We Have Met the Enemy And They Are US

Imagine the world of the 1920s from a European perspective against the US export juggernaut and you'll get a glimpse of China

Summary:

Economic Dominance and Global Power Shifts: The US and China currently dominate the global economy, holding 43% of global GDP, reflecting a concentrated economic power not seen during the pre-Great Depression era. The global focus must be on China, whose demographic challenges and increasing authoritarianism are shaping its domestic and international policies.

China's Domestic Challenges and Global Trade Impact: China's aging population is leading to diminishing internal returns and aggressive external trade policies. The country’s economic strategies resemble historical patterns seen in the US and Japan, risking global trade tensions and economic instability.

Historical Parallels and Strategic Choices: China’s current trajectory mirrors past economic peaks and declines, such as those of the US in the 1920s and Japan in the 1980s. The choice between aggressive global expansion or stabilizing domestic investment will determine whether China can maintain its economic power or face a significant downturn, potentially dragging the global economy with it.

Top Comment

Neely Tamminga chimes in from the land of a thousand lakes:

As ever and always, thank you for the gift of insight. The older I get, the more I appreciate a well-crafted sentence, a cogently chosen paragraph, and a succinct word. Appreciated specifically the one-sentence homily, “What we have so far is good old-fashioned “work harder to keep your job,” a classic recession indicator.” That sentence alone could preach a sermon.

Enjoy presence with your son!

MWG: Thank you, Neely! For those that don’t follow her on Twitter, @NeelyTamminga is a former sellside retail analyst (meaning she followed retail, not selling to retail) who has transitioned into entrepeneurship and academia. She’s a thought leader on Twitter and I’m always flattered by her interest in my work. Make sure to check her out!

The Main Event

On the eve of the Great Depression, the US economy was easily the largest in the world, running a GDP of roughly $850B against a global GDP of ~$8.5T. This relatively tame 10% for the global leader seems bizarre in the context of the current race between the US and China, where the US generates 26% of global GDP and China generates nearly 17%. In US$ terms, 43% of global GDP is concentrated in two countries. Let that sink in for a second. This is the world in which we evaluate the threat of trade tariffs.

The world is currently very focused on China, for its demographics trap it. The population is now falling, and the working-age population has been falling for over a decade. An increasingly authoritarian regime is necessary to maintain the aims of the state. To be clear, this does not imply the regime is increasingly unpopular. After all, Winston loved Big Brother. And direct surveys of the Chinese people show the policies of the government are wildly popular:

A relatively recent paper from the China Quarterly challenges this assumption, using indirect methods of list-ranking to establish an estimate of the degree of repression in results. The LOWER limit is that Beijing’s regime results in opposition being understated dramatically:

When respondents are asked directly, we find, like other scholars, approval ratings for the CCP that exceed 90 per cent. When respondents are asked in the form of list experiments, which confer a greater sense of anonymity, CCP support hovers between 50 per cent and 70 per cent. This represents an upper bound, however, since list experiments may not fully mitigate incentives for preference falsification. The list experiments also suggest that fear of government repression discourages some 40 per cent of Chinese citizens from participating in anti-regime protests.

Unfortunately for China, it’s not just its own citizens who are increasingly frustrated with the CCP. Growing opposition to CCP trade policies are likely to prove the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Like the US in the late 19th century, China has reached a point of diminishing returns to internal investment and consumption and therefore is dumping its excess production on the global stage in the hopes of staying one step ahead of the debt collector. Like the malinvestment that occurred in the US in the 1920s, when excess production was created to help fight WW1 and rebuild Europe in the interwar years, China will find itself with far too many goods and far too few markets. It is hard to see the malinvestment itself as inflationary — and as I’ve highlighted repeatedly, consumer durable goods prices are falling at rates not seen since the 1930s; but if the attempts to balance global trade turn openly hostile, then the costs will inevitably turn higher.

The US as Precursor

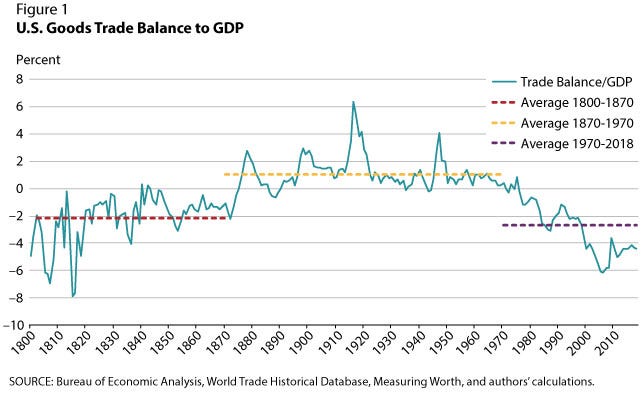

Back in 2019, a period we’ll call “The Great Before”, the St. Louis Fed shared an analysis of US trade deficits over time. It noted that the developing US ran persistent trade deficits as infrastructure development consumed the majority of US economic activity. Almost immediate after the Civil War, the US shifted into perpetual trade surplus that ultimately grew to 6% of GDP at the end of WW1, but persisted in positive surplus until the 1970s. As the St. Louis Fed put it:

“Historically, industrialization has three phases: (i) the first industrial revolution features labor-intensive mass production, (ii) the second industrial revolution features capital-intensive mass production, and (iii) the welfare revolution features mass consumption in a financial services-oriented welfare state…

Since the 1960s, the United States has shifted to the welfare stage, featuring mass consumption with financial innovations. This shift implies that the United States became able to consume more tangible goods than it produced by providing financial services to the world. During the early 1970s, the U.S. trade balance experienced another inflection point—from trade surpluses to trade deficits—as U.S. financial assets became more attractive to foreign investors. Again, this shift also corresponds with a structural change in the economy as the United States entered the third stage of industrialization.”

The US sanctions on Russia heavily damaged this somewhat benign interpretation of US trade deficits; who would trust the US as their financial service provider when its banks seize your assets in times of stress? The US policy for short-term gain against long-term principles has unquestionably led to the emergence of the BRICs currency movement. To be very clear, I do not think the BRICs concept is legit. As I have repeatedly emphasized, the center of an empire MUST consume; it cannot produce. Otherwise, you will be perennially forcing your customers to consume at gunpoint… a policy that can work for a short time but ultimately proves insanely costly.

Japan faced a similar dilemma in 1989: its increasingly productive workforce and rapidly slowing population combined to generate surging trade surpluses. The real story of the late 1980s was Japan’s acquiescence to US military and political might. Japan was incapable of the reciprocal of Commodore Perry’s forced opening of Japan’s markets in 1853 under threat of Western military might. When George Bush vomited on Miyazawa in 1992, it was not gastroenteritis… it was because he could. Since then, Japan’s trade surplus, like the US before, has inexorably shifted into trade deficit. It is likely to remain in structural deficit for the foreseeable future even as periods of relative yen weakness occasionally push it into surplus, as we’ve seen for the past few months (an unappreciated source of yen strength IMHO). Japan’s GDP, which peaked at nearly 18% of global GDP in US$ terms (rather than PPP), has now fallen to a mere 4% of global GDP. It is a brilliant and highly talented country, but like the UK has largely fallen into present-day irrelevancy:

While Japan has increasingly turned to importing foreign workers to fill its domestic labor shortage, these workers, like the Germanic soldiers in the Roman army, will eventually turn Japan into something quite different — regardless of how politically incorrect it is to say so. Multiculturalism is hard, even when you’ve got a giant continent to fill. Adding an aging population to an island is going to be quite a challenge. Expect to see more of these articles: