Ode to a Twitter Poll

“They were popular!

Please, it’s all about popular!

It’s not about aptitude

It’s the way you’re viewed”

Popular, Kristin Chenowith, 2003

Recently, I had the pleasure of listening to Jared Dillian on Dean Curnutt’s Alpha Exchange podcast. The recording can be found here: https://alphaexchange.simplecast.com/episodes/jared-dillian-editor-the-daily-dirtnap. In the episode, Jared notes he believed Bitcoin would dominate in an expected return poll. Roughly quoting Jared:

“In 2011, there was a poll for the best performing asset going forward. The answer was gold…. Gold was the most popular asset in 2011. Gold’s return for the next decade was -4% annualized. The most popular asset ended up being the worst performer”

“What if you ran that poll today? 100% for sure, Bitcoin. #2 would be stocks. Gold would probably be last.” Jared Dillian, Alpha Exchange, October 22nd, 2021

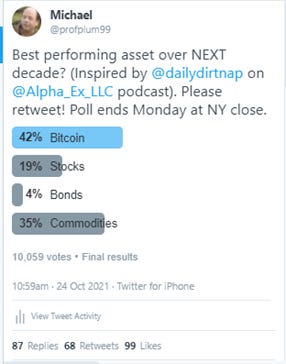

I am fortunate to have a reasonable Twitter following of ~60,000 followers, so I decided to conduct this poll. For 24 hours, I opened the following poll for answers and comments:

Unsurprisingly for a poll on Twitter, and exactly as Jared prophesied, Bitcoin emerged as the winner. The results stabilized early on and maintained a nearly constant proportion of votes over 24 hours with over 10,000 final votes. Now there are obviously limitations to a Twitter poll. Bitcoin, as a digital commodity often compared to gold, is far more popular on Twitter than in the “real” world. But I was quite surprised by the absolute dominance of Bitcoin + Commodities with 77% of the total votes. Stocks trailed quite far behind with only 19% and bonds brought up the rear with only 4% voting for currently low yielding bonds.

Now polls like these are designed to identify sentiment. As Jared highlighted, they tend to identify assets that have performed well in the recent past and are projected to perform well in the future by enthusiastic owners, but often disappoint. The popularity of a high polling asset suggests it is already broadly owned. In 2011, I will never forget an enthusiastic sell-side broker explaining to me that there were only two things he trusted anymore — “gold and gold”. A decade earlier in 2001, as I began aggressively buying gold miners for my small cap value fund, a sell-side analyst informed me, “Gold will never be allowed to climb above $350/ounce ever again.” Both forecasts proved wide of the mark over the next decade:

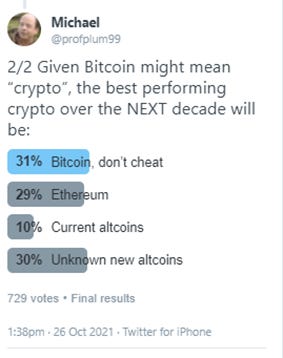

I am going to refrain from commenting on Bitcoin other than noting that the enthusiasm for the asset class and the general “anti-US dollar”/inflation trade via commodities is clear. A follow-up poll, much shorter in length but still obtaining over 700 responses indicates that the enthusiasm for Bitcoin is evenly split amongst leading crypto contenders, Bitcoin and Ethereum, with significant interest in future tokens:

A follow up question on Commodities also helps to further refine the earlier poll:

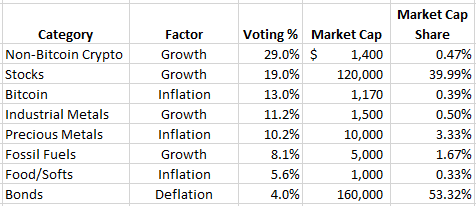

We can break down the individual components based on these refinements and end up with a table with a bit more detail. Crypto is still clearly in the lead, but as an asset class stocks do indeed show up in second place. Is it reasonable to keep Bitcoin separate? Possibly. The Bitcoin narrative is tied to different factors than Ethereum and many altcoins; instead of technology and growth, Bitcoin is a “store of value” in an inflationary environment — digital gold. And speaking of gold, instead of last place, it’s very clearly overrepresented relative to market cap.

We can broadly identify the “key factor” for most of these assets as well and the output is interesting. Aggregating the factors, we can clearly see the major disconnect between market cap and voting. Lots of deflation assets in supply, very few inflation assets despite demand:

If there is an error in this analysis, it’s assuming that non-Bitcoin Crypto is “Growth” oriented rather than inflation oriented. However, that error would simply exacerbate the underlying condition — voters are clearly more concerned about inflation than deflation and there is a significant mismatch in market cap available to bet on inflation vs deflation. With headlines from market luminaries like Paul Tudor Jones declaring Bitcoin the “best inflation hedge” (2) and that “inflation is the biggest threat to investors”, is the Twitter poll at all surprising?

Paul Tudor Jones is betting on crypto as a hedge against inflation, which he called “the single biggest threat to financial markets.”

The billionaire founder of hedge fund Tudor Investment Corp. said that he prefers digital assets over traditional hedges like gold, and has “crypto in single digits in my portfolio.” Bloomberg, Oct 20, 2021

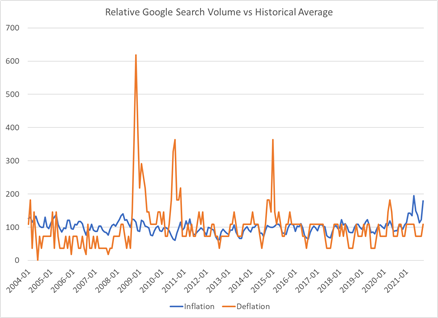

So my interpretation of the poll results is fairly straightforward — “Inflation” is the key fear and Bitcoin and Commodities are the preferred solution. This is certainly matched by Google searches. While the absolute search volume for “inflation” is always far greater than “deflation” (roughly 20x more frequent) which certainly echoes PTJ’s observation that inflation is the greatest risk (it is almost always the greatest risk), the relative search volume has clearly picked up since the Cov-19 pandemic. In contrast, the deflation spikes of 2008, 2010 (European crisis), 2015 (China related oil price crash) have retreated.

The recent increase in Google inflation search volumes is mirrored in a rise in inflation expectations as expressed through five year TIPS breakevens. Unlike prior TIPS breakeven rallies, e.g. 2009, general fears of inflation appear to have risen alongside the recovery in risk assets.

For investors, inflation is a clear concern and there is a shortage of assets to offer this protection. Assets that offer a potential solution are clearly in demand.

Will Inflation Emerge as a Sustainable Problem?

There are two competing narratives on inflation:

1) Inflation is transitory

2) A new inflationary regime has emerged

Understanding the difference is critical to any discussion. Transitory inflation is a temporary increase in the inflation rate that retreats towards the relatively stable levels of recent years. This view would suggest that a bump in the general price level associated with the Cov-19 disruptions is a permanent, but one-off increase followed by a retreat to more normal levels of inflation in the 1–2.5% range. This is clearly the consensus view of professional and public sector forecasters with expectations that the rate of inflation will retreat to 2.2% by 2023.

The second, more aggressive, scenario can be thought of as a continued high, and potentially accelerating, rate of change similar to the events of the 1960s and 1970s. Under this scenario, the inflation rate is likely to be persistently elevated and possibly accelerating. From 1965 to 1981, the five-year average rate of inflation rose from less than 2% to nearly 10%. Under the traditional narrative, this high and accelerating rate of inflation, was a byproduct of a sufficiently politicized Federal Reserve that, intent on enabling the “guns and butter” fiscal policy of the successive Johnson and Nixon administrations, failed to sufficiently rein in credit growth with interest rate policy.

This relatively benign characterization appears to have been augmented in the public discourse by the prospect of “hyperinflation” — a rapid rise in inflationary conditions consistent with the destruction of a fiat currency system. As Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey notes in a tweet apparently consistent with community guidelines for disputed or misleading information (yes, it is understood that those guidelines only apply to Covid and elections, not monetary policy):

I have very publicly challenged the theory of accelerating inflation and consider hyperinflation concerns absurd. One of the primary reasons is the fundamental misunderstanding of the unique inflationary episode of the 1970s. The common refrain for the experience of the 1970s is “stagflation” which is defined by Investopedia in the following manner:

Stagflation refers to an economy that is experiencing a simultaneous increase in inflation and stagnation of economic output.

Stagflation was first recognized during the 1970s when many developed economies experienced rapid inflation and high unemployment as a result of an oil shock.

As a challenge to this definition, I present some standard measures of economic performance — jobs created, houses built, autos sold, and change in industrial production. Any reasonable assessment of the 1970s does not reflect “stagnation of economic output.”

Why did we get high inflation in the 1970s? Because of a sustained outward shift in aggregate demand driven by the arrival of Baby Boomers, women and minorities in the labor force. Young people enter the labor force in order to increase their consumption; their initial contribution in terms of productivity is low (as any employer can confirm). This is magnified when they are provided access to unsecured credit lines, like the innovation of credit cards in the 1970s. The 1970s represented a perfect storm of demographic pressures, interest rate insensitive financial innovation (credit cards), supply constraints due to fossil fuel shortages (roughly 30% of US manufacturing capacity relied on oil power in 1970 and became uneconomic with the oil embargo), and poor interest rate policy. Faced with fundamental demand due to demographics, the worst possible strategy to managing the economy was to hike interest rates and slow capital formation; but that is indeed what we did.

Unfortunately, this fundamental misunderstanding of the 1970s inflation as a byproduct of too loose monetary policy has left us with continuing fears of a repeat when monetary policy is viewed as aggressive even though the underlying fundamentals bear no resemblance to the 1960s and 1970s. Fears of stagflation are certainly not unique this time around. In response to the surge in commodity prices from 2007 to 2008, stagflationary fears (proxied by Google searches) peaked in early 2008 despite a collapsing US housing market. Rather than predictive, these elevated expectations reflected contemporary commodity markets and an excitable news cycle. It is my belief that we are here again.

The key risk is not that the Fed does not tighten, but instead that we fail to make the investments in production and logistics (including energy) that will ultimately increase supply. Even without those investments, the lack of “real” growth in the economy is likely to restrain inflation to levels well below a 1970s experience. We are already seeing signs that the recent rise in home prices may have been driven by misdirected corporate capital rather than true demand(3):

The Argument for the Underdog — Bonds

In the face of elevated inflation, supply disruptions and shortages, record money “printing” and low interest rates, who could possibly make a case for bonds? As the poll suggests — “nobody”! But importantly, the poll also suggests nobody owns them. Could there be a reason to own them despite the optically unattractive level of yields? I believe there is.

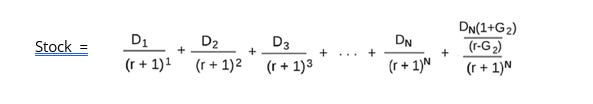

First, high-quality bonds play a unique role in portfolio construction due to their unique payoff profile. All other assets have a payoff profile that has maximum uncertainty at terminal value. We often forget this because we tend to model certainty for terminal values in the classic dividend discount model. While it appears intimidating, the important point to note is that ALL of these numbers are deterministic.

In contrast, the actual price for a stock is most uncertain at the terminal value. You may have a reasonable forecast for the level of dividends, the level of interest rates, etc., but anyone who believes they have clarity around the market’s expectation of those levels in the future is seriously delusional. Instead, the “proper” way to think of a risk asset, e.g. equities, is with a widening cone of possibilities. In the case of equities, this value is limited to zero on the downside; but for commodities and derivatives, these values can go negative as we saw with crude oil in April 2020. The bond payoff profile is distinctly different, offering certainty of nominal payoff at maturity. While this may sound uninspiring given the current focus on inflation, it cannot be overemphasized how important a role this plays in portfolio construction. For those attempting to match future liabilities with assets, the value of this certainty is mandatory and not just at the level of pension plans or insurance policies. Imagine a retiring homeowner who wants to secure their housing for an extended retirement. Paying off a mortgage is simply buying a bond.

While we often discuss assets other than bonds in terms of their “duration” (a measure of interest rate sensitivity), this is an error. Duration presumes a known terminal value. It is somewhat forgivable to discuss “effective duration” on credit instruments where the terminal value distribution is bimodal (par if no default, unknown if default), but it is a cardinal sin in equities or commodities where we have no idea of the terminal value.

The result is that there will always be demand for bonds if they remain risk-free in nominal terms.

Growing Demand for Bonds Over Time

In fact, we can comfortably assert that the demand for bonds is likely to grow significantly as the population ages. How can we be comfortable in this assertion? Because Vanguard tells us so. The “glide path” of Target Date Funds is going to become increasingly important as Baby Boomers enter retirement and Millennials mature. Designed to mimic the sophisticated advice of a retirement advisor, Target Date Funds have become by far the most common choice within the $7.3T 401K market; Vanguard estimates that 80% of all 401K accounts by number now hold a Target Date Fund4. Importantly, though, this high level of penetration conceals an important demographic disconnect. Target Date Funds are primarily held by investors under the age of 40, while the assets largely reside with older 401K investors. While representing nearly 80% of accounts, Target Date Fund assets of $2.8T represent only 35% of the $7.8T 401k market. As the first Millenials turn forty, we should expect marginal assets to increasingly flow to bonds. Using the Vanguard glide path below, this would suggest that bonds will be increasingly bid. From the age of forty to the age of 72, a typical Target Date Fund will lower equity exposure from 90% to 30%. It will be difficult to accomplish this portfolio re-orientation without selling equities and buying bonds. So who will buy the bonds? Most likely, you (or your children) will.

End notes

1. Lana Conforti, “The first 50 years of the Producer Price Index: setting inflation expectations for today,” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 2016, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2016.25

3. https://gizmodo.com/zillow-quits-home-flipping-business-laying-off-25-of-1847985910