How Can You Measure?

What gets measured gets managed... sometimes disastrously

Quick housekeeping note: at 6pm PST tonight (January 22nd, 2023) I will be hosting a Zoom call with Richard Duncan to discuss his book “The Money Revolution: How to Finance the Next American Century” The link for the Zoom can be found here. The passcode is 644959. If you cannot attend, please do not fret. First, it’s probably boring. Secondly, a replay will be distributed on Twitter and placed on this site. Assuming this is enjoyable, expect regular “Book Club” discussions.

Now back to regularly scheduled programming.

The expression, “What gets measured, gets managed” is often misattributed to legendary management guru, Peter Drucker. It originates from far less famous V.F. Ridgway in a 1956 article “Dysfunctional Consequences of Performance Measurements.” It is not, as is commonly misinterpreted, an encouragement to expand quantitative measurement techniques. In fact, quite the opposite:

“Judicious use of a tool requires awareness of possible side effects and reactions. Otherwise, indiscriminate use may result in side effects and reactions outweighing the benefits (…) The cure is sometimes worse than the disease,” V.F. Ridgway

I’ve been ruminating on this topic. Let’s be clear, measuring is not the actual issue. The importance of measuring properly cannot be overstated and is the reason why every major government has a “Division of Weights & Measures” that ensures the rulers are properly measured. 12 inches (304.8mm) for every foot-long hot dog is critical to maintaining order in a polite society. So is enforcing that toilets only use 1.6 gallons per flush. Perhaps a bit tongue-in-cheek. But it is, in fact, quite critical that the small electrical appliance you purchased does indeed run on 120V systems or that the US Gold Eagle coin you accepted had 0.999 fineness and gold content of 1oz. James Vincent’s fascinating book “Beyond Measure: The Hidden History of Measurement from Cubits to Quantum Constants” is a great read on this topic.

But the unintended consequences of “kind of” measuring can be severe. What do we make worse by measuring? Well, how about economics? The helpful website, usgovernmentspending.com, defines the US budget like this:

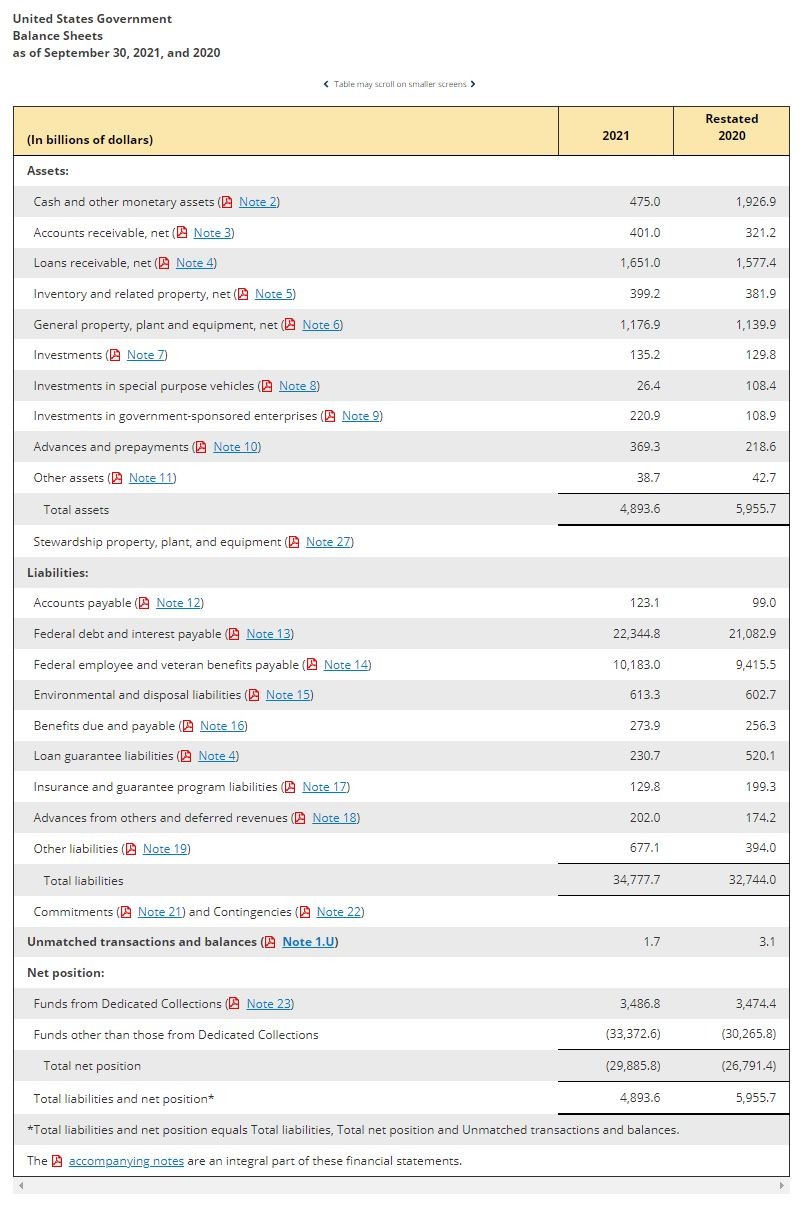

Many of my readers likely have passable accounting knowledge and will be well aware that this is a terrible way to present a budget. There is no capital account, no measure of assets in a meaningful sense, no measure of future value, etc. The entire information is “How much are we spending above our current revenue collections, and how much did we spend above our historical collections?” Even if we expand the financial statements to the official “balance sheet” courtesy of the US Treasury, we’re left with little additional information:

Now we’re all drawn with a sense of horror to the “total net position” of negative $29.885 trillion (the “debt”), but skim over the misrepresentation of “stewardship property, plant and equipment” as zero value. What is “stewardship”?

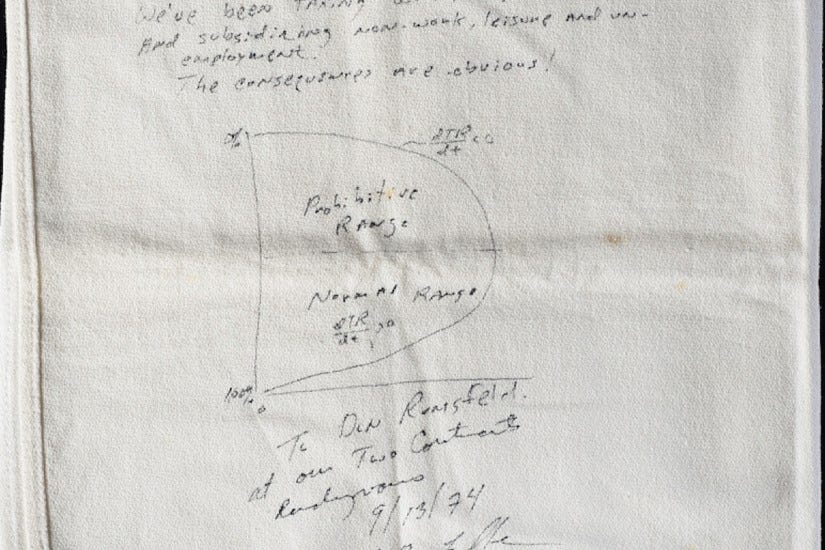

Stewardship PP&E consists of items whose physical properties resemble those of general PP&E traditionally capitalized in financial statements. However, stewardship PP&E differs from general PP&E in that their values may be indeterminable or may have little meaning (for example, museum collections, monuments, assets acquired in the formation of the nation) or that allocating the cost of such assets to accounting periods that benefit from the ownership of such assets is meaningless. Stewardship PP&E includes stewardship land (land not acquired for or in connection with general PP&E) and heritage assets (for example, federal monuments and memorials and historically or culturally significant property). The majority of stewardship land was acquired by the government during the first century of the nation’s existence.

Oh… that stuff:

How do we value that? We don’t. We measure tax revenue, and we measure spending, but we have no metrics to measure our “stewardship.” The dictionary defines stewardship as “taking care:”

To me, at least, we’ve identified a big piece of the “problem” in the world today. We’re MISMEASURING what matters. The “proper” (I am adding air quotes to indicate I am more than aware that many, including me, may find the actions of the US government and citizens reprehensible at times both current and past) stewardship of these lands allowed us to attract the real assets of the United States — humans. Try to ignore the political posturing in the early parts of the below video and instead revel in the liberation of human talent created by the development of that “land acquired by the government in the first century of the nation’s existence”:

Nowhere in the system of national accounting does it indicate that the United States has net attracted 72 million people since its founding. In insurance terms, a human life in the United States is valued between $1-10MM in current dollars, or between $72 and $720 TRILLION that completely fails to show up on the balance sheet. The total population of the US, the “subjects of the crown”, would be worth ~$3.2 QUADRILLION at the upper end of the range. Where’s that being measured?

Sweden, on the other hand, lost nearly 20% of its population to emigration over the same period, and no one seems to have changed the system of national accounting for Sweden to reflect Sweden switching from emigration to immigration around 1940:

None other than Charles Kindelberger, of “Manias Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises” fame, wrote on Sweden of the 19th century as “antiquated” in its financial system and the generally acknowledged impetus for Sweden’s rapid economic advancement starting in the late 19th century was growing competition to retain the existing workers by investing in capital improvements that raised productivity and output per (remaining) worker. As noted in another academic paper, focused on the changing role of women in Swedish society, captures the evolution well:

“The second half of the nineteenth century was a period of transformation encompassing several aspects of Swedish society. The change included the economic and financial structure of the country, as well as the legal framework and the labour market. The research proves that unmarried women's wealth increased in the period here analysed, even though dissimilarly between spinsters and widows. Their wealth changed also from a qualitative point of view, as shown by the increasing presence of specific assets such as real estate and stocks recorded in their inventories. Among the several factors that can be retraced at the origins of this phenomenon, the development of a more equal legal framework and the evolution of the housing market seemed to have played a major role.” Pompermaier, 2021

What was Sweden forced to recognize that the US currently does not? We must compete not to balance our current “books” but to raise the value of our assets net of the costs incurred to do so. A capital budgeting method that properly values human capital and underdeveloped resources under our “stewardship” is critical. Our methods of measurement are driving our current malaise.

Imagine a state of the union focused on the revenue generation, development potential, and debt retirement benefit of human capital growth. Oh, wait… the first written State of the Union emphasized exactly that:

“I lay before you the result of the census lately taken of our inhabitants, to a conformity with which we are now to reduce the ensuing ration of representation and taxation. You will perceive that the increase of numbers during the last 10 years, proceeding in geometric ratio, promises a duplication in little more than 22 years. We contemplate this rapid growth and the prospect it holds up to us, not with a view to the injuries it may enable us to do others in some future day, but to the settlement of the extensive country still remaining vacant within our limits to the multiplication of men susceptible of happiness, educated in the love of order, habituated to self-government, and valuing its blessings above all price.” — Thomas Jefferson, 1800

We have been slowing in growth in real GDP/Capita ever since we abandoned territorial acquisition (yes, I know Iraq, etc can be debated) and the general malaise we are experiencing is almost identical to the cycle that ended with the Great Depression:

Now there are two possible interpretations of the above chart. The first is the Robert Gordon interpretation — that’s as good as it gets and prepare for the inevitable pain. Or there’s the Michael Green interpretation — “Surplus creates more surplus.”

Peter Thiel famously asks: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”

Now my answer in 2016 when I first began working with him was “Passive investing is changing market structure.” I’m sure I’ll return to that subject in some future note. But if you were to ask me today, that answer would be:

“That the future is (potentially) so bright we have to wear shades, but we’re terrified to take the risks that will make it happen.”

The force multipliers that enabled the rapid growth in the late 19th century were not just “more people” or more land. As brilliantly articulated in the Solow Growth Model of accounting, output is a function of Labor (L) and Capital (K) with a smattering of technology (A):

Y* = f(L,K) = ALαK 1-α

Importantly, in this model technology “A” is labor augmenting which is consistent with empirical data. So how can we grow incomes (Y*)? Aggregate incomes can grow by adding labor, but per capita incomes can only grow by adding capital and/or augmenting labor. It stands to reason that the earlier we augment that labor, the better. Can we identify if this insight is correct? Well, interestingly, we can turn to government spending programs to test this insight… and it appears largely correct that the younger the recipient, the more benefit. The more focused on “augmenting” labor, the better:

Now we can argue about the exact details of measuring “net cost” or “benefit”, but it seems quite straightforward that properly measured, some government programs are going to offer positive returns and we should absolutely be making these investments. It’s also critical to note that how we choose to finance them matters. The only positive I will accede to on the Fed’s interest rate hiking folly is that it will likely force a discussion on this topic.

Most readers will be familiar with the concept of diminishing returns. Charts like the one below on debt & growth are all too familiar:

And this is the second area of clear insight — even the “best” policies have diminishing returns. The famous Laffer Curve is simply the above chart turned on its side:

And at one point, it was true that taxes were simply too damn high. But look what’s happened since the critical 1981 tax reform — with a modest retreat in scale in 1986, each successive tax plan has had higher costs and lower benefits:

Graphically, this seems fairly obvious as, other than the inflection in 1981, effective tax rates have continued to rise for households (largely composed of the middle class) while falling sharply for corporations (a proxy for effective tax rates on the wealthy):

Unfortunately, this evidence is backed up by empirical tests of the Laffer Curve. An analysis of the impact on corporate tax policy on liquor sales in Pennsylvania, an interesting test case market because of its highly regulated nature, illustrates that we’ve likely long passed the “optimal level” of tax collections both for revenue collection AND consumer welfare. Interestingly, this paper evaluates a “flat tax” — often pushed for its simplicity and “fairness” and finds that it penalizes the lower income consumer:

So here I am advocating for a very unpopular view — “Federal taxes are likely too low (and not progressive enough), especially on corporations.” I can already hear the Bitcoiners… “STATIST!!!” I’m not naive, the same State of the Union I referenced above has a clear warning:

“Considering the general tendency to multiply offices and dependencies and to increase expense to the ultimate term of burthen which the citizen can bear, it behooves us to avail ourselves of every occasion which presents itself for taking off the surcharge, that it never may be seen here that after leaving to labor the smallest portion of its earnings on which it can subsist, Government shall itself consume the whole residue of what it was instituted to guard.” Thomas Jefferson, 1800

Navigating Scylla and Charybdis is never easy. On the one hand, we have excess government spending on programs that offer little to no benefit (a similar study shows consistent OVER provisioning of elder healthcare services). At the same time, we cut programs that offer clear benefits. And we must acknowledge that it is the nature of any organization to consume what it can. However, I am encouraged that recent state government speeches (not coincidentally by another Virginian, Glenn Youngkin) are beginning to resemble the Thomas Jefferson State of the Union not by lambasting the government, but by highlighting its proper role as steward:

Making it cheaper for people and businesses to be in Virginia, Youngkin told the legislature’s money committees, will boost Virginia’s position as it competes with other states for talent and economic investment.

“We can grow our way to lower tax rates,” Youngkin said. “We can keep Virginians here, including our veterans. We can attract people from other states, and fuel the economic engine that will drive it all even faster. And we must get started now.”

I agree. Let’s get started now.

I think it helps your argument to include the consideration of tariffs in the discussion of the History of the growth of U.S. wealth over time. The 72 million were attracted by a national tax system that subsidized wages and taxed foreign capital and labor. We now have a system that taxes domestic labor and allows capital to avoid taxation by nominally living offshore.

What gets measured gets managed... and that is why the students in classrooms often leave without anything except enough points to earn the necessary/desired grade. The dreaded "Will this be on the test?" interrogative from students will ever be voiced as predictably as the sunrise. Also predictable, the avoidance by political leaders of measuring anything in a way that would be negative for their paychecks and power positions. Given that bit of venting as emotional asides, the idea that we collectively, through governmental entities, might invest in something that cannot be provided well without that collective action reminds me of Mancur Olson's work as detailed in "The Logic of Collective Action". Good book. Sometimes the market has problems providing what is required to advance the collective welfare of a community/region/nation/world. And of course, people take that bit of truth and stretch it until it becomes counterproductive. Hey, will this FIG essay stuff be on the test?