In the last year, the United States has grappled with crippling inflation that has risen to levels not seen since the early 1980s. The Federal Reserve, led by Chairman Jerome Powell, has been forced to discard the “transitory” language it originally adopted and begun a series of rate hikes to reduce both the level of current inflation and, more importantly, inflation expectations. The Chairman and other Federal Reserve Board members have indicated that interest rates must be hiked aggressively to reduce demand and eliminate resurgent inflation before it becomes entrenched. After over a decade of low interest rates, it seems the time has come to pay the piper.

Unfortunately, Fed actions fly in the face of their own analysis that indicates the inflation remains transitory. Aside from the housing speculation assisted by the Fed’s aggressive presence in mortgage financing, the other drivers of inflation are not monetary policy but rather the 2020 shutdowns, aggressive fiscal policy to offset the pandemic, which facilitated a V-shaped recovery, and the unexpected disruptions associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As Jerome Powell noted in his Congressional testimony, “There’s not anything we can do about oil prices.”

The Fed seems less willing to admit that the tools that they can deploy have a much larger impact on investment spending than on consumption. Within economics, the role of interest rates on household consumption is referred to as “intertemporal substitution” — the willingness of households to defer consumption given the prospect of earning higher real returns via rising interest rates. To quote the 1988 paper by Robert Hall, “A detailed study of data for the twentieth-century United States shows no strong evidence that the elasticity of intertemporal substitution is positive.”1 In English, interest rates have little to no effect on consumer spending.

Where the evidence is much stronger, however, is in the elasticity of investment. Here, estimates range from -1x to -2x, indicating that a 1% increase in the cost of funds results in a -1% to -2% decrease in investment2. What the US needs is investment. Investment in infrastructure to facilitate the clearing of clogged ports, investment in oil refining to lower the absurdly high utilization rates of the current operations that produce gasoline and diesel, investment in entry-level new single-family and multi-family housing to encourage household formation, and investment in domestic manufacturing to reduce dependence on increasingly hostile foreign powers like China. While many are frustrated with the Biden administration’s failure to lead, relying on monetary policy is not the solution to our current crisis.

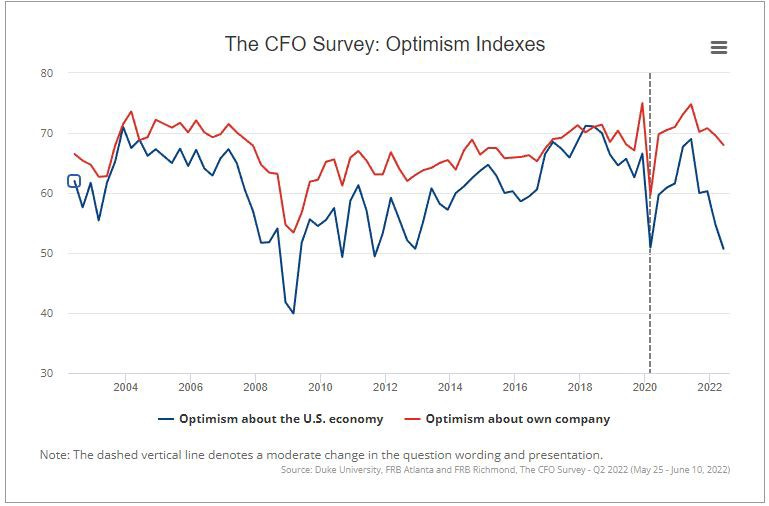

With the Fed’s newly found sobriety more than doubling the marginal cost of financing for many companies, economic theory suggests that discretionary investment will come to a standstill — an ominous forecast increasingly borne out by plummeting CFO confidence surveys which have already taken out the March 2020 pandemic low and are rapidly approaching the depths of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Surveys of consumer sentiment are already below the 2008 troughs and the University of Michigan survey of consumer sentiment recently took out its lows from the original Volcker era in 1980 — when gasoline was being rationed and unemployment hit 7.5% on its way to a pre-Covid record of 10.8%4.

Despite the well-known “long and variable lags” associated with monetary policy, the relatively minor hikes in interest rates that have occurred since the start of 2022 have managed to almost derail the US financial system completely. High yield issuance has been arrested. Mortgage rates have more than doubled in less than a year, and home buying activity is collapsing with cancellations of sales contracts for new homes rising rapidly. Despite shortages of key components, inventories of both new and used cars are beginning to increase and layoffs have begun. Frightening rumors of consumer household distress for the bottom half of households are beginning to multiply — delinquencies and defaults are rising at an alarming rate for areas as diverse as installment payments for Amazon purchases, auto loans and direct lending to small businesses. Credit card spending on necessities has exploded.

The choice that U.S. leadership, both public and private, face is the lesser of two evils. For more than two decades, we have relied on the ability to outsource our production function to China. The resultant lack of inflation pressures has allowed the Fed to use monetary policy to mitigate the impact of crisis on both investor portfolios and household employment. As the post-pandemic era makes clear, that is no longer a reasonable strategy.

But it is also not rational to deploy tools that are not fit for the purpose. The Fed is on the verge of committing a calamitous policy error. It is time for Mr. Powell to stop.

1 “Intertemporal Substitution in Consumption”, Robert E. Hall, NBER 1988

3 Bloomberg

4 BLS