People Are Crazy? Part 2

A rougher week for economic data makes the disinflationary case a bit easier, while making it confusing on a micro basis

Top Comment

Letushavepeace offered a contra-take in an exchange in the comments: "The longest yield inversion in history" is a statement that only makes sense if we limit "history" to the period for which there is ample data. The period following the Civil War had a yield inversion that lasted - depending on what rate estimates you choose for the shorter vs the longer maturities - until 1880.

http://www.tomsargent.com/research/PSHS_Bayes.pdf

https://people.brandeis.edu/~ghall/papers/PSHS_Method_20230602.pdf

MWG: This is a great point and is something I planned to introduce in Part 2. Briefly, a yield curve inversion is ALWAYS a sign of restrictive monetary policy. The period from 1872-1880 is known as The Long Depression and was largely a function of the exceptionally tight monetary policy required to return the US dollar "greenback" to gold backing.

LetUsHavePeace: I appreciate your genuine tolerance for the fat kid in the back of the class who won't put his hand down. The question of Greenbacks was settled at the end of Grant's first term. He had it literally rammed through Congress before the new members were seated. Hence, the Crime of 73. There was no monetary policy or Long Depression. Prices fell and relative wages rose, and immigration from everywhere exploded. I wrote a piece for X that should be published today - April 30 - that tries to explain why the curve inverted because of Grant's successful campaign. https://twitter.com/LetUsHavePeace1/status/1785280240534560792

MWG: Thanks for the feedback. Unfortunately, I’m going to have to disagree with you. The 1870s was a period of exceptionally tight monetary policy driven by the Resumption Act, which returned the US to the gold standard over a four-year period. The Crime of ‘73 was the end of bimetallism, squashing an arbitrage between cheap silver from the Comstock mines in Nevada and the official price of silver. Unfortunately, Western farmers, in particular, primarily relied upon silver (lower denomination than gold) as a wealth storage mechanism and the subsequent decline in the value of their savings relative to their debts contributed to a wave of financial distress in Western states.

The Resumption Act can be thought of as a Quantitative Tightening analog, although at a much-accelerated rate, especially relative to the growth of the US population, which LetUsHavePeace correctly observes surged. This surge was not driven by American opportunity as much as it was driven by a resumption of Civil War delayed immigration and the rolling waves of civil and economic distress occurring across Europe in the aftermath of the German and Italian unifications and the Franco-Prussian War.

The New York Fed has a nice piece on the Long Depression, and I like their acknowledgment that it has yet to be resolved whether it was entirely a monetary effect or due to a breakdown in the marginal productivity gains brought by the introduction of steel, rail, and steam to the United States:

The hard money view, with advocates in both political parties, moved Congress in the opposite direction of easier money with the passage of the Resumption Act in January 1875. The act required the Treasury to retire Greenbacks (currency not backed by gold) and committed the government to reinstate the gold standard in four years.

So, was the Long Depression just the industrial revolution peaking, with little that the government could do to offset defaults on a huge quantity of bad investments? Or was it unusually long because Washington pursued a hard money policy in the midst of recession in its quest to reinstate the gold standard?

https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/02/crisis-chronicles-the-long-depression-and-the-panic-of-1873/

The Main Event

The US economic surprise indices slipped quietly back into negative territory this week, making the case for disinflationary surprises a bit less controversial. While the general focus on inflation is tied to persistently sticky inflation, which hopefully we helped address last week, the “savior” of the inflation story on the short-term has been about recession and economic weakness. This week saw significant “progress” in this direction.

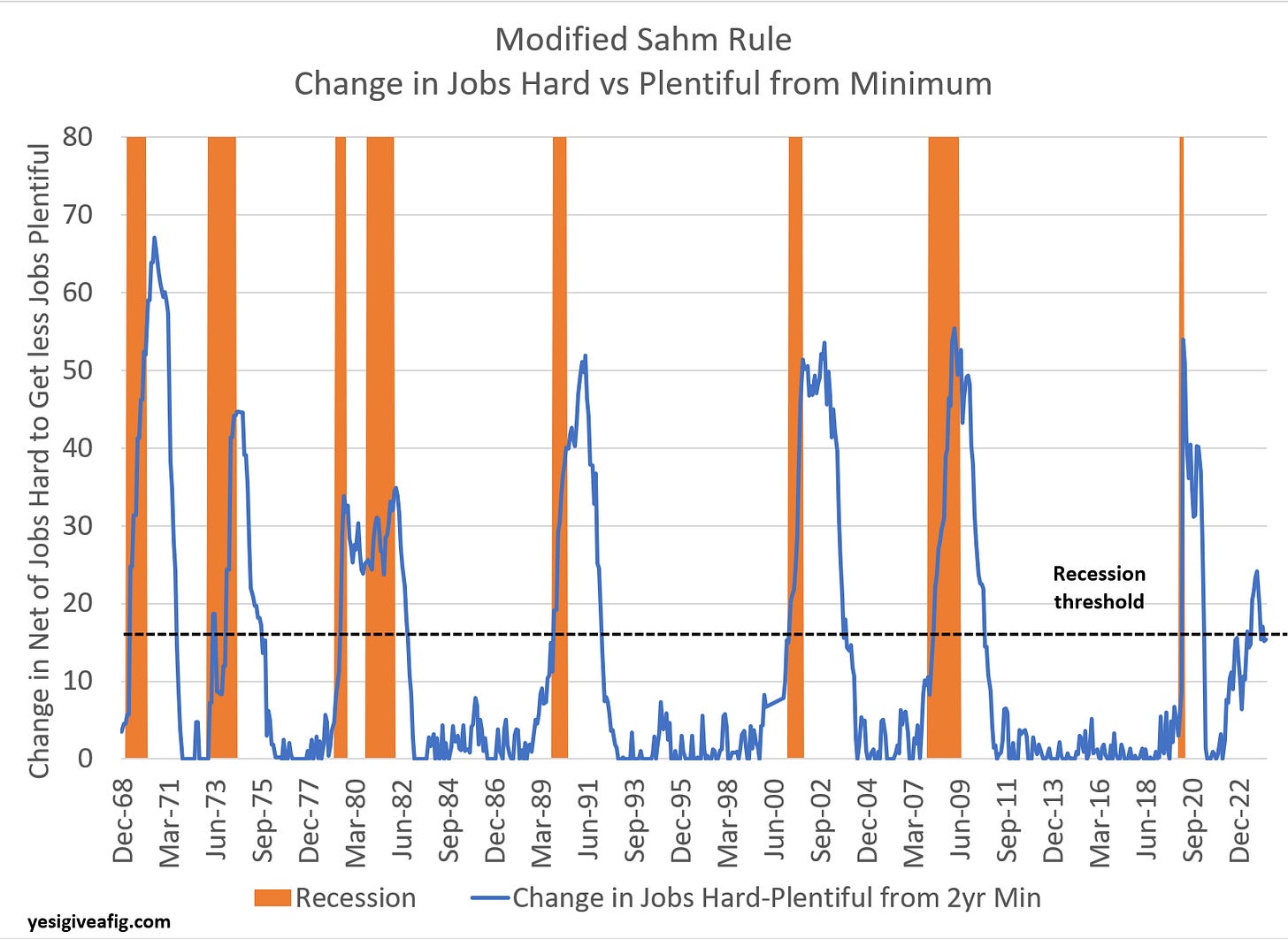

Not only did we see average hourly earnings come in weaker, the Conference Board’s “Jobs Hard to Find” vs “Jobs Plentiful” continued to deteriorate:

As we’ve highlighted many times, the Jobs Hard-Plentiful is one of many indicators that can be used to create a “modified” Sahm rule with fairly obvious conclusions. I will caveat that the halting nature of this lift from lows is somewhat unique in the history series and helps to understand the slow nature of the recognition that recession is almost certainly here.

Another strong indicator of economic slowdown emerged from the weaker than expected ISM reports. Once again, the reader is free to draw their own conclusions: