The Remains of the Day

We just got our last pre-banking crisis jobs report... how might the data change going forward?

Despite the market being closed for Good Friday/pre-Easter/Passover holidays, we got the release of job market data. With better-than-expected data, I felt it was necessary to offer a brief insight:

A monthly jobs report that comes out on April 7th does not capture all the data in March despite the label. The official methodology from the BLS is that the period surveyed must capture the pay period that includes the 12th of the month. So technically, those who lost their job in the immediate aftermath of the Silicon Valley Bank failure could have been captured. At least we’d see the SVB employees hitting the tape… right?

OK, the point is made — this employment report, deeply flawed on its own merits for reasons I have highlighted repeatedly (Birth/Death, response rates, etc), has no relevance for the post-bank failure world due to data timing. In the next report, May 5th, we’ll see the first indications of the impact of credit tightening on the US employment market. Patience is a virtue.

The rates markets are showing no such caution. After the report, the 2yr rate jumped nearly 15bps, undoing nearly a week of gains:

And for all the hoopla about markets aggressively pricing a Powell cut in the second half of 2023, the yield curve spread for the “official” recession metric introduced by Cam Harvey, the 10y less 3m, has become more inverted than any time in the past forty years. Even relative to Volcker’s cycle, the levels are impressive:

Simply put, these levels of inversion do not last long, and the history of them being resolved without a cut from the Fed is basically zero. As we saw in the mid-1970s experience, however, it’s not as straightforward as simply buying the 10yr bond — in about half the normalizations, 10yr bonds do not rally. In fact, the recent experience of 10s rallying post-normalization is the aberration rather than the norm. This makes me cautious in assuming 10s (or ultras) are the place to be for this cycle.

The inability of the Fed to push through its rate hiking cycle without a deep inversion occurring from low absolute levels of interest rates should have been a warning sign, but it was ignored. Instead, we set off on a quixotic quest to obtain rear-view mirror positive real rates, almost unquestionably driven by false narratives like the Stan Druckenmiller statement, “Once inflation gets above 5%, it's never come down unless the Fed Funds rate is higher than the CPI.” This has contributed to the (false) perception that the Fed remains accommodative even as interest rate-sensitive sectors have cratered.

The uncharitable (and preferred) interpretation is that Powell et al. mean well but simply don’t know what they’re doing. The charitable interpretation, again not my preferred as it would require government regulators to play 3D chess rather than Chutes & Ladders, is that the government is trying to “liberate capacity” (read, “causing unemployment”) to accomplish government objectives. Namely, war.

But let’s not let distract ourselves with Orwellian fantasies and instead endorse Hanlon’s Razor — “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity” or, as I like to paraphrase it, “Never assume conspiracy when incompetence will suffice.” Forgive them; they know not what they do.

The issues are further complicated by the changing characteristics of the labor market. As we’ve discussed in prior notes, the key change in the labor market has been the absolute decline in the number of potential workers with less than a Bachelor’s degree. As shown in the below chart, since the GFC, the number of workers in the labor force with less than a college degree (yellow) has fallen by nearly 7MM workers even as the aggregate labor force has grown by 13MM (white). The obvious driver? Growth in the college (or higher) educated labor force of nearly 20MM — nearly 50% in just 15 years.

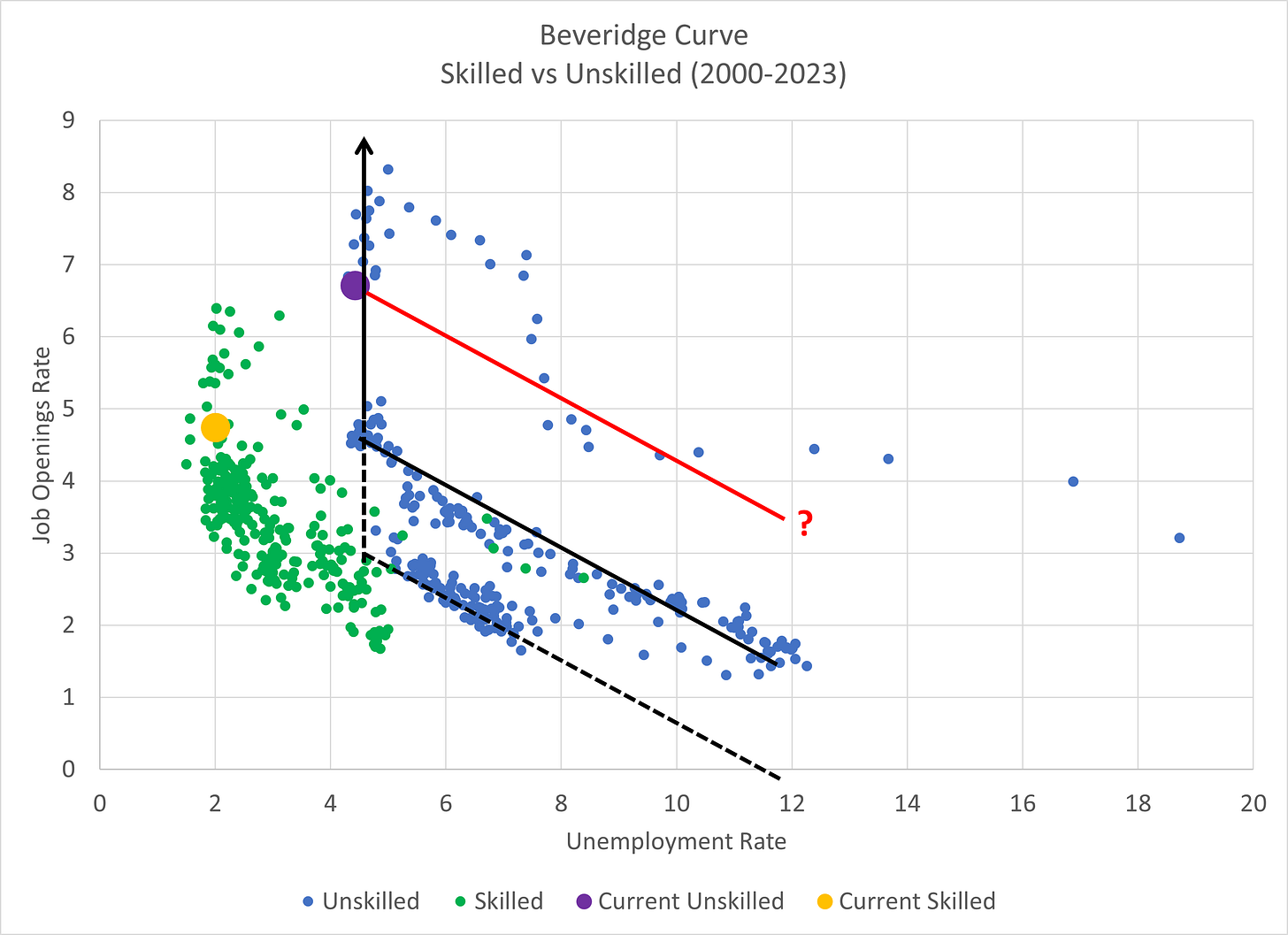

The relationship at the heart of the Phillip’s Curve (that much debated model that sits at the core of the “we have to raise unemployment to slow inflation”) is actually a second curve, the Beveridge Curve. The Beveridge Curve is named after William Beveridge, a contemporary of John Maynard Keynes and the foremost thinker on unemployment of his day. Unlike its better-known cousin, which presumes a relationship between unemployment and inflation through a flawed cost-push model, the Beveridge Curve is a relationship between job openings and unemployment. The distinct characteristic of the Beveridge Curve is its ability to identify the “vertical” portion of labor supply that occurs at minimum unemployment:

The relationship between job openings, as proxied by the NFIB’s excellent small business survey data that has been in existence since 1973, and the unemployment rate is clear. Higher job openings (difficulty filling jobs) leads to lower unemployment rates. And the divergences from the curve created by disruptions like the Covid pandemic or GFC are also clear and fairly quickly resolved. Unlike estimates of the “natural rate” of unemployment that typified economic discussions of the 1980s and 1990s, there is no sign of a “vertical” shift in job openings required to indicate a lower limit to unemployment until 2007 when unemployment finally approached 4%.

“Truly you have a dizzying intellect.”

“Wait till I get going!… where was I?”

“Australia…”

Ah, yes… Australia… in 2003, a Chinese PhD student at Melbourne University postulated a Beveridge Curve segmented into “skilled” and “unskilled” by educational requirement. It’s a fascinating paper with a clear articulation that, “Yes, the curve is actually segmented.” Skilled and unskilled jobs are not interchangeable. A newly minted college-grad may become a barista… but things have to get pretty bad before a 45 year-old married engineering major becomes a barista. Likewise, no amount of job tightness in neurosurgery will lead to high school dropouts being accepted into the role. The key question that has yet to be addressed is where the “new” elastic point on the respective skilled and unskilled curves. This will hold the key to the question of what happens to unemployment in this cycle — if the unskilled curve has elasticity from this point, suggested as plausible by the Covid-cycle (red line), then unemployment will start to rise rapidly soon. If, on the other hand, the elasticity sits lower, then we could see unskilled job openings fall by another 2MM, nearly 30%, before unemployment begins to rise markedly. For those with a college degree, the news is less favorable. We appear to be within 500K job openings of unemployment beginning to rise for college grads.

“You’re just stalling now…”

“You’d like to think that, wouldn’t you?”

The educational attainment dynamic appears to be driving the vast majority of the “tight labor market” story. This suggests another risk. The falling number of potential unskilled workers suggests automation needs are mandatory. A similar story occurred with declining agricultural workers falling post-WW2. The impossibly low unemployment rates in the 1950s, a decade with unemployment averaging 4.5% and inflation running only 2%, set the stage for corporatization of American agriculture. While the US had been industrializing for over a century, as late as 1950 over 50% of US farms were owned by small farmers. Today, 85% of US agriculture is owned by large corporations. Surprisingly “un-PC” headlines from the New York Times highlighted the labor shortages as Mexican immigration temporarily filled the void:

This corporate takeover accelerated in the 1980s as small farmers found themselves burdened with equipment debt attempting to keep up with larger competitors taking advantage of automation. Remember Farm Aid?

This time around, it’s not agriculture but small businesses that need to invest to update and keep pace with the automation advantages their larger competitors are deploying:

While it’s a calculated metric as the data is not easily available in this form, small business is radically skewed towards hiring those with less than college degrees, while larger businesses, replete with the “necessary” HR/accounting/compliance departments are roughly 50% college-degree plus.

Segmenting JOLTS job openings into large and small businesses, we discover that the college grad employing large businesses are rapidly reducing job openings while small businesses, stuck trying to hire high school grads, have made zero headway in finding less-skilled workers.

This leaves small businesses uniquely disadvantaged in today’s labor market. Unfortunately, the BLS is convinced there’s a surge in entrepreneurship as Door Dashers file for EIN’s to allow payment via 1099s now that the rules changed to drop the 1099 threshold from $20K to $600:

If you believe that jump is rising entrepreneurship, can I interest you in a bridge for sale? Cheap!

“You’re trying to trick me into giving something away… it won’t work”

“It has worked! You’ve given everything away!”

How will these small businesses make these investments with regional and community banks, their traditional go-to for financing, facing rapidly rising costs of funds? The answer is, “They won’t.” Instead, like small farmers, they’ll slowly disappear. Your local sandwich shop will become a Panera. Lucky ewe.

This suggests this cycle is likely to be characterized by high levels of small business failure, further consolidation, losses on small business lending, and the ultimate replacement of their workers by automated competitors, much like we saw the corporatization and automation of agriculture. It’s a reasonable template. Instead of cash register operators, we’ll have much more highly compensated kiosk repairpersons and app developers. But there will be far fewer of them, and they’ll likely work for much larger organizations.

The robots are coming. It’s just a shame that we’ve raised the barriers for small businesses to afford them and simultaneously robbed our communities of much-needed vitality. The picture is not one of entrepreneurship but of rising corporate servitude. Hug your local small businessperson… they’re gonna need it.

As always, comments are appreciated.

The last operating business of our family office corporation was liquidated at the end of 2022 because of the restrictions imposed in California in the name of the Covid public health emergency. Thanks to its automated systems, the business was able to survive on the reduced revenue from small business customers who had also survived the shut down. But, the business could not afford to pay returns to the people who did the work and to us as the owners for the work and money we owners had invested in developing the automation. So, we transferred our shares to the "workers". They were our friends and economic partners, and their only capital was their ability to run the business. We had the money we had saved from the business' profits.

It was hardly an act of charity. If we had "laid off" the workers in hopes of squeezing out a few more months of profit, California's unemployment insurance rules would have swallowed that small amount; and we would have had the legacy liabilities that Donald Trump's "You're Fired" dramas never bothered to mention.

"Automation" in the genuine sense of machinery and software and workflow designs has not been a choice for businesses of any size since microcomputers and bar code scanners learned to talk to one another. They reduce to unit costs of production by an order of magnitude. That fact of life is not yet apparent to "large" companies because their returns on capital is subsidized by the passive investing system that Mr. Green has so elegantly explained. But, for "small" businesses there is no longer any possibility of paying for both investment and labor. That is why no one opens independent sandwich shops and Subway limits its franchise offers to "multi-unit" operators.

Where I live the only good sandwich shop went out of business 10 years ago, but point taken. It's like what Russel Napier is fond of mentioning, access to credit will be the factor that determines success in the coming years.