It Really Is a Wonderful Life

More on oil demand and thoughts on heroism & modern banking

Welcome to the second episode of “Yes, I give a FIG.” This is the first post sent to all of my email recipients. If you do not want to receive the communication, please, PLEASE unsubscribe. The last thing either of us wants is more email pollution. Have to save the trees.

Last week’s piece was a lot of fun to write, slightly less fun to defend against outraged oil bulls, and ultimately quite helpful in establishing where consensus sits and identifying some areas where bulls and bears might disagree.

There were three main criticisms:

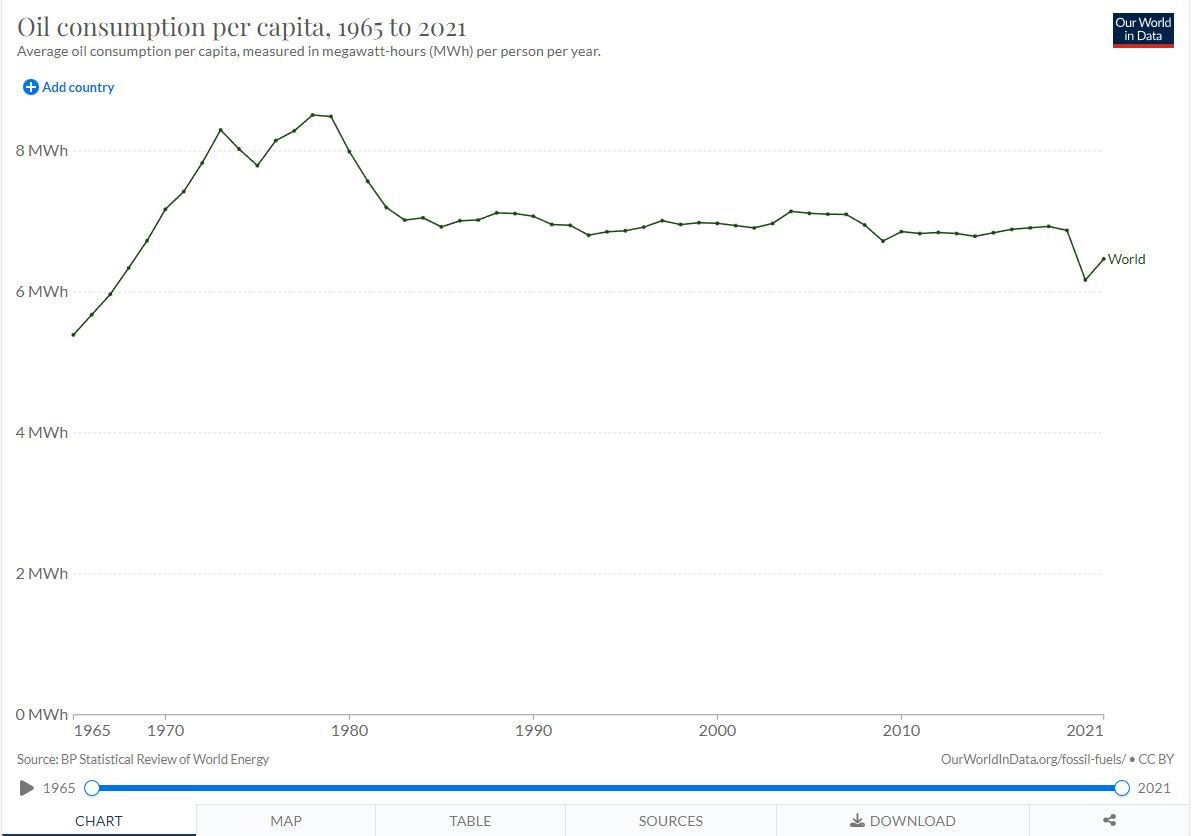

A disagreement on OECD pattern of declining oil usage per capita

A criticism of per capita approach as it fails to consider shifts in sectors within countries

Concern that the approach failed to consider rising wealth in Emerging Markets

These are all worth considering. The area I am most comfortable defending is the declining pattern of use by OECD as there we are seeing a combination of rising fuel efficiency in automobiles (CAFE standards in the US will more than double fleet fuel efficiency by 2035 given current replacement rates), fuel substitution (Ford anticipates EV capacity at 600,000 vehicles in 2023 versus total sales of 1.9MM units in 2022), and increased real oil prices which will lower aggregate demand in the future. Remember, I am not arguing that oil prices must crash; I am arguing that fears of a super-spike to $200+ (or even $100+) are self-defeating for exactly these reasons.

I don't have much to add to the criticism of a per capita approach versus sector shifts. It’s a sophisticated argument largely embedded within the per capita use/unit of GDP. Still, I have not invested the time and effort to break down the oil usage per unit of GDP per sector. Part of the reason is that I do not believe these metrics are stationary. Rising oil prices encourage innovation and conservation in all use sectors, and breakthroughs, e.g., electric & hybrid vehicles in passenger cars, are often applicable to other sectors, e.g., mining trucks. I’m certainly open to pushback here.

On the “rising wealth” in EM, I am certainly open to pushback, but there are a number of dynamics that I believe were not considered in the criticism shared with me:

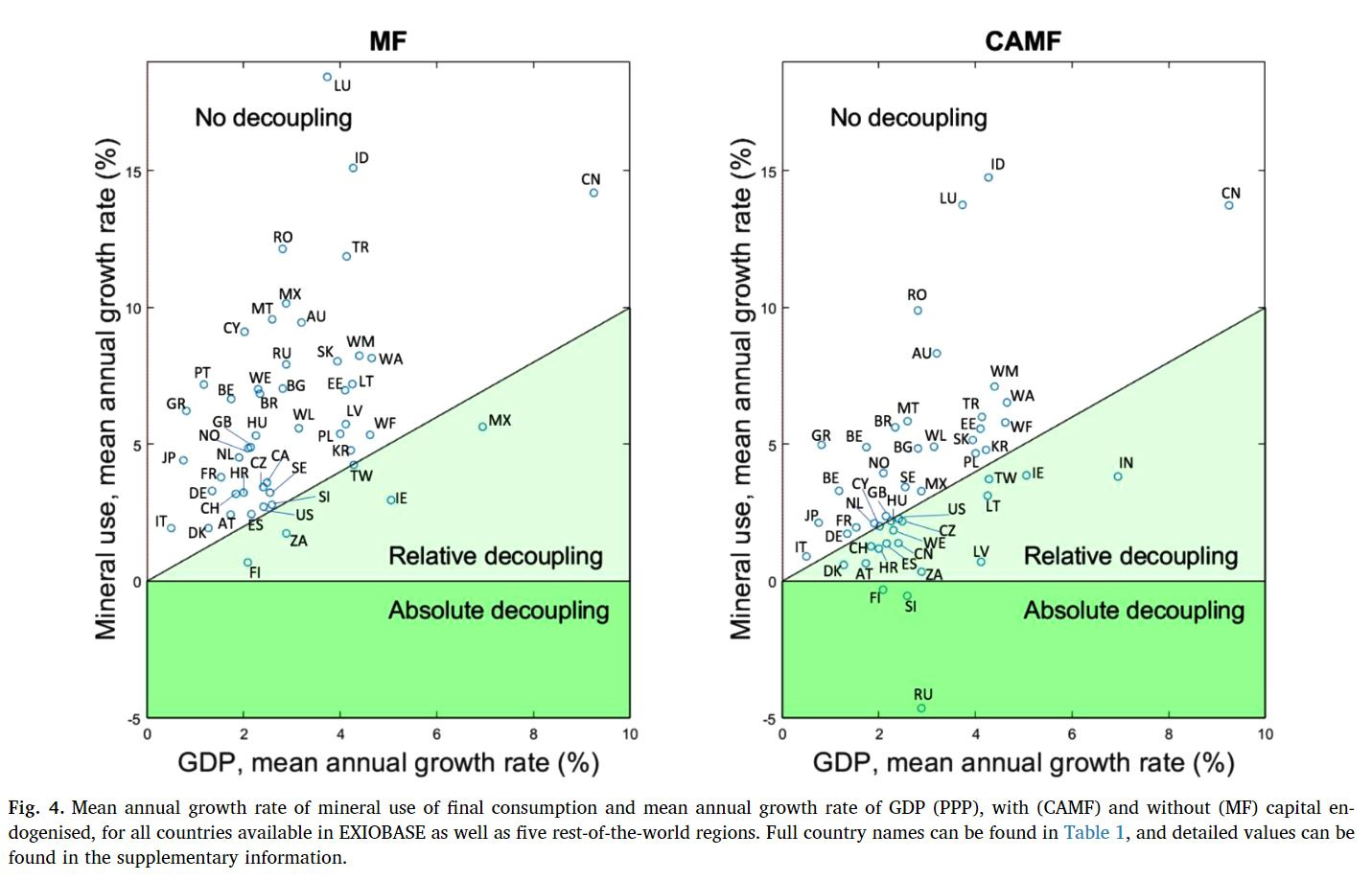

Separation between capital investment and consumption: as many market commentators have noted, switching from China to India requires India to make capital investment that is oil intensive. However, that capital investment is a “one-off” investment that pulls forward demand and does not repeat in the forward looking material footprint. In a 2020 paper, “The Capital Load of Global Material Footprints”, authors Soderstern, Wood and Wiedmann note that the “Capital Augmented Material Footprint” shows much clearer evidence of “decoupling” in GDP. In other words, once we adjust for the 1x capital investment, materials and energy usage grow much more slowly than aggregate GDP for most countries. Notable outliers? China. This suggests that China is somewhat uniquely inefficient in its material usage and is one of the reasons why I applaud the shifting of production away from China.

The underlying limits to absolute oil intensity of use are not simply a function of GDP per Capita, but also tied to factors like population density and technological innovation. A great example of this can be generated by running coefficients of oil demand per capita for China and India using GDP/Capita (constant US$), population density and year. At current GDP/Capita of ~$1,800, India compares to China in 1998. And India’s higher population density (urbanization) currently supports even more oil consumption per capita vs GDP/Capita than China at a current rate of development. However, demand for personal transportation declines as a function of GDP beyond a certain level AND as a function of population density. This can be seen in a chart of GDP per Capita vs Autos per Capita:

Up to about $20,000 US (real 2000), vehicle demand rises rapidly. Beyond that level, it plateaus with urbanization being a meaningfully negative impact to final demand. If the story were rising GDP/Capita (which does indeed have a positive correlation to oil demand), we’d never see flat to falling oil consumption per capita despite rising GDP/Capita on a global basis:

With that said, up to this point India has very much followed the China path on oil/capita vs GDP/capita, so I may be wrong. But I remain skeptical.

.And while skeptical, I am certainly open to feedback.

Moving forward, this week I conducted a Twitter poll on the movie, “It’s A Wonderful Life”:

One respondent noted:

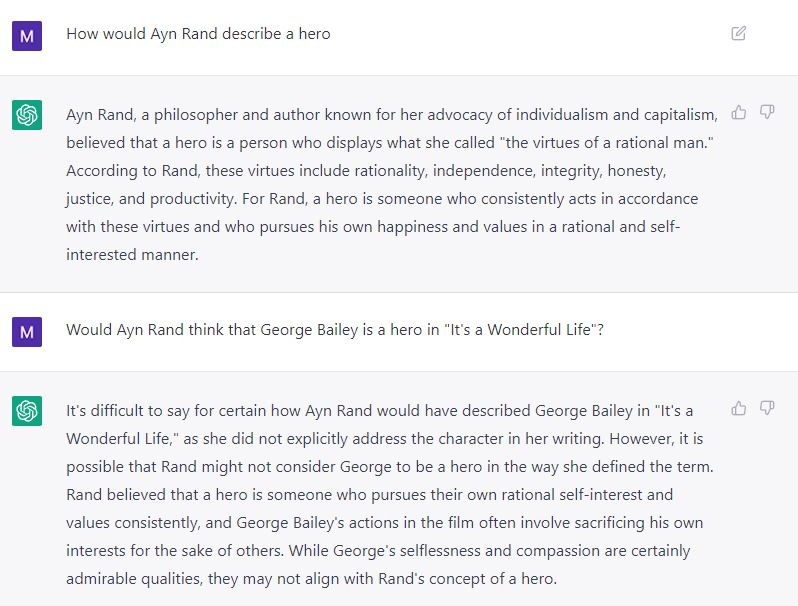

When presented to ChatGPT, the AI concurs:

And yet, an Objectivist might disagree… strongly:

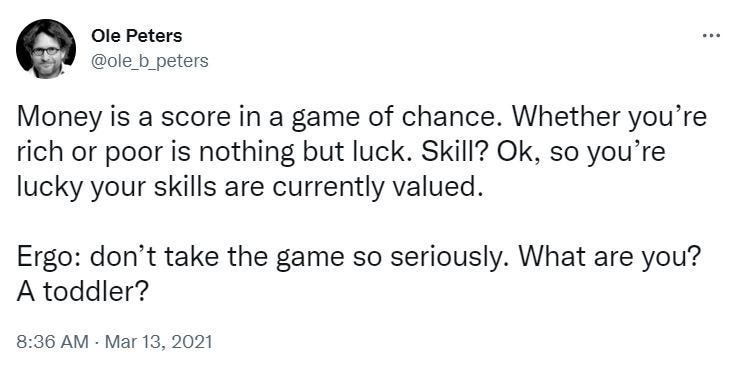

In many ways, I believe this contrast defines many of the challenges we are currently encountering in our society. The Libertarian ethos of “Just leave me alone to pursue my self-interest” has unquestionably become the dominant perspective in financial markets. It is presumed that the government that governs least, governs best. And yet I would direct my readers to the work of Ole Peters:

Ole’s work focuses on the difference between time-averages and ensemble averages. The easiest example of the difference is by looking at the rolling of dice. If I roll two six-sided die 1,000x, my distribution is going to look almost identical to the distribution of 1,000 people rolling two six-sided die simultaneously. I ran the numbers so you don’t have to:

The distribution of dice rolls is “ergodic” — the ensemble average (1,000 people rolling once) is the same as the time series average. While in this example there are very modest differences, the point is fairly clearly made:

In contrast, if I were to ask the same question about one person investing for 55 years (typical investment horizon of 40 working years and 15 years of retirement) and 55 people investing for one year, it is painfully clear that these will not produce either the same average or the same standard deviation. And this is where “luck” begins to play an uncomfortable role. Did Warren Buffett invest brilliantly? Absolutely. Would he have survived to invest brilliantly had he contracted malaria as a young child? Unknowable. Would he have become a brilliant investor had his father not encouraged his interest or offered him his first job after college? Unknowable.

But we know that in the game of compounding with ANY degree of luck, early success matters. It’s why Mark Cuban can laugh about being wiped out in his investment in crypto token Titan, when it turned out to be worthless. He made his fortune cashing out of a similarly worthless business (Broadcast.com) to a nearly worthless business (Yahoo) at the right time.

Ole has a fascinating hypothesis — perhaps the distribution of wealth in our society has far less to do with merit than luck. And he brings the data to back it. I encourage everyone to read his blogpost on redistribution and interest rates.

In the simplest terms, redistribution through taxing “lottery” like winnings is an important component in not only keeping a system “fair”, it actually improves aggregate outcomes. And yet in our modern society we are told that success is a function of merit. The historical parallels to previous “dark” episodes in humanity were laid bare for me in reading the new book, “Free Market” by Jacob Soll. In general, periods, where the working poor were protected and granted low taxes (encouraging accumulation) and the investing rich taxed (encouraging redistribution), economies flourished.

I would be very open to readers’ thoughts on this subject. Still, I can’t shake the feeling that our flirtation with Ayn Rand and unfettered “capitalism” (if we can call voracious lobbying of Rome, “capitalism”) is increasingly the cause of our malaise. Perhaps, like George Bailey, we need to go back in time and look at our choices differently. The community may indeed emerge the hero.

That’s enough for this week. Thank you for any feedback.

The second half is tremendous. Many with the classic "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" mentality haven't imagined being born in the south side of Chicago.....or Djibouti, Africa.

The Bible does elucidate a similar point,

Ecclesiastes 9:11 NKJV

I returned and saw under the sun that— The race is not to the swift, Nor the battle to the strong, Nor bread to the wise, Nor riches to men of understanding, Nor favor to men of skill; But time and chance happen to them all.