American Exceptionalism

The Refinancer, The Manager, and the Missing $606 Billion

It’s a long one this time. I’m placing the paywall AFTER the social commentary, but before observations on markets. This is another piece I hope is widely read. It’s long enough without burying it in market jargon.

We invoke “American Exceptionalism” constantly without pausing to ask where the idea came from. The origin of the term is far more precise—and far less flattering—than its modern usage suggests. But there is a deeper version of the idea, one that predates the phrase by 150 years, and it begins with a man giving power away.

The First Refusal

In December 1783, George Washington performed an act of political self-denial that the 18th-century world considered a physical impossibility: he resigned. He held absolute command of the Continental Army and the implicit offer of a crown—and he walked away. In doing so, he reached back across two millennia to the Roman ideal of Cincinnatus, proving that the American experiment would be built not on the reach for power, but on the capacity to refuse it. George III reportedly said that if Washington did this, he would be “the greatest man in the world.” He did it.

This is the founding act of American Exceptionalism. Not the Declaration. Not the Constitution. A man to whom the maximum power was given chose to diminish it in favor of the people. Everything that follows in this essay—every crisis, every choice, every failure—is measured against that standard.

Stalin’s Sneer

In the late 1920s, Jay Lovestone, General Secretary of the Communist Party USA, argued that American capitalism was unusually resilient—temporarily exempt from the “universal laws” of Marxist collapse. When Lovestone defended this view in Moscow in 1929, Joseph Stalin responded with fury. He denounced the argument as a “theory of American exceptionalism,” not as praise, but as a sneer. To Stalin, America wasn’t special; it was just behind schedule. Within months, the Great Depression began, and it appeared the “universal laws” were reasserting themselves.

To understand what happened next—and why it matters for 2026—you have to understand what “money” meant to the men who ran America.

Morgan’s Hierarchy: Money vs. Credit

“Money is gold, and nothing else; all the rest is credit.” J.P. Morgan said this to Congress in 1912, and he wasn’t being poetic. He was defining a hierarchy. Bank deposits were merely a promise to pay money—they were credit. And the “Gold Clause,” a contractual legacy of the fear of Civil War Greenbacks, was the creditor’s insurance policy: all debts were repayable in gold coin at the creditor’s option.

In periods of prosperity, the ratio of credit-to-money (gold) functioned as a useful abstraction. But by 1933, the public stopped believing in the promises. They rushed to convert their “credit” into “money”—physical gold and currency. The math was a physical impossibility. The private sector was legally committed to settling $100 billion in gold-linked contracts. The total gold in private hands was approximately $1 billion.

It was a systemic margin call. And because settlement was at the creditor’s option, any government attempt to devalue the dollar would simply trigger the Gold Clause. The nominal value of the debt would have exploded to match the devaluation, wiping out every debtor in the country instantly.

Three New Deals

Confronted with this impossibility, Roosevelt surveyed a world where the classical liberal model had failed. As Wolfgang Schivelbusch outlines in The Three New Deals, the 1930s offered three distinct paths:

The Mussolini Model (The Corporate State): Enforce the creditors’ claims by force. Use the state to suppress the mob and ensure nominal financial claims remain whole.

The Hitler Model (National Socialism): Nationalize the logic of the nation. The state absorbs private property and industry into a monolithic command structure.

The Roosevelt Model (Principled Abrogation): The “Exceptional” Path. Roosevelt—in the tradition of Washington’s resignation—chose to save the private market by attacking the mathematical ghost that haunted it. He used the Pen to abrogate the Gold Clause, performing a surgical strike on the $100 billion liability.

By choosing this path, Roosevelt effectively “printed” $69 billion in equity for the nation. He saved the railroad equity, the farmer’s land, and the average citizen’s bank deposits by sacrificing the creditors’ unrealistic “option.”

This is the distinction that matters: the Refinancer changes the rules to save the system. The Manager picks winners to control it.

The Business Plot and the Black Book

The creditor class did not take the 1933 abrogation lying down. The Business Plot of 1934 was a plan by financiers — including names like Robert Sterling Clark and allegedly Prescott Bush — to overthrow FDR and replace him with a fascist military state.

The plotters approached Major General Smedley Butler, the most decorated Marine in American history. Butler was the “Refinancer” of the military; a man who had already exposed the structural rot of the defense industry in War is a Racket. He held the pedigree to lead a coup and the credibility to sell it to the rank and file. Butler refused. He went to Congress instead.

In the taxonomy of this essay, Butler was Washington’s echo: a man who held the power to become the Manager and chose constraint. Washington resigned a commission. Butler refused one. The pattern of American Exceptionalism isn’t ideological—it’s behavioral. It is the repeated choice of constraint by those to whom the maximum power was offered.

Roosevelt didn’t just survive the plot; he weaponized it. Instead of a public trial that might have sparked revolution, he worked with the McCormack-Dickstein Committee to suppress the most damning names from the final report. He kept the evidence of treason as a private file of kompromat, ensuring the elite’s subsequent obeisance. They didn’t sign on to the New Deal because they believed in it; they signed on because the President held their lives in his desk drawer.

The Epstein Model: Obeisance by Redaction

This is the historical precursor to the Epstein model of governance: a system where the state ensures elite compliance not through the rule of law, but through the possession of the “black book.” Hoover’s FBI ran the same playbook for decades. The mechanism is always the same: you will do what I tell you, or I remove the blackout.

In 2026, the Epstein Files Transparency Act was supposed to break this pattern. Instead, we are witnessing the logic of 1934 perfected. On January 30, 2026, the Department of Justice dumped 3.5 million pages of files, but the “transparency” is a facade. The DOJ has withheld nearly 200,000 pages under “privilege” and has systematically blacked out the names of public figures while “accidentally” exposing the victims.

The true “Black Book” has simply been moved to a DOJ reading room. On February 2, 2026, the administration announced that only members of Congress—the very people most susceptible to institutional leverage—would be allowed to see the unredacted names. The public gets the redacted mess; the Manager gets the leverage. When Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche stated that there was “nothing in there that allowed us to prosecute anybody,” he wasn’t declaring a lack of crime; he was declaring a refusal to act. The blackout remains the tool of the Manager. “You will do what I tell you, or I remove the blackout.”

Likewise, the investigation into Jerome Powell—a man I loathe for his intellectual incuriosity, but accept is trying his limited best—is a transparent pretext to remove a “for cause” referee and replace him with a political manager. Kevin Warsh is that man. While reshoring strategic minerals is a valid act of national security, it is being used as a license for bespoke management—dictating winners through executive deals.

Roosevelt saved the country as a Refinancer in 1933 but nearly broke it as a Manager by 1937. The “Roosevelt Recession”—triggered by premature fiscal tightening and ongoing interventionist management of industrial relations—proved that even the most skilled Refinancer becomes destructive once he starts believing he can manage outcomes indefinitely. The surgical act saved the system. The ongoing management destabilized it.

Today, we have the worst of both: a state too weak to refinance the structural imbalances and too arrogant to stop managing the chicken coop. But don’t take my word for it. Look at the numbers.

Where the State Actually Fails

The narrative machinery of the current moment—amplified by figures like Elon Musk through X’s new long-form content prizes—wants you fixated on government spending fraud. The inaugural $1 million X article award went to a piece casting Deloitte as a “$74 billion cancer metastasized across America,” alleging that taxpayer dollars were siphoned and that there were revolving doors of insiders. Runners-up included exposés on welfare fraud in Minnesota—state-level fraud, notably, not federal. The awards align neatly with Musk’s DOGE-adjacent critiques of government waste.

Here’s the irony: Musk himself faces fraud accusations ranging from misleading claims about Tesla’s Full Self-Driving capabilities to the controversial SolarCity acquisition—widely seen as a bailout for his cousins’ failing company. But the deeper irony isn’t the hypocrisy. It’s that the entire spending-fraud narrative is a distraction from where the government actually underperforms—not expense management, where it’s roughly on par with the private sector, but revenue collection, where evasion drains far more.

Private companies collect 97–99 cents on every dollar owed. The U.S. government collects 85–87 cents. That is the number that should define the fiscal debate. Everything below explains why it doesn’t.

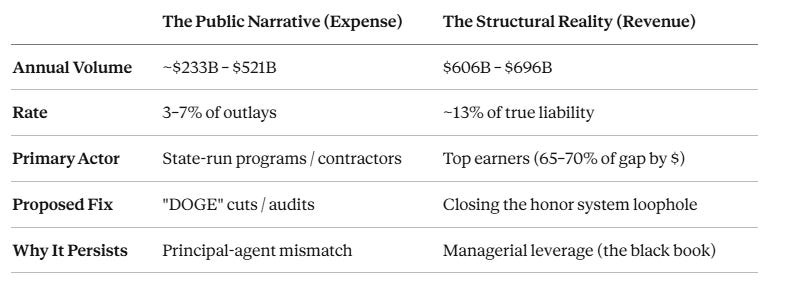

On the expense side, the federal government loses an estimated 3–7% of its ~$7 trillion in annual outlays to genuine spending fraud—roughly $233–521 billion per year (per GAO estimates isolating willful misrepresentation from documentation errors where payment was substantively proper). That range is mediocre, not catastrophic—and much of it persists due to a principal-agent problem baked into cooperative federalism. States run programs such as Medicaid with federal funds under matching formulas, in which the federal share ranges from 50–90%, thereby diluting the incentive to enforce aggressively. It’s not their money, it’s yours. This is why high-profile cases, such as Minnesota’s Medicaid schemes, arise at the state level.

The private sector, by comparison, loses 1–5% of its ~$45–50 trillion in gross output to occupational fraud and theft, per the ACFE’s 2024 global survey. Government is worse on expenses, but not by the order of magnitude the headlines suggest.

On the revenue side, the picture is devastating. The IRS projects a net tax gap of $606 billion for tax year 2022—roughly 13% of the $4.7 trillion in true tax liability. Two leading government economists disagree about where the worst abuses of that gap live: Guyton (IRS) uses detection-controlled estimation to capture sophisticated evasion that random audits miss—offshore accounts, pass-throughs, complex partnerships—and finds evasion rates rising sharply with income, with the top 1% driving roughly 30% of the gap. Splinter (Joint Committee on Taxation) argues those multipliers overstate true fraud, conflating gray-area documentation issues with willful evasion—the same measurement critique we correctly apply to spending-side “improper payment” figures. Even under Splinter’s more generous methodology, 65–70% of the gap in dollar terms still concentrates at the top. The debate is about the slope of the evasion curve, not its center of mass.

The Fiscal Mirror: The Spend vs. The Collect

The current narrative focuses on the 3–7% expense-side fraud because it suggests the state is a bumbling thief. We must reduce its power! It ignores the 13% revenue-side gap because doing so would reveal that the state is a selective partner.

The Mussolini Model in Fiscal Form

This is where the fiscal data meets the political philosophy. A genuine Refinancer would attack the revenue side, because that’s where the structural failure actually lives. Closing even one-third of the true intentional tax gap would generate more new revenue than almost any realistic spending cut.

But a Manager doesn’t want to fix the revenue side. The revenue gap is the patronage system.

The ability to selectively enforce tax obligations is itself a form of the black book. You collect from those who don’t comply politically; you look away from those who do. Musk's amplification of the Deloitte story on X constitutes the active construction of the managerial frame—the NRA Blue Eagle of 2026, a symbol of compliance. By awarding prizes for exposés on spending, the Manager ensures the public never asks why the most “Exceptional” citizens are the ones least likely to pay the entry fee for the Republic. It tells the public: your problem is that the government spends too much. It never asks: why does the government collect so little from the people who owe the most?

This is the Mussolini model in fiscal form: not the enforcement of rules, but the management of outcomes. The state doesn’t fix the tax code; it uses the broken tax code as leverage.

The Exceptional Path

Exceptionalism was never about American superiority. It was the willingness of a traitor to his class to accept constraint in order to preserve the system. Roosevelt’s genius in 1933 wasn’t that he was powerful—it was that he used power surgically and then stopped. The Refinancer says: I will change this rule, and then the market will sort itself out. Gerald Corrigan in 1987. The Manager says: I will sort it out myself, permanently. Ben Bernanke in 2008. One requires faith in the system. The other requires faith in the manager.

Today, we are fulfilling Stalin’s prophecy—not by collapsing under Marxist laws, but by choosing the corporate state, where the executive manages outcomes rather than enforces rules, and where the public is kept focused on the 3–7% expense-side problem so they never notice the 13% revenue-side catastrophe.

So the questions for 2026 are the same ones that have defined every genuine crisis in this republic: who is the traitor to his class? Who will accept power and then relinquish it in favor of the people? Washington resigned a commission. Butler refused a coup. Roosevelt abrogated a claim, but needed death to be stopped. Our luck is fading, as we acknowledged with the 22nd and 25th amendments. The Exceptional Path requires someone to whom the maximum power was given to choose to diminish it in favor of the people. We used to believe they would do it from civic duty. We were lulled into complacency by Washington.

Is the current candidate the person firing the Federal Reserve chair? Is it the tech billionaire awarding prizes for spending-fraud exposés while his own regulatory history fills a docket? Or is it someone we haven’t met yet—someone willing to enforce the 97–99% collection rate that the private sector considers standard, hold the narrators to the same arithmetic as the narrated, and then accept the constraint of stopping?

I don’t know. But don’t let the headlines distract you. That’s the point.

Section End

Markets In Space!

Well, let’s see how the year is going?

Bitcoin? Pffthhh… and largely for the reasons I hypothesized — ETF selling