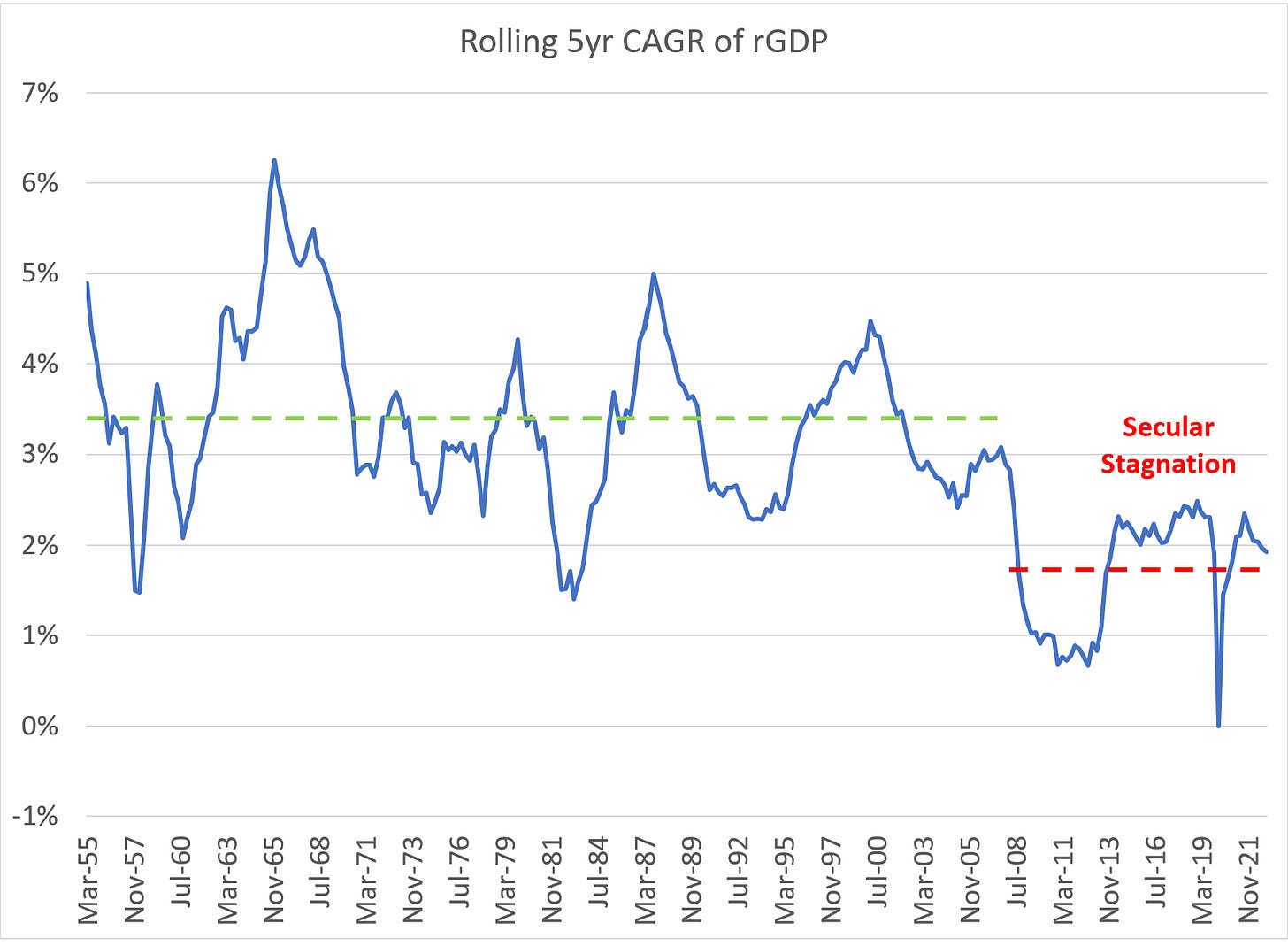

We really didn’t have to worry much about the contra-argument at the time. We had Japan. Of course, there were many convinced that the Fed was artificially manipulating interest rates lower, but the evidence was fairly clear that both real and nominal GDP had slowed markedly despite low interest rates. This was the era of Secular Stagnation: