Resending: "Well now you're just making stuff up..."

Just the non-facts, ma'am!

My apologies for the possible resend. Mrs. Plum informed me that I apparently sent this edition ONLY to those who had subscribed directly through Substack. If you’ve already read, my apologies for the resend as well as any part of the note you found poorly researched and unconvincing. We all know that’s basically all of it. Regardless, thank you for your patience as I learn the platform.

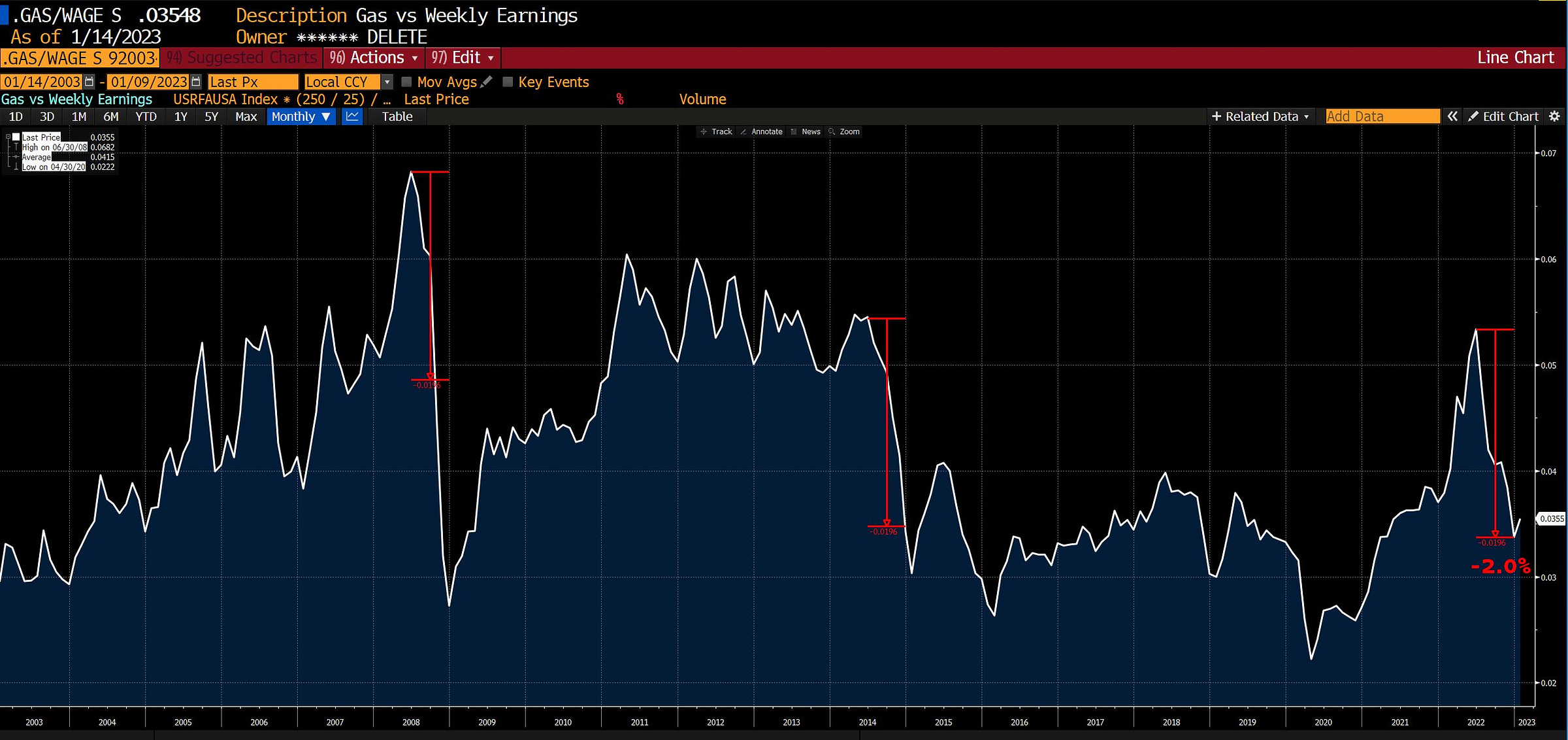

Last week’s post appears to have resolved many questions on my oil demand model. One final comment on oil — I focused on demand because that is where a “macro” investor can add value to the oil discussion. If I was unclear, I’d reiterate that oil investors will “barrel count” far better than I ever will. Rely on them for supply. And the fundamental story in oil IS primarily about supply. The introduction of fracking/shale in the United States introduced a sizeable marginal provider, but unlike the giant oil fields in history (Gawar, etc.), these fields have rapid decline rates and need to be replaced quickly by new wells. As many on the barrel counter side have noted, it will be challenging to maintain production. But I continue to emphasize, “Demand is more elastic than you think,” and one of the hidden stories in the reacceleration of the economy in the last two quarters has been about declining gasoline prices which have added roughly 2% to household spending potential. This is similar, although slightly less than the “stimulus” received from falling gasoline prices in 2014 and 2008/9. It’s slightly larger than the stimulus in late 2018. In my opinion, it is very welcome, but ultimately not enough to prevent an incipient recession. If the oil bulls are correct, and that little uptick on the right suggests they might be for a while, that tailwind could turn into another headwind.

“I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time -- when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what's true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness...” — Carl Sagan, 1995

There were lots of comments on luck. One of the most common was, “Yes, luck plays a significant role, but the harder I work, the luckier I get.” This is very true. I have been very lucky, and I have worked very hard. Since I was about ten years old, I have been waking at ~5 am to either swim, commute, study, or work. I also had people make many sacrifices to improve my probability of success. My parents did not have to offer me a superior education, but they did. My mother, in particular, made a Herculean effort to provide me with educational enrichment, including volunteering her very limited time to work as a docent at the California Academy of Sciences so I could take discounted science classes during summers and weekends. I’ll never be able to repay her. But she could not have provided those resources on her own, and again, I was VERY lucky.

The year before I was born, a little revolution in childcare kicked in. In 1969, PBS (yes, the Public Broadcasting System) introduced a series of educational programs designed to offer an alternative to children’s cartoons. The most famous was Sesame Street, known for its Jim Henson characters, “The Muppets.” But what is less well remembered were the lessons that even today I cannot forget — set theory (“One of these things is not like the other”), the alphabet (“The Lonely ‘N’”), number theory (“What is the number of the day?”), tolerance and empathy (“Oscar the Grouch”), and loss (“Mr. Hooper’s final scene”). Among the many other expenses my parents couldn’t afford, but bore, was a 23” color TV, which likely cost them close to 10% of their household income, but enabled me to absorb these lessons thoroughly. Something to keep in mind when we decry hedonics.

Likewise, as I approached the age of reason (seven is the traditional metric), the California Academy of Sciences introduced “The Discovery Room,” modeled on the recently opened children’s center of the same name at the Smithsonian (1974) and extensive weekend and summer classes for the children of San Francisco. Conservatively, between 1978 and 1983, I’d guess I spent well over 1,000 hours in the Discovery Room (again, where my mother worked all day Saturday so I could attend for “free”) and associated classes. By the time I hit high school science classes, I was so far advanced that my freshman-year biology teacher handed me a textbook and the AP test and said, “Go.” The same thing happened for chemistry and physics, and as a high school junior, I considered skipping ahead and simply heading to college. But none of this was possible without a societal investment.

Had I been unlucky enough to be a child today, I’d discover that the Discovery Room is now closed. Weekend science classes are no longer an option. In exchange, I can download as many Youtube videos on science as I want. This is not progress. In a city (San Francisco) that is supposed to be the world's technology center, we’ve moved backward over 40 years, and it’s become harder to offer the resources my mother made available to me. Carl Sagan’s dark vision is becoming a reality as “Science” (capital S) replaces the scientific method. But how about those 49ers? Have to make sure the gladiators are playing.

Is there a solution? I don’t know. But the reason the Discovery Room worked is that society committed to children. Parents volunteered, and donors donated. Three years into the ultimate Boomer act of selfishness, perhaps it’s time for another rebirth. On that subject, I’m looking forward to my first “author discussion” session NEXT Sunday(January 22nd) at 6 pm PST with Richard Duncan, whose book “The Money Revolution” I read with interest. The Zoom link will be mailed to registered readers on Monday and again Sunday morning. Feel free to share, but attendance will be limited by my personal Zoom license, so try to be early. It will also be recorded and available for replay on this Substack. We’ll turn this into a regular feature if there is continued interest.

Richard’s book asks, “What do we do with the power that MMT grants us?” If you’ve listened/read my commentary for long enough, you’ll know that I believe MMT is “true” and descriptive of the system we have in place, but not prescriptive (“What should I do?”) or proscriptive (“What should I not do?”). I think sovereign (fiat) debt is more equity than debt. You cannot default on fiat debt in your own currency, just as you cannot default on equity in finance. But you can make both worthless through poor policy choices or flawed execution. Unfortunately, 2020-2022 (and likely 2023-2030) appear to be poster children for both mistakes. So what SHOULD we be doing, and what are the risks? Again, read Richard’s book and join me for a discussion next Sunday. The answer is not to “pay people to dig holes in the ground and then fill them up.”

Over the last year, I feel like I’ve heard every possible comparison of the current economic and market cycle:

“It’s the 1970s all over again!"

“It’s 2000 to 2003 with the Dotcom bubble!”

“It’s the 1920s”

“It’s the 1930s”

“It’s the 1940s, you moron!”

“It’s the Fourth Turning”

I’m as guilty as the next person in seeking these analogs, and I’d propose, somewhat tongue in cheek, that the closest analogy remains the period following the Roman Social Wars and the rising threat of Mithridates in the East. Why tongue in cheek? Because it’s obviously not a reasonable comparison, given dramatic differences in standards of living, education, etc. But it does speak to a changing world order that began to chafe under the loosely enforced Roman hegemony. And it speaks to the rising stochastic threats that face the American Republic. What do I mean by “stochastic” in this context? Chance… luck, if you will. There is no reason America has to face the misfortune of an ambitious young king in the East laying claim to formerly American vassals. But it certainly does seem that forces are conspiring to introduce challenges. Whether it’s the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, Comrade Putin, or Xi the Magnificent, the world currently sees no end to ambitious men (and they are almost always men) trying “breakout” strategies as America turns inward.

Along similar lines, an interesting paper came out recently by my friend, Roni Israelov, formerly of AQR. In this paper, Roni challenges the consensus thinking around diversification, noting that the traditional models of diversification fail under sophisticated testing. He notes three primary reasons why a 20-35 stock portfolio fails to diversify:

Idiosyncratic risk compounds over time: while diversification lowers the exposure to idiosyncratic risk, idiosyncratic risk remains significant and over the life of a portfolio the idiosyncratic risk compounds to again become the dominant feature

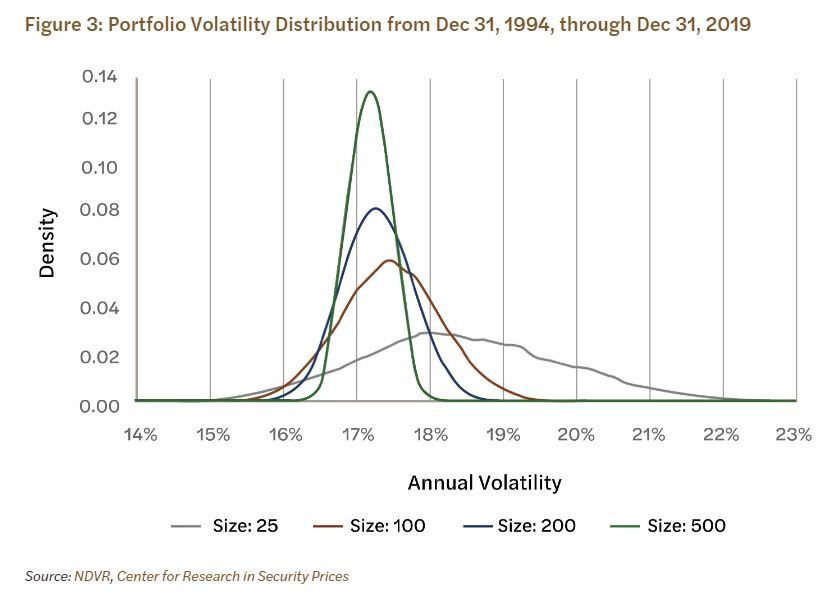

The distribution of risk matters as much as the average. Note the wide range of portfolio volatility for smaller stock portfolios from Roni’s paper:

Luck! (there’s that word again) As Roni puts it:

“We might not know in advance which stocks have high average returns and which have low average returns, but that doesn't mean they are in fact the same. Imagine a coin toss that determines each stock's expected return: heads and the expected return is 12%, tails and the expected return is 2%. But we don't get to see the coin. From our point of view, the stock's expected return is 7%, but, in reality there's a 50:50 chance it's either 2% or 12%. And because individual stocks are so volatile, it's nearly impossible to identify which stocks fall into one category or the other. We might get unlucky in our selection of 20-30 stocks and pick a portfolio of stocks that flipped a bunch of tails.”

Now Roni has chosen to illustrate this with individual stock portfolios, but I’d suggest the same observations extend to the S&P500 and illustrate another important reality — “We don’t know.” We don’t know what future growth is. We don’t know if the Fed will hike or lower rates. We don’t know if terrorists will attack the Twin Towers. We don’t know if a global depression will hit soon after we begin investing… or near the end of our investment careers.

An interesting exercise I recently conducted was to recreate the S&P500 by randomly sampling every day of returns and constructing a history of “alternate reality”:

Now remember, each of these lines has the exact same data points. Therefore, by definition, they begin and end at the same point, and each series has the same CAGR and standard deviation on a daily basis. But note that, thanks to the Great Depression, the actual data series is the WORST for a period of time. Bad policy and bad luck. Also note that one of the paths had nearly 100x the return of the worst path by the mid-1960s. Luck.

If we string together these identical days into more realistic time series, let’s say rolling 10yr periods, they are no longer identical due to timing luck:

So when we talk about “the expected return to large cap US equities”, let’s keep this in mind — we honestly don’t know what that is.

What are the implications of portfolio construction techniques that suggest we DO know? Well, we overweight the asset class due to perceived certainty. Note the aggregate payoff to each sample results in a picture that looks like an American football (maybe a rugby football to be more accurate). This “certainty” sits at the core of many errors, the most obvious being a DCF approach to equity valuation. Heresy!

No, really. It’s true. We actually KNOW that this statement is untrue:

Value of a Company = PV (Future FCF)

How do we know it’s untrue? Because the value of a company also has to consider the embedded option value. A live company always has options available to it. “Do we buy back stock?”, “Do we make an acquisition?”, “Do we expand?” Those options must have positive value (an option cannot have negative value) and they cannot be reflected in deterministic cash flows. If we expand the perceived options, e.g. renaming the company with “Blockchain” or “Dotcom,” the valuation MUST rise, as frustrating as that may be to skeptical bears.

While this is obvious in theory, it’s oddly ignored by practitioners. As a result, we tend to undervalue options in the valuation process. It’s also underappreciated, in my opinion, by policymakers when they engage in extreme behavior (like hiking interest rates at an unprecedented rate). We’re currently engaged in a furious debate about whether a recession looms. Why? We can’t actually know until it’s in the past. So why does it matter?

It matters because a recession ends option value as conditions deteriorate. “Should I expand?” becomes “Can I obtain financing to continue?” And if you cannot, then you are worth less. Much less. 2023 is starting off with a bang. The S&P500 is up 4.2%. Small caps up 7.2%. “Junk”-rated equities are up 12.5%. Homebuilders are up 50% from their cycle lows (June 2022) despite homebuilder sentiment being in the toilet:

Perhaps markets know the answer this time. Perhaps thoughtful analysts have constructed accurate models, and thoughtful investors are diligently considering their holdings. Perhaps the economy is about to turn upwards, or the Fed will not be pushing on a string when it is ultimately forced to respond. Or maybe not. Maybe the Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY) craziness is simply telling us that these are more flows into illiquid markets.

Thank goodness for Sesame Street’s set theory and that 23” television. While there may be more to go, I’m leaning “none of these things is not like the other.”

As always, comments appreciated.

Mike - homebuilders give a good study on optionality. NVR only acquires land through options on those lots, and only exercises each option (on an individual lot) when they receive a deposit to buy a house on that lot. This strategy led to huge relative success for them vs peers in 2006-08 because they didn't need to write down the value of their land holdings as much (look at book value per share of NVR vs DHI & LEN over this period). Many builders have since copied their strategy and now control a substantial share of their land bank through options. This will help insulate them on any potential major downturn the next few years.

I’m from the Winky Dink generation. We put a piece of plastic on the tv and wrote on the screen...now I’m old and am writing on the screen.