Why Bother Being Better?

Wrapping Up -- with encouraging signs that passive is getting more and more attention

What I’m Reading/Listening to Now:

I did have the opportunity to listen to two Meb Faber podcasts this past week, both touching on passive.

The first was Michael Maubisson. At roughly minute 49, Michael indicates that he’s starting to do some real work on the impact of passive investing. Unfortunately, he also betrays that he’s ignoring the most important insights by suggesting that “obviously you’re buying everything in proportion to its market cap and therefore you’re not changing anything.” This is wrong. Unless stocks are PERFECT substitutes for each other, they will each have unique supply and demand curves with their own elasticity (change in price for change in supply+demand). Therefore ANY purchasing activity WILL change relative prices and WILL change future capital allocation. The only defense of “passive” investing was when we believed it was passive (ie it never transacts per Bill Sharpe). Once you accept that they transact, as Michael apparently has, then the answer is very straightforward that market cap weighting is only one of several allocation schemas and that due to the unique mechanics of order book design/market making (Bouchaud), the largest stocks are going to be advantaged in that model.

The second podcast was Rob Arnott who was reviewing his new NIXT index. This was very interesting for two reasons. First, Rob has constructed an index that embeds the “migration” theory across factors from Fama French’s 2006 paper, Migrations. He discovers that if he constructs an index that simply buys stocks that fall out of the S&P500 and sells stocks that migrate INTO the S&P500 he creates an outperforming benchmark that looks nearly identical to the Russell 2000 Value with a basket of only ~150 stocks.

This formulation of small cap value is exactly inline with my 2020 paper, “Talking Your Book About Value” (the original source of pissing Cliff Asness off, btw) which hypothesized and demonstrated that the small cap value premium could be modeled as a series of option contracts created by the portfolio construction rules. Under this theory, small cap value is almost exactly Rob’s formulation — “Small cap value portfolio managers agree in advance to buy what falls and sell what rises.” This means they are short calls and short puts, ie short volatility. If we look at the history of performance of short volatility strategies, it looks an awful lot like the return to Value vs Growth:

Comparing the R2000V vs the NIXT index, we see that they are largely identical with two notable periods of exception — 1997-1999 and 2020-2022. These are two periods where put sellers were unquestionably bailed out by the Fed, suggesting that my hypothesis may be even more true than I had suspected. It also raises the question whether NOW is the time to be buying these indices with short volatility priced relatively cheaply.

Finally, I was encouraged by some of the dialog in this piece. Arnott explicitly acknowledges that passive DOES trade, that they are NOT passive; he drops the ball by referencing index reconstitution rather than simple inflows, but this is huge progress. We need advocates like Arnott to start fighting back (and to have Cliff join the fight). Unfortunately, Rob’s not QUITE ready to do so, but it’s clear he’s close.

The Main Event

Sometimes, I just don’t want to write… and this week has been one of those times. I have to confess to being disappointed at hearing absolutely nothing from Cliff Asness. I really did try. Maybe he’s just waiting for part two. Fortunately there was a moderately complete draft in place, so without further ado let’s jump into the final two hypotheses that Cliff Asness offers to understand a decline in market efficiency.

In Part #1, we addressed Cliff’s hypothesis that “social media” was driving markets to become less efficient by “breaking” the wisdom of the crowds. While I completely agree that the breaking of the WoC is a critical insight and have been using exactly this model to demonstrate how the growth of passive can lead to “broken” markets, Cliff’s proposed mechanism is wanting in “endowment.” It may be true that social media is leading to uniquely inefficient behavior in investing markets due to “crowding”… but if this is true, it is UNIQUE to investing. We see no such evidence in other areas — in fact, fracture is the name of the game in all areas where social media has influenced society. And even if it were true, there is no mechanism for FUNDING these investment behaviors. What we KNOW to be true is that a subset of “professional” managers do receive billions of dollars a day to pursue systematic index investing strategies that absolute coordinate and direct flows — we call these passive funds. Why there is debate about whether Roaring Kitty can influence prices while insisting that 1000x more capital flowing into market index funds apparently does not is beyond me.

Hypothesis #2 – Very Low Interest Rates for a Very Long Period

Both Cliff and I agree that low interest rates are not to be blamed. I might frame it slightly differently, but we generally agree. The most simplistic theory of valuation provides a very straightforward link between valuation and interest rates:

Present Value = FCF/(r - g)

All else equal, lower interest rates and the Free Cash Flow multiple goes up. Congratulations, you just completed intro to corporate finance. But it’s not that simple… Once again, option theory holds the key:

Put-Call Parity: Stock = Call - Put + PV(Divs) + PV(Strike)

Note that now we have a slightly more complicated relationship… Why? Because Part 1 of this equation, “Call - Put”, has a NEGATIVE relationship with interest rates. All else equal, higher interest rates LOWER call values and RAISE put values, so [Call - Put] is negatively correlated with interest rates. We also have an uncertain relationship between interest rates and the PV of Divs… “Does the hiking of interest rates raise or lower the present value of dividends?” Well, if interest rates are hiked because inflation is raising the value of dividends in nominal terms, it’s unclear. The ONLY clear relationship is with the PV of the strike. As a result, it should surprise no one that there is an unstable relationship between interest rates and equity prices:

And yet, there IS a puzzling large relationship between interest rates and equities even as we acknowledge that the theoretical relationship is uncertain. And there we discover what is the more likely relationship — bond and equity prices are often determined in a cointegrated manner at the portfolio level.

I’m sorry, please speak English….

OK, I’ll try. The traditional model of asset price formation is that information flows determine buying and selling. Imagine an equity manager evaluating AAPL vs MSFT and constructing a portfolio of equities first, then doing the same for bonds. Since AAPL and MSFT both have same underlying risk free bond exposure, my evaluation of the two is strictly determined by my forward DCF projections. The Fed is “free” to set rates at whatever level it would like and I am free to buy as much or little of AAPL and MSFT as I would like.

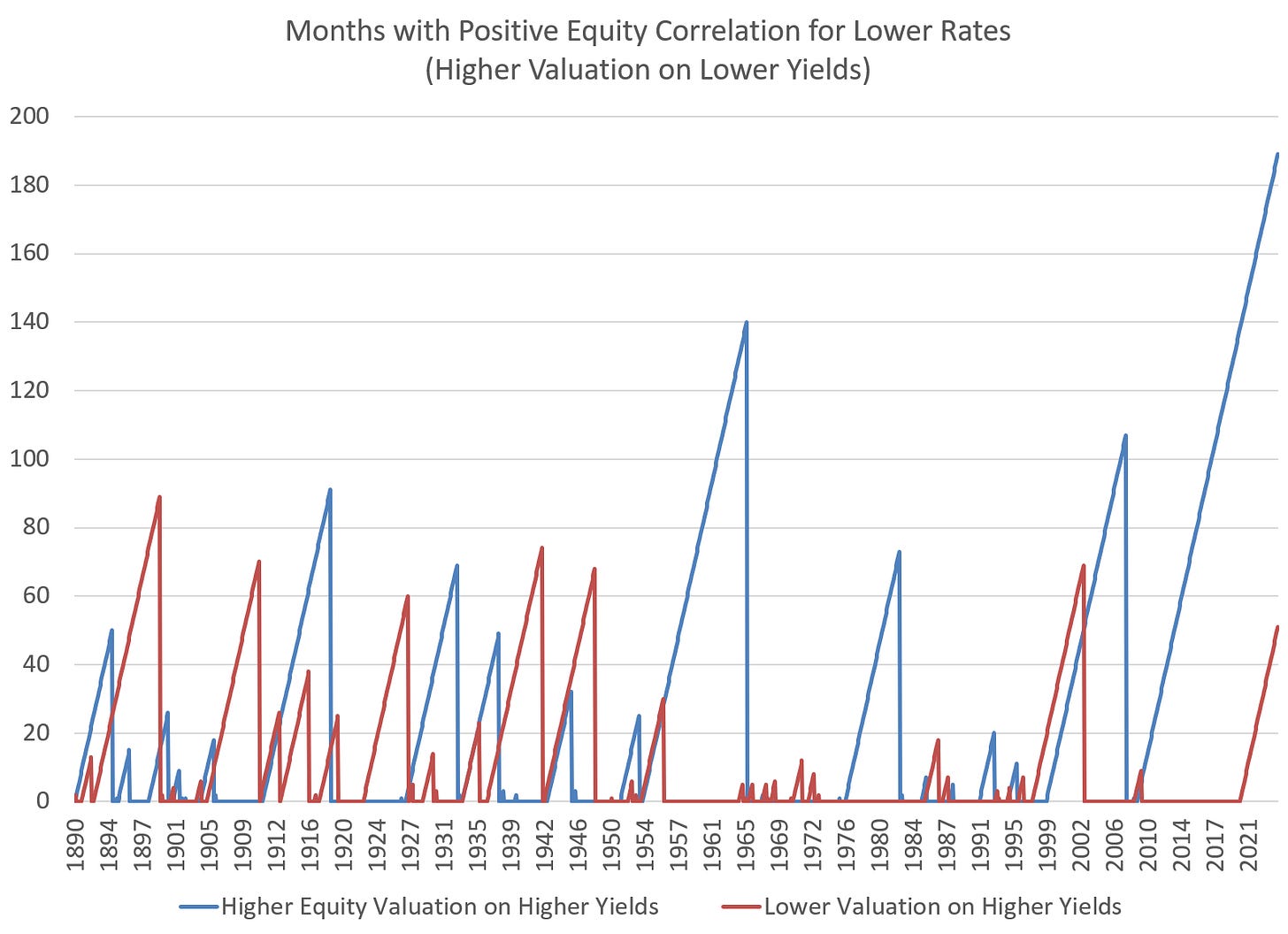

Now, imagine you have a portfolio that is 60/40 equity/bonds. If the Fed hikes interest rates, my bond portfolio most likely falls in price. I now own less bonds in $ terms than I would need to maintain my 60/40 weights. How do I proceed? Well, I sell equities and buy bonds. Rinse and repeat. Nowhere in the process was there a DCF or an analysis of AAPL vs MSFT and overall the price behavior remains — higher bond prices leads to higher equity prices. This has REMAINED the underlying correlation for bonds and equities even as headlines are raised about a negative correlation. If I separate monthly price performance into “higher rates” and “lower rates”, the change in valuation for the S&P500 on lower yields (higher bond prices) has remained positive for a record number of months. While many headlines have been written about the change in correlation between equities and bonds, the unfortunate reality is that it hasn’t really changed — the Fed just decided to hike too many times too fast, leading to a perception that the correlation had flipped.

How can this happen? Well anytime you have a portfolio allocation, you will find that one price helps to determine the other. Thus the “portfolio rebalance” channel as outlined by Jonathan Parker or Xu Lu. These papers suggest that between 50-70% of the reaction function of equities to monetary policy is now flowing through this channel rather than through any attempt at modeling discounted cash flows. As a result, we can’t BLAME the mania on lower interest rates (or monetary policy)… but we can acknowledge that Fed interest rate policy that inflates the value of bonds will (all else equal) inflate the value of equities.

Hypothesis #1 – Indexing Has Ruined the Market

Let’s start with the good news: Markets are LARGELY efficient. The “best” companies, as measured by profitability and growth, are typically the most richly valued. Growth expectations impact valuations. This is to be expected in a market still influenced by active managers “doing the work” of assessing the value and prospects of individual businesses. To my knowledge there is no mechanism for passive investing to make this happen without active managers.

However, markets are getting LESS efficient over time in a practical sense. Volatility on fundamental events is growing larger, correlations between securities in indices is growing stronger, and valuations are getting increasingly at odds with traditional theory:

The impact of passive is to inflate ALL valuations, but those of the largest stocks more. Hence Cliff can be right that the “value spread” is rising (affected by the most expensive stocks getting an extra boost) AND it’s possible that “value” is not cheap, contributing to the frustration of value investors. Why would it affect the largest stocks MORE? Because these are the LEAST elastic stocks — they cannot be substituted or replaced in any market index. I can choose to statistically sample the index… I can even exclude some of the smaller companies and “take a chance” on tracking error… but I cannot exclude the largest stocks. In the simplest terms, this means the largest stocks ARE biased upwards versus their smaller peers.

Add to this phenomenon the “relentless” bid from passive. Remember they are NOT passive because they transact (every day on inflows). So they are actually super simple algorithms — “Did you give me cash? If so then buy.”

At what price? Whatever price was last available! Does the incremental buying impact prices? Of course! Bouchaud (and others) estimate roughly 50% of the Gabaix & Koijen multiplier gain persists each day… and inflows happen every day… And so prices get pushed up as passive gains share. Would prices ALSO rise on inflows into active managers? Almost certainly. This is not an attempt to assert that this is a UNIQUELY passive phenomenon. But because we’ve removed the valuation bias from active managers by replacing them with machines that have a momentum bias (buy whatever is up most), the markets no longer mean-revert in the same way:

This does not mean that large cap stocks cannot underperform or sell-off (although it occasionally feels that way)! It simply means that they have a positive drift relative to other stocks as passive gains share… and eventually, that impact from share gain becomes quite substantive. As passive share gets larger and larger, this drift becomes more pronounced because, as Valentin Haddad notes — passive is unwilling to change their market position on news. And this is where it gets really perverse, because the positive drift means that “alpha” for active managers slowly gets twisted lower. Why? Because “alpha” as a time-based construct is simply the intercept of a linear equation:

Portfolio Return = Market Return x Beta + Alpha

y = mx + b = βx + α

And, unfortunately, this narrative perfectly matches the observed data:

Is it possible that ALL of this is is a coincidence and it simply turns out that active managers have gotten far worse at their jobs? Yes, it’s theoretically possible. But when we cannot find a single fact that deviates from the passive-driven hypothesis, perhaps it’s worth seriously considering that “Yes, indexing has indeed ruined the market.”

Or, we could just shout at social media. Your choice.

“obviously you’re buying everything in proportion to its market cap and therefore you’re not changing anything.”

This statement has an implicit assumption that liquidity scales with market cap.

Because this is not true, and the biggest stocks get the biggest passive inflows, the biggest stocks tend to rise the most over time and they become much more volatile than the mid caps.

I’m just simplifying your argument here, feel free to let me know if I missed something critical.

Mike, your work on passive has been really eye opening for me. I think your effort to bring awareness is admirable and will hopefully make its way to better policy making (fingers crossed). Regardless, you make the concept easy to understand, which should help spread the word and get the right people thinking about the potential ramifications of passive selling.

One question to ask though…how much has passive affected major European and Asian equity markets?