Pandora’s Ledger: Mispriced Hope

Non-linear tools of finance can explain why we've lost hope

When Pandora opened her jar, the poets say, she released every curse that would haunt mankind—greed, envy, sickness, decay. Only one spirit remained trapped inside: Elpis.

In Greek, Elpis means both hope and foreknowledge. That ambiguity has occupied interpreters for 2,500 years. If hope was trapped, humanity was left to suffer without consolation. If foreknowledge was trapped, we were spared the torment of knowing our fate.

The American experiment was built on uncertain hope—the belief that one’s birth need not determine one’s destiny. Citizenship itself carried an embedded option: a claim on the possibility of ascent.

Today, that option has decayed in value. Economists measure income, wealth, and inequality, but they have forgotten how to measure hope. They emptied Pandora’s box and replaced mystery with deterministic metrics—and in doing so, they mispriced the greatest asset ordinary Americans ever owned.

“I find myself increasingly impatient with those who despise patriotic ceremonies and traditions. Invariably educated and well-off, they have personal assets and achievements to be proud of. But most Americans are not so self-satisfied. Their proudest achievement is the freedom of their country; their most precious possession is their citizenship” — RR Reno, Return of the Strong Gods

The Invisible Wealth of the Working Class

The World Inequality Lab ranks the United States among the world’s most unequal societies. The data appear devastating: the top 1 percent holds nearly half of all wealth; the bottom half almost none.

But the charts omit an $80 trillion asset hiding in plain sight—Social Security and Medicare.

Every paycheck, American workers pay into FICA. These payments are not taxes; they are premiums on a state-backed, inflation-protected annuity. According to the Social Security Trustees, the present value of promised benefits is roughly $80 trillion—larger than the entire U.S. equity market. It is the collective balance sheet of the working and middle classes.

Yet inequality researchers exclude it because it is “non-marketable.” The rich own stocks; the rest own stability. Only the former count.

A 45-year-old with twenty years of contributions may expect a $30,000 annual benefit for twenty years of retirement—about $450,000 in present value for Social Security alone. Add Medicare (worth approximately $550,000 in lifetime benefits at current actuarial values), and this worker holds roughly $1 million in implicit wealth. On paper this worker’s net worth might be $25,000; in reality they hold a guaranteed trust fund underwritten by the Treasury.

When economists ignore this, they erase not just money but security itself.

Europe’s Floor and America’s Option

Europe guarantees pensions and healthcare, yet its system functions differently—and the difference defines the trans-Atlantic social contract.

Both European and American social insurance systems ultimately depend on political commitment and fiscal capacity. Social Security is not truly “property”—it’s a contingent claim subject to legislative adjustment. The Supreme Court ruled in Flemming v. Nestor (1960) that workers have no property right to benefits. If trust funds deplete, automatic benefit cuts follow under current law.

But the structures still differ meaningfully. European systems typically operate as pure pay-as-you-go transfers. American Social Security maintains the fiction of individual accounts and “earned” benefits tied to contribution history. This accounting architecture, while ultimately contingent, creates stronger political resistance to cuts—benefits feel earned rather than granted.

The real American distinction wasn’t ironclad security but rather how we combined a basic floor with institutional support for risk-taking: bankruptcy discharge (both personal and corporate since the 19th century), limited liability corporations, and liquid capital markets. Europe built a higher floor but with less upward volatility. America built a lower floor but with mechanisms to encourage and forgive entrepreneurial failure.

That combination—modest security plus institutionalized risk-taking—not the security’s legal structure, is what made American mobility distinctive.

Hope as an Asset Class

Hope functions economically like an option: a right, not an obligation, to move up the socio-economic ladder. Its strike price is the cost (in time and money) required to attempt advancement. Its underlying asset is the income differential between quintiles. Its value depends on both the probability of successful movement and the system’s permeability to effort.

In mid-century America, that option was valuable. A child born in the bottom quintile had about a 12 percent chance of reaching the top quintile. But more crucially, reaching Q2, Q3, or Q4 represented genuine success—a house, two cars, college for the kids, secure retirement. These middle rungs weren’t consolation prizes but the heart of American life. The probability distribution across all quintiles gave rational value to striving—it was the statistical foundation of faith.

Today, the probability of Q1→Q5 movement is about 7 percent. But the deeper problem is that Q2-Q4 have lost their luster, while the cost of trying to advance and the cost of failing in that attempt has exploded. Student debt became non-dischargeable as tuition soared. Acceptance rates at elite colleges plummeted. Geographic relocation now destroys family safety nets necessary for raising children with high housing costs, subpar public education, and high childcare and healthcare costs. The middle rungs no longer promise the good life that Q1 can strive for… and trying and missing means catastrophic debt rather than a second chance.

When mobility decays, hope decays with it. What remains is foreknowledge: the algorithmic certainty that where you start predicts where you end unless you win the lottery. Europe long ago traded uncertainty for stability; America is now making the same bargain and discovering that a life without risk is a life without hope.

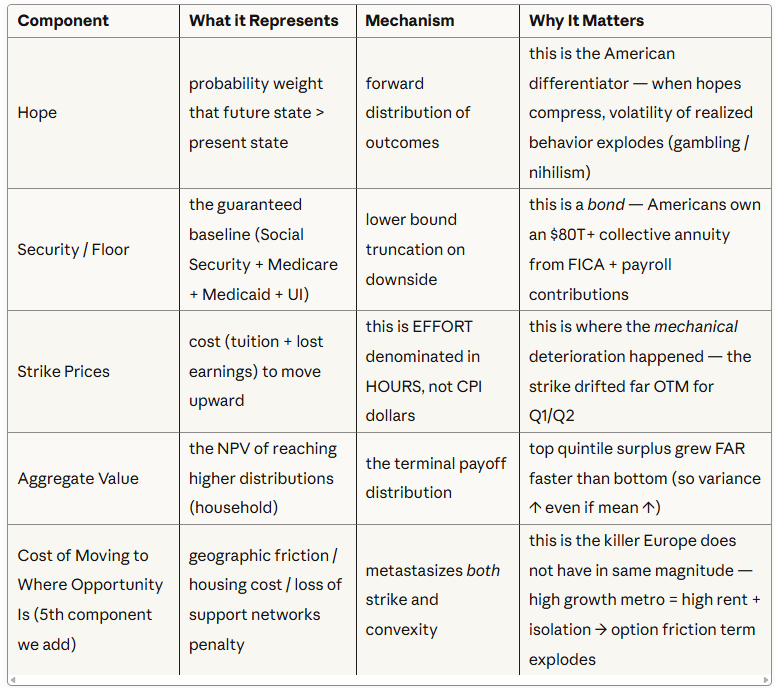

The Five Components of the Mobility Option

There are five distinct dimensions of American mobility, and each has deteriorated differently.

Hope — the upside convexity. The embedded call option in being born American: the belief that effort could convert into a higher future state. Hope in this framework is not mood — it is the call option on the expected value of shifting across socio-economic strata to the topside.

Security — the downside put. The protection from catastrophic collapse. Mobility only functions when falling is survivable. A society cannot rationally take risks when the left tail is lethal.

Strike Prices — the strike prices required to exercise the option to the topside. Historically, this was expressed mainly as access to land ownership; in today’s world, this is where education, credential inflation, prerequisites, and permissioning live. You can still have upside probability — and still have a near worthless option — if the strikes drift too far from your initial capability. Charles Murray frames the inability to advance as “poor choices” — but as we’ve often highlighted, GOOD choices are often a luxury created by initial endowment.

Cost of Moving to Where Opportunity Is — the geographic component of option decay. The high-productivity cities where upward mobility still exists have priced out middle-class entry through housing and child-rearing costs — and the move often destroys family support networks that formerly suppressed the left tail. This is the mobility tax that never shows up in CPI.

Aggregate Value — intrinsic surplus at birth + the call on upward mobility + the put against catastrophic downside – strike costs – mobility tax. This is the real economic value of American citizenship. The American Dream only worked when each upward move had positive expected value — when the payoff at each rung justified its strike price.