Why We Blame the Boomers

It wasn't the individual choices, it was the collective choices

This was a very active week and there are literally a dozen topics worth discussing — from fElon hijacking the TSLA earnings call to argue his pay package is “necessary” to offset the evils of passive governance, to the growing awareness of fraud in auto lending (hello old friend CVNA), to the sharp corrections and subsequent recoveries in everything from high beta to gold. But it’s my Substack and I’ll whine if I want to.

A few months ago, I appeared on Adam Taggart’s Thoughtful Money podcast and made an intentionally inflammatory statement:

“We have had enough of the Boomers at this point.”

It got “comments” (including angry emails to my firm, Simplify):

Yeah, Michael Green showed his resentment of boomers upfront, so I am guessing he is a Xer. Xers tend to resent boomers and their millennial offspring. The irony of his boomer comments is that generations before boomers paid very little into all of the social safety net programs and received 3-5X or more in benefits. For example, when I go on the social security website, it tells me I have paid in almost $750,000 in combined payroll taxes for retirement and Medicare. I doubt I will recoup that number in retirement much less the lost interest earned on those funds. I read the other day that over 60 million Americans now earn money on social media of some type. Are they paying taxes? I doubt many of them are. The travesty of the BBB Trump signed is that Congress chickened out on reinstating social security as completely tax-free, the way it was the first 40+ years.

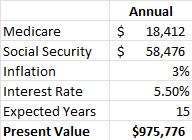

Good guess, Joe, I am indeed an Xer. Bad guess on both the economics of your contributions and my motivations. Let’s hit the first part. Social Security and Medicare are social insurance policies designed to eliminate penury in old age. The current EXPECTED economic value for MauiJoe, given his payments, is something like:

Should Joe, apparently living in Hawaii, live to the 20%ile of our population that value climbs to approximately $1.3MM. Is it a great return on investment? No. Is it an insurance policy that provides significant peace of mind? Absolutely.

But that has nothing to do with my complaints about the Boomers.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the United States experienced a demographic and economic alignment that should have produced the strongest public balance sheet in modern history. A vast generation entered the labor force, female participation expanded, productivity continued, and real wages rose. By any conventional logic, the fiscal position of the government should have strengthened. Instead, the national debt grew, savings rates fell, and public investment collapsed.

The explanation is not merely that taxes were cut or spending rose. It is that the nation mistook a demographic dividend for a permanent economic transformation and built its institutions accordingly. What followed was a half-century experiment in privatizing public prosperity—an experiment that enriched one generation while leaving those that followed with inflated assets, diminished opportunity, and a hollowed-out fiscal state.

The Squandered Dividend

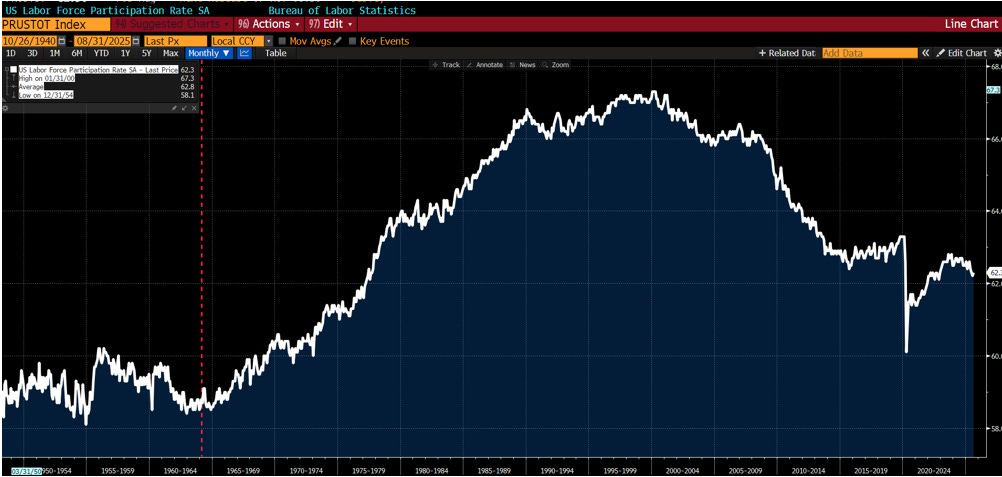

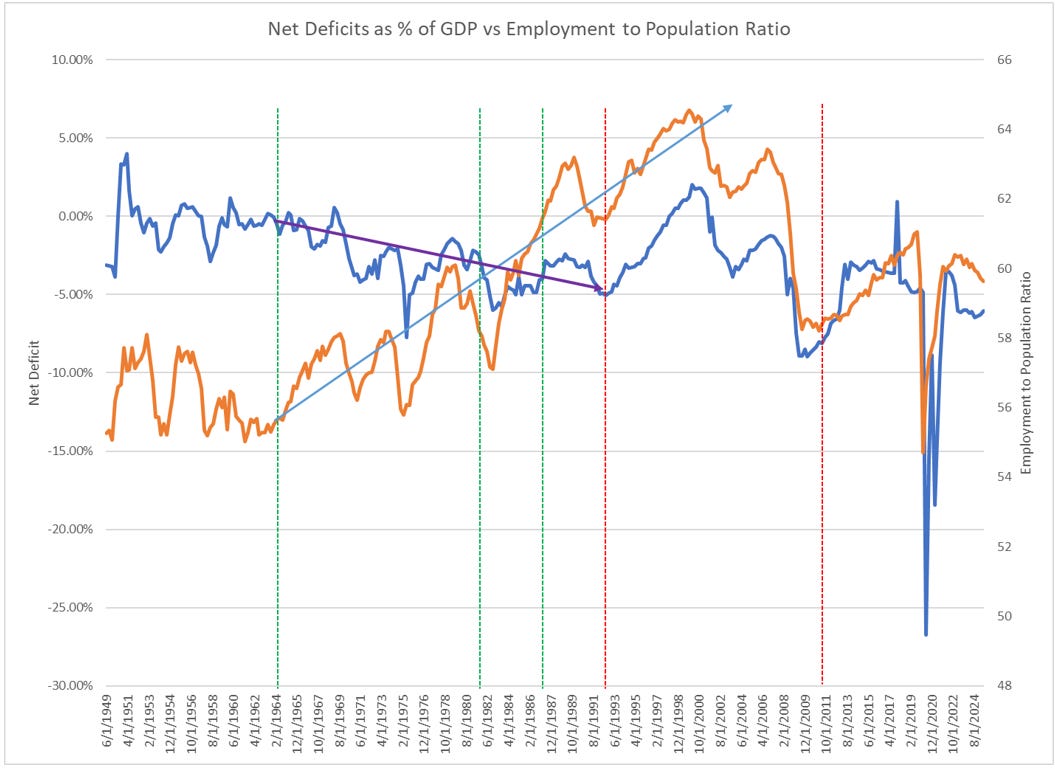

The economy immediately after WW2 saw labor force participation largely unchanged as Rosie the Riveter handed in her wrench for an apron and jobs were transferred to returning soldiers. But by the early 1960s, with the Baby Boomers beginning to enter the workforce, the United States stood at the threshold of what should have been a golden age of fiscal consolidation. More workers meant more taxpayers, fewer dependents, and less need for cyclical deficits. We can demonstrate this with a simple model of Federal deficits as % of GDP vs employment to population ratio. Major tax reforms are noted with dashed lines, green for cuts, red for hikes:

The 1964 Kennedy–Johnson tax cuts (passed in Feb 1964, but retroactive to Jan 1964) were the first tax cuts that changed that trajectory (purple line). They were enacted at a moment when unemployment was locally high at 5.7%, but private demand was strong; policymakers were still operating under Keynesian assumptions of chronic underemployment. The effect was to redirect a portion of what would have been government saving into private consumption. The policy “worked” in the narrow sense that growth remained strong, but it established a precedent: expansionary fiscal policy even in the absence of slack. It also happened just as the first Boomers turned 18 and entered the labor force en masse, stalling what should have been a major fiscal consolidation.

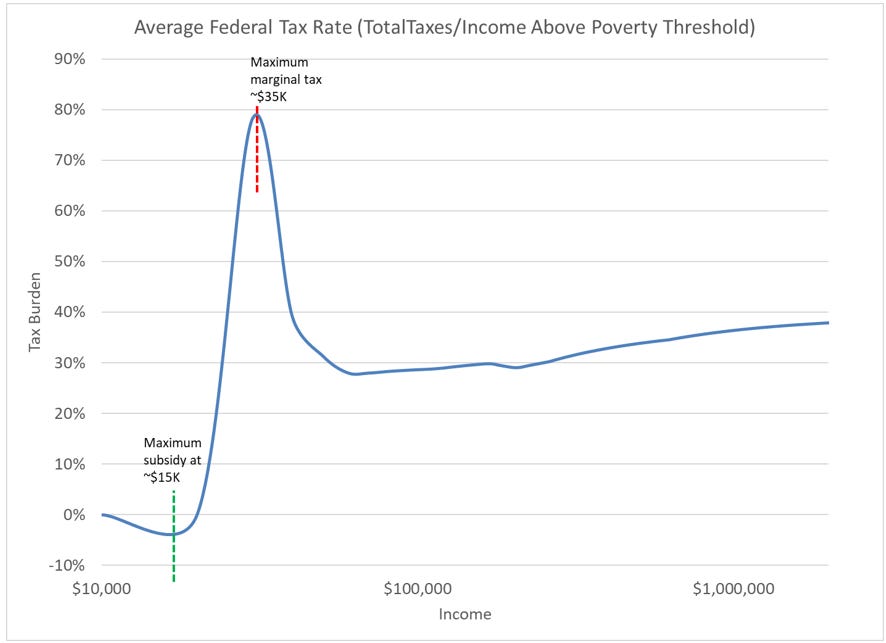

The Reagan tax reforms of the early 1980s lowered marginal rates further while shifting the burden toward payrolls. The result was a paradox—lower taxes at the top, higher taxes at the middle (largely through FICA and use taxes), while larger structural deficits were created by an explosion of entitlement spending (Great Society) and regulatory creep.

Today, the tax rate is “progressive” in only the loosest sense. “Yes” the rich pay more, but the marginal tax burden is most egregiously borne by those barely escaping poverty: